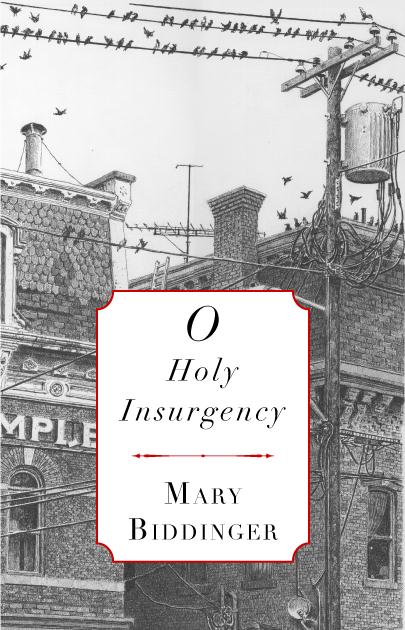

Review (from the Women Who Killed It series): O HOLY INSURGENCY by Mary Biddinger

Our Review Editor Josh English reviews his four favorite books of poetry published this year. These are the Women Who Killed It in 2013.

Review by JOSH ENGLISH

I haven’t read many books of poetry as full of stuff – suspicious characters, concrete and odd acts, weird objects, wonky practices – as Mary Biddinger’s O Holy Insurgency. Each of the regular stanzas is so jammed full of interesting objects arrayed in such curiously exact clutter, I’m startled by the end of each poem how perfectly they articulate together. Questions are never merely posed unadorned, they are themselves tangible artifacts “fringed / like the trembling grass cusp of a ravine.” But the abounding stuff-ness of the poems doesn’t slow their speaker down as clunky poeticisms or mere embroidery. In fact, there’s an exacting ear at work in these poems, and a speaker who performs her multi-object juggling act with the mouthy, punk-ass speech of a winningly artful delinquency.

O Holy Insurgency’s begins by straddling the line between Homer’s epics and Greek myth and the Elohist authors of the Old Testament. In the first poems, the speaker is awaiting the fated arrival of her beloved from an undisclosed, sacred ordinance. By the third poem, Biddinger’s speaker is cribbing King James-ish syntactical formulations: “There were wonders, but we didn’t know / they were wonders,” after spotting an “apparition” that recalls Homer’s portentous eagles as a “wet grackle / ransacking half a pound cake….” There are erotically linked Gemini (“like paper dolls / accidentally printed too close”) and a writer of odes to Jesus who worries his beloved will be stolen from him by Michael Bolton. Biddinger’s speaker acknowledges the “powers,” like the nun she admits she once flirted with becoming, and unmasks them like an episode of Scooby-Doo, with equal parts reverence and bombastic heresy. This jazzy repurposing of our oldest stories recalls the theological discomfort lapsed Catholics often exhibit, and indeed the speaker of these poems occasionally references Catholic school and church. The “holy” of the title presents itself in nearly every poem, though the cosmology is generally local and in regular flux, the rituals are secular pranks, and taboos are for suckers: “We both felt too close / to the sky, but who could stop // us?”

Just as much as the foundational texts of Western culture, sex is a central leitmotif in the universe of O Holy Insurgency; in fact, it may be intimacy that makes Biddinger’s insurgent interlopers “holy.” If many of these poems could be considered addresses to the beloved, they are also poems of self-actualization within a romantic relationship. These poems consider the beloved – his curiosities, his passions, his body, his weaknesses – as a part of the relationship’s project to describe the world as it is reconfigured by the lovers. In “The Business of It,” the speaker interrogates the hidden nature of time as gendered sexual duration:

….They’d set all

the racehorses free weeks earlier.

My body learned not to register thunder

as something beyond a disruption.

Asleep with my head on your shoulder,

it seemed fitting that the mares left

last. My own fingers demonstrated how.

You asked if it was a detonation,

or more like the euphoria of black ants

crawling one by one into a straw.

Their exodus the opposite of our bed’s

migration. And what about clocks

left gutted on a sawhorse, gold entrails.

Who could trust them again, once

the gears were subjected to daylight?

I use this overlong quotation to demonstrate three characteristics of Biddinger’s poetics. First, her poems progress by intuitive suggestion – they don’t employ unconscious “leaping,” or parataxis, and they don’t drip together like the sentences of mainstream narrative. Rather, Biddinger’s clipped lines itch at one another, they cut out the syntactical furniture of scene setting, but they do also follow a central drama. Second, in these poems, all intimacy is good intimacy, even if it is unsatisfactory (elsewhere, there is a sex scene that literally tears down the walls). Her speaker’s gentle refusal to disclose the sensation of orgasm to her lover, along with the scene’s direct eroticism, is both frank and electrifying. Finally, observe the blending of the fact of freed horses with the lack of climax (torqueing the familiar metaphor), which carries into the beloved quizzing the speaker after he watches her achieve orgasm on her own, which then transfers into the secret nature of time and the mystery of non-objective timespans.

Biddinger’s grasshopper poetics, springing from well-turned phrase and precise image to the next, are also streetfighter tough. Shuttling between the domestic and the outskirts, and often blending the two, Biddinger’s generous poems question God as fiercely and as playfully as they question romance and the world in which it matures. These poems are pleasures, and like the many pleasures they describe, these poems are challenges.