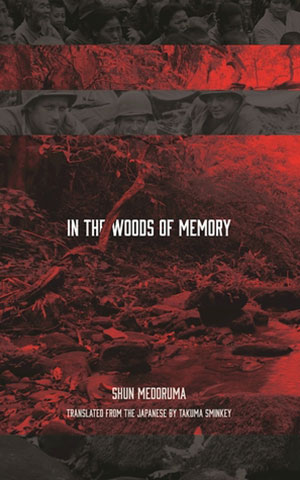

Review: IN THE WOODS OF MEMORY by Shun Medoruma

Review by Riley Bingham

The island of Okinawa, largest of the Ryukyu Arc—dividing the East China Sea from the Philippine Sea—sits four-hundred miles from Kagoshima, the southernmost tip of mainland Japan. Before 1879, when Japan officially annexed what would later become the country’s Okinawa Prefecture, the island of Okinawa existed as a largely autonomous kingdom. The island possessed its own language and culture. But Japanese occupation—in Japanese government policy, in wartime, in the passage of time itself—enforced, frayed, and generally confused Okinawa’s relationships with both its own culture and with Japan. Each passing generation strengthens this knotted distance of space, culture, politic, and memory. It is this knotted distance that hides in plain sight on every page of Okinawan Shun Medoruma’s newly translated novel In the Woods of Memory.

It is this knotted distance Medoruma reconfigures to structure his novel, which takes as its setting each end of a sixty-year interval (1945 and 2005). 1945: Sayoko, an Okinawan girl, is brutally raped by a group of occupying American soldiers. 1945: Seiji, hopelessly in love with Sayoko, stabs one of the rapists in the side with a harpoon. It is this pair of events around which Medoruma weaves a prism of narrators, through which Medoruma investigates a specific and collective, individual and communal pain. In the Woods of Memory is about Sayoko and Seiji. It is about what happened. But, more intently, the novel is about what happened to the memory of what happened. Medoruma asks after not only the lives of survivors, but also after the half-life of trauma, to measure how long it echoes.

*

Medoruma’s prose, like Okinawa, stands apart from Japan. The primary representative currents of contemporary Japanese literature that have reached the United States in the last decade are those of the Japanese fabulists and surrealists—Haruki Murakami, Yoshitomo Banana, Yoko Tawada—which arrive bearing doubled moons, dream-tinted realities, speaking dogs. Medoruma’s novel, on the other hand, presents a careful realism, but one as dexterous and strange as anything from Tawada and others. His prose is often commonplace. Artless. Through this narratorial self-effacement, Medoruma achieves a stylistic plasticity, not in the fantastic but in practical: in the psychological, temporal, and linguistic differences of his primary characters. The Okinawan girl, the American soldier, the descendants of conflict, and the Okinawan would-be avenger Seiji (to be subsequently blinded by tear gas) all have their own perspectives, their own overlapping, irreconcilable realities. Medoruma uses these palpable tensions to achieve what the best novels directly concerned with history often achieve: a slow corrective filling of the gaps in the great historical record, partnered with an awareness of the dream that is each individual’s story of history.

None of which is to describe the novel abstractly; one of Medoruma’s great achievements is his display of how one’s language affects this act of personal historiography. Seiji’s chapter—a desperate, propulsive stream of consciousness—was written entirely in Okinawan, with marginal gloss in Japanese. Moments like this remind us that Medoruma’s Japanese writings, in a way, are those of an exophonic author, an author who writes an endangered language. Takuma Sminkey, the novel’s translator, admits to the difficulty of reproducing Medoruma’s work in all its multi-lingual complexity. Not only does Okinawa have its own languages, but those languages have also been historically suppressed by the Japanese state. The politicized status of the Okinawan language, Sminkey notes, reflects itself upon Seiji. It is Seiji who exhibits the most desperate patriotism of any character in the novel, though it is also Seiji who is excluded from any Japanese acceptance by his lack of ability to speak Japanese. So language pervades, remaining present and violent. A living, if fading, memory.

