45.1 Feature: An Interview with Tyrese Coleman

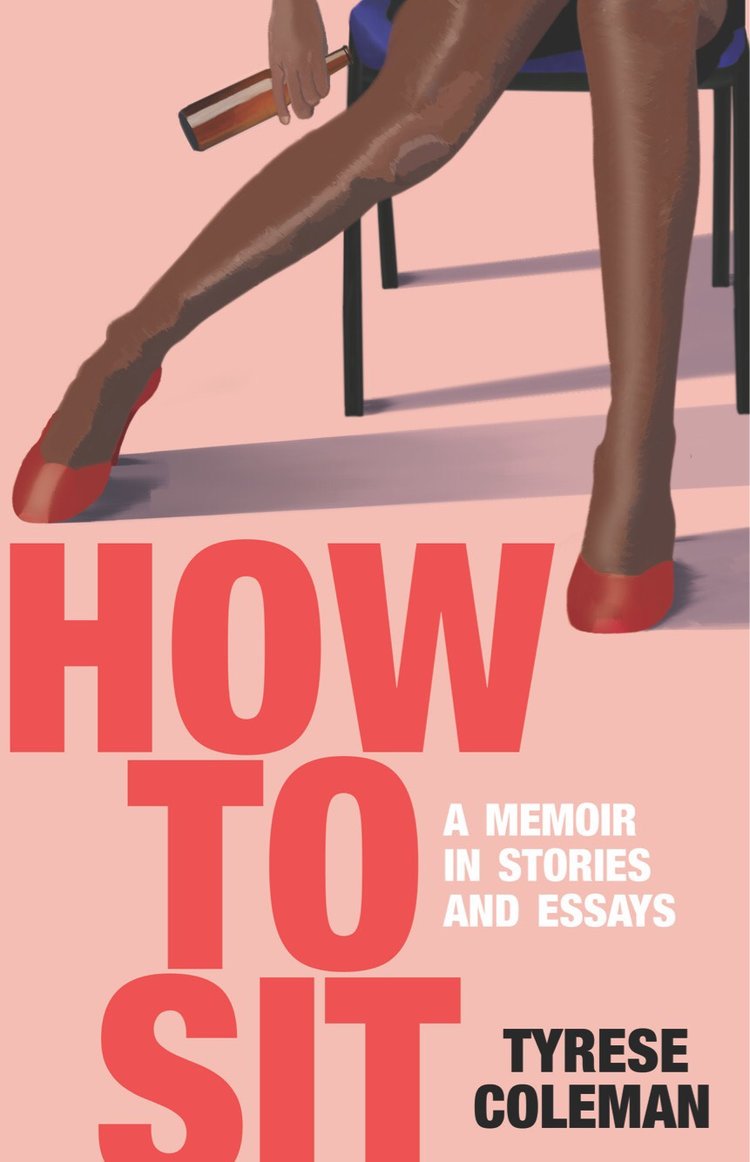

Tyrese L. Coleman is a writer, wife, mother, attorney, and writing instructor. She is also an associate editor at SmokeLong Quarterly, an online journal dedicated to flash fiction. An essayist and fiction writer, her prose has appeared in several publications, including Catapult, Buzzfeed, Literary Hub, The Rumpus, and the Kenyon Review. An alumni of the Writing Program at Johns Hopkins University and a Kimbilio Fiction Fellow, her collection, How To Sit, was published in 2018 with Mason Jar Press. She can be reached at tyresecoleman.com or on twitter @tylachelleco.

Interview by ELIZABETH THERIOT

Black Warrior Review: “Speculum” is such a gorgeous, intricately woven essay. Can you tell us the story of writing this piece? What has fed and informed you along the way?

Tyrese L Coleman: It started because of a few things that I was reading at the time.

First, the research from the UVA study on racial disparity in pain management and the treatment of black patients came out. The study showed that many doctors believed outrageously false ideas about black people, such as black people have thicker skin and therefore do not feel pain or that, because black people live “hard lives,” we are more equipped to handle pain and therefore do not feel pain as much as other races. I knew that doctors held these ideas, but I had no idea just how prevalent these beliefs were. It made me think about all the times that I had been denied access to care because I wasn’t believed or taken seriously, or, on the flip side, I shrugged off my own suffering to avoid being refused or “inconveniencing” someone with my problems. That is a real thing too: women, especially black women, not wanting to seek medical attention because of patronizing medical professionals who downplay the truth we feel in our bodies. I once had a doctor refuse to do a surgical procedure on an area of my body that caused me tremendous pain and tell me that I need to wash better. So, when you are used to being treated this way, multiple things happen to you: you resent going to the doctor, you question whether or not you are actually in as much pain as you feel, and you wonder whether or not they are right. It’s a psychological pounding down of your will to take care of yourself.

