On “First Seen in Print in 1987, According to Merriam Webster”

Krys Malcolm Belc

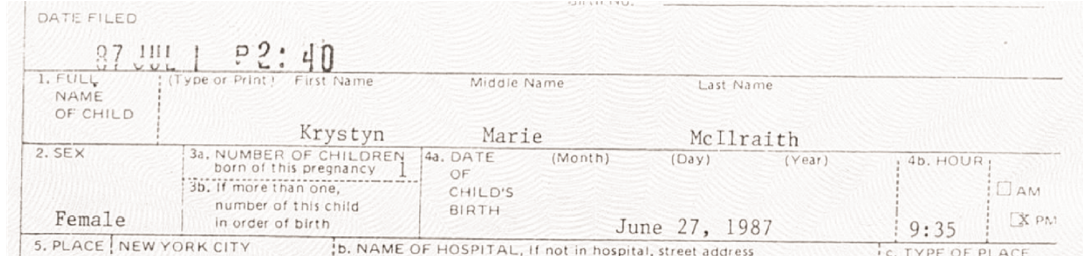

My original New York City Certificate of Birth, issued in July 1987, is a beautiful document. I love the weathered pink paper, the texture, the seal and signatures. I stare at it every time I have to go in my family’s little fireproof safe.

This paper is apparently the official record of who I was when I was born: Krystyn Marie McIlraith, born June 27, 1987 in New York City. That fact, the fact that we use documents like the birth certificate to codify who a person is, remains strange to me. I don’t live as that person; I haven’t for years. Was that ever who I was? I have revised all of my identification documents except this one. Even though that person and I have made a break, it hasn’t been a clean break. It feels strange to go back and say that I was always who I am today. The world happened to me as the person on the paper, not the person I am today, for nearly thirty years.

Writing about childhood and adolescence is a key aspect of many trans essayists’ and memoirists’ work. Jennifer Finney Boylan writes that what trans memoirs ultimately model is the “process of creating the best draft of the self.” Often, they’re redemption stories. I find them addictive to read, but I often feel an alienation from the break the writers make with their childhood selves. As a writer I’ve always looked to find a way to integrate that solemn child with the person I’ve become. If Krys Malcolm Belc is really just a new draft, the draft I present to strangers when I want to fly on an airplane or renew my driver’s license or buy a beer, do I need to get rid of the old draft? Or can it be repurposed through writing, used to bring to light new things about who I am?

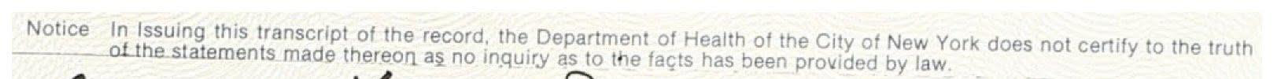

I feel in many ways that the disclaimer printed on my birth certificate means that it is meant to stay the imperfect record of my personhood that it is:

The slipperiness of this disclaimer reminds me of the slipperiness of writing personal essays, especially those about the distant past. Before I started writing essays inspired by my birth certificate, I wrote mostly about the present or near-past, rarely leaving my adult life when mining my memory. As far as my work was concerned, my life began around the same time I began moving away from being the person identified on this birth certificate. I had been born on the page fully-formed, a young adult with little past.

I have often blamed this tendency to avoid writing about anything before adulthood on a “bad memory,” but in fact my aversion is that it’s disconcerting, looking back and not recognizing the person in all my memories. I don’t feel integrated with that person. There’s a moment in W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz in which the title character, recalling events from his childhood after decades of suppression, talks to the narrator about the experience of allowing himself to examine the past. “It does not seem to me, Austerlitz added, that we understand the laws governing the return of the past, but I feel more and more as if time did not exist at all […] As far back as I can remember, said Austerlitz, I have always felt as if I had no place in reality, as if I were not there at all…” I too, saw my past as unreal, something that had happened to someone else, someone I had lost along the way and wanted to get back.

I decided to use the birth certificate to write a series of essays, because it’s the only object from my childhood I feel a strong emotional connection with, but I had false starts, this same feeling of disconnection Austerlitz/Sebald describes. I leafed through baby photographs I’d taken from my parents’, hoping they would trigger memories related to my name, my place of birth, my parents’ names, but all I saw was a blonde toddler. Krystyn blowing out birthday candles, toddling behind a man pushing a lawn mower, splashing in a baby pool. I felt nothing. I worried that, in crafting my adult life, I had worked so hard in revisions that I no longer had any memory of the original.

I decided to use the birth certificate to write a series of essays, because it’s the only object from my childhood I feel a strong emotional connection with, but I had false starts, this same feeling of disconnection Austerlitz/Sebald describes. I leafed through baby photographs I’d taken from my parents’, hoping they would trigger memories related to my name, my place of birth, my parents’ names, but all I saw was a blonde toddler. Krystyn blowing out birthday candles, toddling behind a man pushing a lawn mower, splashing in a baby pool. I felt nothing. I worried that, in crafting my adult life, I had worked so hard in revisions that I no longer had any memory of the original.

