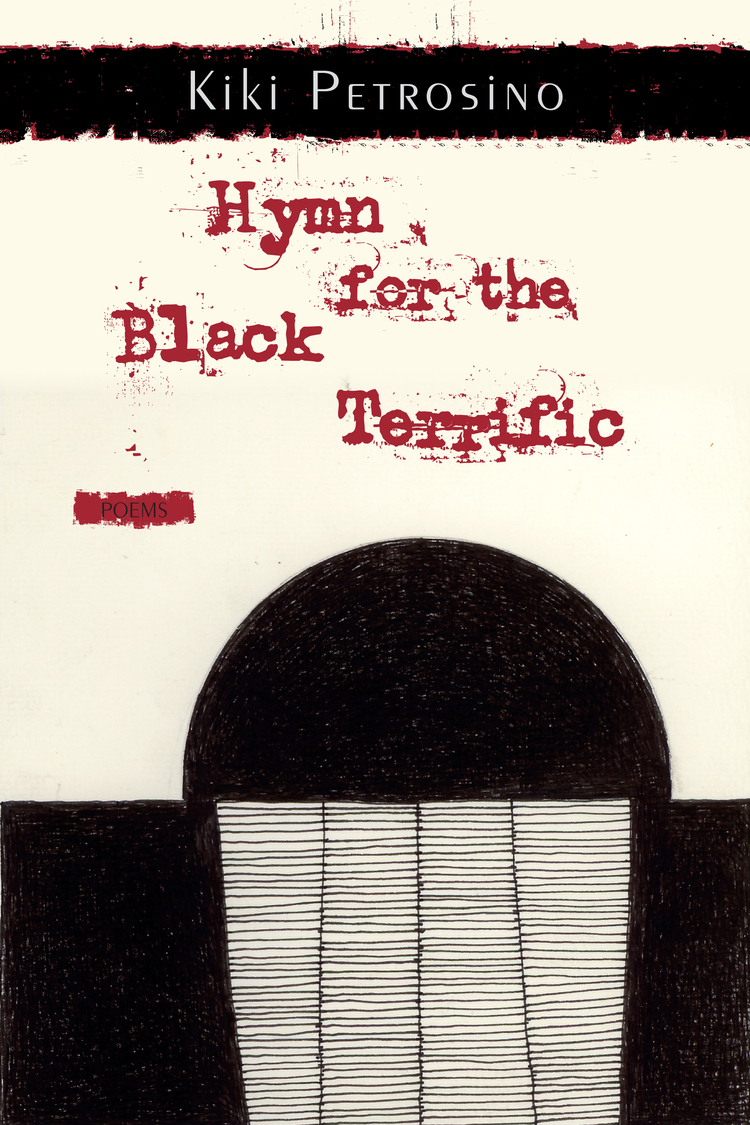

Review (from the Women Who Killed It series): HYMN FOR THE BLACK TERRIFIC by Kiki Petrosino

Our Review Editor Josh English reviews his four favorite books of poetry published this year. These are the Women Who Killed It in 2013.

Review by JOSH ENGLISH

“Oiseau Rebelle,” the first of three sections in Kiki Petrosino’s syntactically varied, duende-spattered second book, Hymn for the Black Terrific, is marked by a lexical witchiness that recalls Shakespeare’s Weird Sisters.

Readers should note the language-chess of the devious prose poem “The Terrible Test of Love.” This poem sets and resets its lexical boundaries, beginning with something like a source sentence, in which the poem’s key terms appear. Along the way, the terms are contorted and sounded for variant ringing, so that the initial sentences, “If you were scrimshaw, & this the Artic loop with miles to climb. If I had feet unslippered & a knife,” resurface metamorphosed, tousled and wily as these lines, “Pull back, my naked feet, outswarmed. My Arctic will behind a seabass door creeps back inside the clanging room of loops.” A later poem in the section sounds like an incantation of a spell, “Neither wax, nor egg, nor honey on the knife.” Many of the linguistic patterns and thinking in Hymn for the Black Terrific echo the great works of Western literature (the title is drawn from Moby Dick), but they manipulate the canon and repurpose it – they affectionately paganize it – by way of an intelligence that is so curiously stately, so wild and so extraordinarily, marvelously weird, I can’t imagine reading the book silently or just once.

