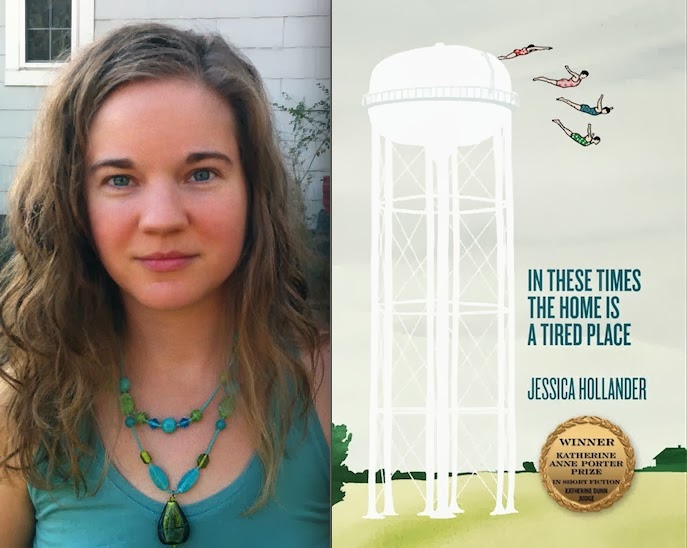

An Interview with Jessica Hollander, Author of IN THESE TIMES THE HOME IS A TIRED PLACE

Jessica Hollander is the recipient of the 2013 Katherine Anne Porter Prize for Short Fiction.

Interview by THEODORA ZIOLKOWSKI

Jessica Hollander’s debut collection In These Times the Home Is a Tired Place draws us into the lives of mothers, wives, and daughters, as well as the husbands, lovers, and others who infiltrate one another’s psychological and domestic spaces.

These stories allow us to experience the characters’ acknowledgement of and resistance to existing in a world that is anything but simple. Hollander pushes her characters into a hyper-realistic space that is constantly filled with surprises: her female leads may not initially always know how to navigate their desires, but the fervor and inventiveness of their ambition compel us to believe that they will. Through stunningly crisp dialogue and settings that feel at once familiar and surreal, Hollander has created a memorable collection that is as rich as it is moving.

BLACK WARRIOR REVIEW: Many of the stories in your collection take place in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where you grew up. The word, ‘place,’ is even included in the title. How does place influence you in your writing?

Jessica Hollander: It’s probably part my family and part the Midwest culture I grew up in to believe that suffering makes you stronger. This is something people in Michigan tell themselves when it’s freezing outside and they have to motivate themselves to dig their car tires out from three feet of snow and ice, and again when it’s April and the temp hasn’t cracked 45, and when the weather turns in September and they know there’s pretty much no end to the gray cold. I think this attitude, which to me feels so tied to my birthplace, has influenced even the tone of my writing, with the pull between tragedy and comedy, with narrators or characters that are aware and even self-mocking of their suffering to the extent that so much anxiety, indecision, and familial/relationship upheaval happens almost exuberantly, as though suffering is something that’s craved or deemed necessary to really be living. When I think of Ann Arbor and my friends and family that still live there, this is the attitude I remember and the aura that continues to come from there for me.

BWR: How do you begin assembling a collection? Did you know the overall direction this particular collection would take, or did the process of writing these nineteen flash and short stories just culminate in a collection that spoke to the themes you were thinking about?

JH: Part of what drives me to write is the challenge of trying something I haven’t done before. I was particularly conscious of experimenting with style, structure, and language during the four or five years I wrote the stories that ended up in the collection. I wasn’t thinking about compiling them as I wrote them, but more focused on pushing myself into new territory, figuring out what stories could do and be. When I had a large body of work to sift through, I was pleased to find that despite their differences, there were a lot of connections in theme, image, and character anxieties in many of the stories. During the years I wrote them, I lived through a lot of “big” moments – marriage, pregnancy, parenthood, home-ownership – and I think writing was a way to examine my own motivations and maybe even mock myself for following such a “standard path of expectations.” I wanted these things, but then I worried that it was partly because I’d been conditioned to want them. When I decided to compile a collection, I chose my favorite stories and the ones I thought spoke most to each other, I wrote a couple more to fill out the collection, and I thought a lot about ordering and what I wanted the shape of the book to suggest thematically.

BWR: Do you have a favorite story in this collection, or was there a breakthrough in your own work you discovered while writing a particular story?