Secondly, I had heard an interview on NPR with the poet Bettina Judd about her book Patient. I read her book and also became obsessed with learning about Dr. Marion Simms and his gynecological experiments on slaves. Her book contextualizes her own medical trauma alongside the trauma of the three slaves mentioned in Simms’ autobiography. I had also just read Cutting For Stone by Abraham Verghese, where part of the plot involves physicians curing vaginal fistulas and Verghese’s descriptions of what a fistula smelled like really stayed with me.

When I sat down to write, these facts and themes were swirling in my head. I really wanted to address the feeling of impotence at the hands of medical physicians but was very nervous about writing an essay about vaginas.

BWR: This essay arrested me immediately with the omniscient, commanding, historicized voice that shares space on the page with your own: “Press your top teeth into your bottom lip,” it begins. “Say this word: fistula.” What guided your decision to address the reader directly? What do you see as the relationship between reader and writer?

TLC: I wanted the reader to witness Lucy, participate in what happens to her. It was important to me that this piece not be passive but something that readers interact with almost physically. I am hoping for squirming.

Also, specifically, I imagined my reader as a white man, and that the “you” is specifically a white man. He has inherited Simms’ legacy, which I mention at the end of the piece. To me, that legacy is too great to be ignored and white men have to participate in this too to understand what this legacy truly means. But, because this is an piece about black women, slavery and vaginas, I felt the need to educate. I’m not confident that the average white man knows anything about those topics in great depth.

BWR: As you were dreaming of and writing this piece, how did your relationship change with Lucy and your other historical subjects?

TLC: I felt that the slave women who were a part of Simms’ experiment needed to have a voice, even if it was made up. I decided that I would use one of the women he worked on and create a story for her, which is what you read about Lucy.

But, what I don’t necessarily discuss in the piece is the moral conundrum that comes from studying a man like J. Marion Simms who did terrible, horrible things to women, but who did indeed save lives and revolutionize women’s health. We will never know how much of his work was for the betterment of womenkind or the betterment of J. Marion Simms (I believe, based on his own writings, that the man was more concerned with his own fame than anything else), but regardless, there is a reason why there were so many statutes dedicated to this man. I don’t know if it’s possible to calculate the number of lives that were saved because of his treatment of vaginal fistulas. But, it’s always the same moral conundrum with men like Simms, right? One must still respect the good that came from their work despite loathing the man who did it.

BWR: I was struck, again and again, by the fish—flooding, overwhelming, demanding attention and space. Can you discuss how you came to this fabulist movement in “Speculum,” and how you see fabulist elements functioning in both your writing and the creative nonfiction genre?

TLC: I started playing around with “speculative” essay writing with a piece in my collection that appeared in The Rumpus called “Thoughts on my Ancestry.com DNA Results.” In that piece, I imagine my ancestors based on my DNA results and mix those short narratives in between accounts from my life that relate directly to my ancestry. Because I know nothing about who my ancestors were, only that I share DNA traits with people from a particular part of the world, the only thing I could do was speculate about who they were and how they got here.

That piece gave me the confidence to try out the fabulism you see in “Speculum.” I wanted the fish to represent more than just the smell of her fistula, but to also be about what was lost during the middle passage, what is lost when her baby dies, what is lost every time Simms cuts her open. The fabulist parts are meant to elevate those moments beyond the horror associated with them, to give a greater meaning, and to connect them.

I think creative nonfiction can be more than just memoir. It can be poetry. And in some cases, it can be fiction. As a writer, it is your responsibility to represent what is true and to make it clear to your reader what is not. I did that structurally by pulling out those sections and making them italics but there are other ways of doing this as well. If you do maintain that integrity, I don’t see why one cannot use fabulist elements or any other kind of element when creating nonfiction. I don’t think there has to be one way to write anything.

BWR: What are you currently reading? Which emerging voices are you most excited about?

I just read A Lucky Man by Jamel Brinkley and I am shook! It has been on my shelf for a while and I am so happy I made reading that happen. I am beyond excited to read Everyday People, which is an anthology of writers of color edited by Jennifer Baker. Looking at the table of contents of that book, you can see just how great of a literary citizen Jenn is. There are emerging writers alongside established writers in the same book and, although a lot of editors and publishers say they are for the cause and down to promote emerging writers, Jenn lives up to that with this anthology.

BWR: Please tell us about your current projects—what’s next?

My collection of essays and stories, How to Sit, was recently published so my main project is promoting my book.

However, I am currently expanding Lucy’s story. It is shaping up to be a novel, so far untitled. I have also been writing more essays about this idea of feeling impotent while being treated by medical professionals and I may transform these into an essay collection if I keep writing about it. Who knows, I might just put these two things together into one book and see what happens.