In the eponymous poem, we hear the attendant of a swamp conjuring a “you.” She exercises a similar repetition and refiguring of terms as the speaker of “The Terrible Test of Love,” but she does so much more casually. This more rhythmically relaxed and conversational spell, jogging along in lots of iambs, is one of the oddest and most plainly declarative of the whole book. The summoned “you,” a male, is othered throughout the poem, dwelling among the mallow (as in marshmallow) while the speaker remains among swamp gunk, where “the starlit world goes dense with bone dust.” But the poem veers and balloons so curiously, it seems at times that the speaker and the other are having sex, with brief discussion of who gets to “get off.” Earth-mother, enchantress and sexy exile, the speaker pronounces: “A woman is a lordly thing. Hard as belts. / Mean as cat dirt in the dark. A woman rakes / herself down to the girders. A little air / seeps in, a little smoke & buzz.”

Hymn for the Black Terrific closes with two series of poems, the first of which is called “Mulattress,” which takes as its occasion a redefinition of Jeffersonian racism. The second, “Turn Back Your Head and There is the Shore,” is about a character called “the eater.” Whereas the first section was varied in form and looser in objective, the last two strictly observe form: “Mulattress” is made up of ten fifteen line, single stanza poems, the last word of each line, in italics, join together and form the appalling sentence, “They secrete less by the kidneys, and more by the glands of the skin, which gives them a very strong and disagreeable odor,” from Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia. The eater poems are all prose poems. Both sequences handle identity – and are concerned with beauty – as viewed through their respective lenses of multi-cultural racial composition and appetite and gendered beauty norms. Both series fly off the rails as the conflicting binaries (white/black, heavy/beautiful, desirous/complicated) proliferate into something broader and uncharted.

“Mulattress” begins with clear terms: “What would you trade, they / ask, if you could trade for beauty.” And while the “they” of this poem is frequently a racist majority opining from a place of monochrome privilege, Petrosino has fashioned a speaker who can repeal their demands with admirable health. She states: “A / colored body confirms a bridge, very strong / across the synapses & disagreeable / to caliper. Still, between us, this human odor.” This speaker’s own heritage is shifting and redrawn with each poem that mentions her home. She does come from a mother, “A very strong / mother like mine walks by & disagreeable / ice weeps itself to mud.” And she was born in the negative space of the repressive majority: “I live in a country they / didn’t leave for me.” Also, as you can see from the passages I’ve selected, although the poems repeat the same words in the same order, there are variations of meaning and orientation with each poem, just as each poem presents a new perimeter drawn around an aspect of racial identity, and breaks through it.

Finally, the “eater” poems are the wildest and most pleasurable of the lot. They appear to handle the eater’s desires to have a baby, assume the cultural definition of beauty, to love and be loved, to get married, all while wild and deep desires – often desires borne of the wounds past desires suffered – push her to eat and eat. But eating is also the principle pleasure of these poems. It is, again, an issue of warring binaries that also support and nurture each other. In fact, this theme of intimate yet aggressively heterogeneous pairings carries throughout the book. I first spotted it in her linked poems “Oiseau Rebelle,” which begins “A sister is the one with claws / of char across her back,” followed by the poem, “A Sister is a Thought Curving Back on Herself,” which celebrates the dreaminess of the sister – “She moves in a wish world, pressing her glass cleats down into the mulch, blistering the daisies…” – as much as the previous sister frightens. Which seems true to me of what I’ve seen of sisters, that they both hate and adore each other, equally. So, whether the eater’s longing has her shutting herself in to “plate her own tongue in white fondant,” or finding that it’s “high time for the eater to put on her wedding head & roar at the stars that cinch the sky,” the eater, and all the other women in Petrosino’s book, will continue to trade sorrow for moxie while they redefine and refine themselves and the worlds they select.