JH: My favorite story is probably “This Kind of Happiness,” which I think of as the sort of “thesis” of the collection and one that helped guide the shape and stories I included. This story is the one that most directly follows a girl pulled by a culture that both glorifies and disparages traditional domesticity, encouraging her to get married and cultivate a happy family at the same time she feels warned to stay single and avoid being tied down to anyone. Her identity’s already been corrupted in that she’s referred to as “the girlfriend” instead of being given a name, and this is something we all do as a shorthand, refer to people by titles: “my husband,” “my wife,” “my daughter,” because it’s easier than giving their names, introducing them, and describing all their likes and dislikes. But we lose or disregard individuality by calling each other by the roles we play, especially when the roles have troubling historical and cultural connotations (like “wife”). So when the unwed pregnant girlfriend in the story is pressured to get married by her boyfriend, parents, co-workers, and the entire culture around her, she senses a feverish, almost surreal, intensity emanating from them. Domestic life has been idealized to the point that our culture’s imagining of it looks like parody: a family smiling brilliantly in front of a shiny new house, radiating beauty and happiness. That family can’t even blink or the picture falls apart. It’s a beauty that can’t be trusted, but we want to believe in it. We want to believe there’s a picture we can step into and be happy.

BWR: What is your favorite part about writing?

JH: My favorite part is the moment when I sense that whatever piece I’m working on is going to come together as a story. I rarely begin a piece knowing where it’s going or even what it’s going to be about. I start with a sentence that interests me and go from there. So there’s a good deal of anxiety early on, especially when I’m working with a new form or new material, that the energy is going to die off or the characters will have nothing else to say or the central crisis or movement of the piece will never materialize. But the process of discovery is exciting, too, and probably it’s the anxiety that pushes me to the end and makes me figure out how it can work, like solving a puzzle I’ve only half created.

BWR: What advice do you have for writers?

JH: Don’t rely on external feedback about your writing. The writing world is so competitive, and everyone who is going to read and judge your work has their own aesthetic preferences and criteria, so getting rejections doesn’t say anything about the quality of the work or the interesting things it’s up to. I think it’s great to occasionally push yourself outside your comfort zone and write pieces unlike what you’ve written before. Take risks and push yourself as a writer so that your writing changes and grows and so you stay interested in what you’re doing. Getting positive feedback feels great, but engaging with the writing process is what ultimately sustains us.

BWR: Who are some of your major influences?

JH: I work mostly in hyper-realism, which is like photo-realism, where you see a work of art that looks like a photograph from far away, but when you get closer, it’s too bright, and the colors are too vivid, and you realize it’s not a photo, it’s a painting. The effect is unsettling; it’s so “real” that it borders on surreal, and you can’t trust it. In writing, hyper-realism means using exaggeration and stylization – in imagery, dialogue, and action – to turn up the intensity of “real life” enough to make the reader unsettled by what they see. The writers I’ve read who most inspired me to work in this tradition include Lorrie Moore, J.D. Salinger, Raymond Carver, Ernest Hemmingway, Anne Beattie, Frederick Barthelme, Miranda July, and Deborah Eisenberg. A lot of these writers have surprising, funny dialogue as well, but another major influence in thinking about dialogue was a play I read several years ago by Maria Irene Fornes, “Fefu and Her Friends.” The characters in this play speak haphazardly, as though they’re barely thinking through what they’re saying, or they’re in the process of trying to figure out their feelings as they’re speaking. It comes across as highly-stylized at the same time it feels honest and realistic. They’re often accidentally insightful, and it’s up to the reader to do the interpreting.

BWR: What are your current projects?

JH: I designed and taught a literary gothic writing class last semester that really inspired me to explore the tradition in my own writing. I’m now compiling a postmodern gothic collection, playing with themes about the dark desires and fears that influence our perception of gender, sexuality, family, and marriage, while still working in the hyper-real tradition, juxtaposing dark imagery and gothic tropes with comedy and exaggeration (a zombie goes on Ultimate Makeover, a vampire stalks an adulteress, a dead woman tries to make sense of her resurrection, kids confront neighborhood “demons;” and then also there’s some relationship pieces where the haunting is more subtle). Gothic literature is interested in what’s unexplainable, both inside and outside of people, and looks at impulses based in emotion and not logic. There’s hauntings from the past and monsters inside of us, battles between logic and emotion, repressing feelings that later manifest destructively, and humans being drawn to the sublime and the numinous: things that inspire both fear and awe, that remind us of our own demise, but encourage us to see beauty in sadness, death, and suffering. I’m having fun.