As soon as Merriam Webster came out with the Time Traveler online feature (https://www.merriam-webster.com/time-traveler), I knew it was a perfect way to think about one fragment of my birth certificate, the Date of Birth: June 27, 1987. The Time Traveler is an online tool that lists words that debuted in print in each year from 1500 to 2010. I love the dictionary, its vast, timeless knowledge. It has a mixture of orderliness and thrilling randomness. I used the Time Traveler to create various prompts for myself, until I settled on writing flash essays titled by each word that elicited a strong reaction. I ended up with eleven; there were actually sixty-two words that debuted in 1987. These eleven words title the the eleven pieces that comprise my essay “First Seen in Print in 1987, According to Merriam Webster.” The conceit of the piece allowed for it to have some whimsy and structural variation without completely losing the element of serious memory recovery. Sandy Stone has criticized the redemptive arc of some transgender memoirs, writing that “in the transsexual as text we may find the potential to map the refigured body onto conventional gender discourse and thereby disrupt it, to take advantage of the dissonances created by such a juxtaposition to fragment and reconstitute the elements of gender in new and unexpected geometries.” In this essay, I aimed to map myself onto my former self, and to use a form that organically allowed me to do that.

I had, in fact, come up with my own essayist’s version of the probe method of autobiographical memory retrieval, one of two major strategies psychologists who specialize in autobiographical memory use to cue participants’ memories (the other is diary retrieval; unlike many memoirists, I don’t keep diaries or journals). As originally designed, this method uses a series of words to trigger episodic memory; in more recent studies, images, sounds, and smells have also been used. The probe method was first conceived by Francis Galton in the 1890s. Galton, who is most widely known for essentially founding the eugenics movement, had a wide-ranging career as a Victorian “polymath,” working in statistics, sociology, meteorology, genetics, and other fields. It’s hard to ignore the irrevocable harm done by his theory of “positive eugenics,” in which encouraging the best of the human species to procreate would lead to a more positive society, but I am interested in how he believed that, by recording his associations with a series of words, he could understand more how his mind and memory worked. I came to the Time Traveler with many of the same questions he did. How does my memory work? How and what might it recall, if I force it to try?

Galton tried to control his mind, keeping it from wandering, and I tried to do the same. Soon, though, I realized that what I was writing was not discreet flash essays, but rather one large essay. Like Galton, I came around to many of the same obsessions again and again. “The actors in my mental stage were indeed very numerous, but by no means so numerous as I had imagined,” Galton wrote in the journal Brain in 1897, reporting on the findings of his self-memory probe study, which he also called a memoir. “They now seemed to be something like the actors in theatres where large processions are represented, who march off one side of the stage, and, going round by the back, come on again at the other.” So, too, did my own actors pop out on stage for a moment, only to retreat and return again. I was excited to have them there at all; the probe had worked.

I couldn’t stop thinking about sex, the awkwardness and longing of adolescence queer friendship, my association of childhood activities like rollerblading and playing Pokémon with sadness and grief, and what CDs I had in my middle school Sony Discman. Above all, though, I found my word associations tied up with memories and thoughts of my mother and my partner’s mother. I began this piece soon after my mother-in-law’s death, so it is no surprise she sprang into my writing again and again. How our mothers haunt us, even mine, who is alive and well and with whom I have a very positive adult relationship. Through memories of and with her I relive so many of the feelings of disappointment, shame, and strength that weave in and out of “First Seen in Print.” I am reminded of Virginia Woolf, whose mother, she writes, haunted her for decades after her death. “I could hear her voice, see her, imagine what she would do or say as I went about my day’s doings. She was one of the invisible presences who after all play so important a part in every life.” Woolf goes on, “Yet it is such invisible presences that the ‘subject of this memoir’ is tugged this way and that every day of his life; it is they that keep him in position.” Virginia Woolf is here examining the forces that control writers and our writing even if they are not the subject of our stories; “I see myself as a fish in a stream; deflected; held in place;” she writes, “but cannot describe the stream.”

I like short and fragmented pieces because they give me the space to attempt to describe “the stream” from different angles in the same essay. Instead of moving in a linear fashion, like some trans writers, from before to after, I find my instinct is to jump around, which is what has made working with this birth certificate and Time Traveler tool so much of a stylistic fit. No matter who I am now, I was the person on that paper when I was born, and experiences I have now remain tethered back five, ten, even thirty years. Shorter pieces allow for sentences that fold backwards and forwards on themselves, exposing the way our past experiences keep returning as we have new ones; late in the essay I write about seeing my mother-in-law for the last time: “I only waved and said goodbye like always; your mother thanked me for coming, like always. I’ve always felt that your parents feared I might take you away and never bring you back home. They will never accept that happened a decade ago.” Her presence in my life for over a decade was a thread undercutting so many experiences, and to me, it would be a disservice to try to describe the present without folding in the past.

I find that, at thirty-one, I am in a period of my life defined largely by parenting my own children. Although I am not a mother, I have had more motherhood-adjacent experiences than most non-mothers; I’ve gestated and given birth to a child, and I’ve always been my three children’s primary caregiver, and it was through these experiences that I began to gain more compassion towards the mothers in my life. It is also these experiences that made me see my emotional landscape and the “actors” from my memory tied up in motherhood. “First Seen in Print,” I think, is a very gentle treatment of my relationships with a number of mothers in my life, and that isn’t put on. The events from childhood and adolescence that I describe happened, and I’m deeply scarred by some of them. But I’ve revised myself and we’ve revised our relationship. Ultimately, the piece hinges on the life-giving relationship one can have to their mother, and the struggle to unearth the self I don’t want to write over.