Memory, unsurprisingly, is the crux of Medoruma’s project. In the Woods of Memory asks: what is remembered, what is repressed, and why? Answers don’t come easy. The generational decay of memory’s valuation is both laid upon and lifted from the shoulders of the young, the newly occupied. The loss of memory is laid upon and lifted from the elder generation, their stringent repression of their own experience. Who is responsible for a community’s memory? How is it that events which have happened in living memory find themselves completely lacking of the codified bona fides of history? This is Medoruma’s target, the specter of a great forgetting.

*

There are estimates that, during the Battle of Okinawa and the subsequent American occupation of the island, over ten-thousand Okinawan women were raped. Official reports of rape number below one-hundred. This period of atrocity in Okinawa was one marked by a silence. A silence that, in the novel, seeps into an entire community’s memory. A silence that fixes itself in the flux of the Okinawan landscape.

Sixty years after the rape of Sayako, a village girl, her once-friend Hisako—now living in mainland Japan—begins to have dreams. She is called back to the island. She meets Fumi, the first chapter’s narrator, who draws out the memories Hisako has repressed, as they tour the island. Fumi and her son take Hisako to the titular woods, to the cave where Seiji made his final stand against the American soldiers, where he was shot and blinded with tear gas. These are the woods of memory, the same woods once destroyed by American assault. Next, they visit the beach where they both witnessed Sayako’s abduction:

—Is this it?

Fumi smiled wryly at Hisako’s question.

—Whenever I come here, I really feel disgusted at Okinawans. Even though it was small, this was a beautiful beach. As payback for accepting the US bases, they’ve been destroying the environment with public construction projects, and calling it stimulus for the local community. This beach was destroyed ten years ago.…Besides the beach, we’ve also lost the screwpine thicket. The whole area’s changed beyond all recognition…But standing here like this, I can still picture what happened sixty years ago: how the Americans swam across from that port over there, came running up the beach here, and then carried Sayoko off to, uh,….I guess the screwpine thicket was over there, but it’s changed so much that I’m not sure….You can remember, can’t you?

Following Fumi’s gaze, Hisako looked over and tried to picture a thicket of screwpine trees in the area covered with the terraced embankment. She then tried to picture several American soldiers carrying off a girl. But the concrete scenery seemed to plaster over what had happened here, leaving Hisako to fumble through her dim memories.

What does it mean to metaphorize memory as a forest when the trees have been bombed to splinter and ash? How is trauma recalled when occupation has changed the site of memory? Medoruma—as much an activist in his life as he is a novelist—is playing a vital part in drawing attention to a largely-unspoken chapter of the second world war.

*

The question arises, upon finishing In the Woods of Memory, of whether or not Medoruma himself contributes to that silence; of the novel’s nine narrators, none are Sayoko herself. When so many characters are given space to react to Sayoko’s rape, from her friends to her would-be-avenger, and even one of the American rapists, it feels inexplicable that Sayoko herself is never offered her own accounting. Instead, it often feels as if Sayoko were not even alive; the many narrators of the novel serve to wheel over the tragedy of Sayoko like birds, skirt around her edges like chalk. Late in the novel we see artwork of Sayoko’s, the expressions of a silent interior. Besides this brief glimpse, Sayoko’s presence and memory is that of a ghost: she haunts the periphery of the town’s consciousness, disappearing with near completion after her rape triggers the events of the novel.

It is worth noting that Kyle Ikeda’s afterward for this edition of the novel acknowledges this omission, and offers explanations from both Medoruma himself and scholar Alisa Holm. Medoruma, according to Ikeda, “responded that Sayoko is unable to narrate her trauma, and that there are undoubtedly numerous war survivors who have never been able to talk about their traumatic war experiences.” Holm, on the other hand, offers “that Sayoko’s ‘voice’ is her paintings, and that her rendering of her trauma through visual media is her way of expressing her experience. Articulation through narrative is not the only mode of processing and expressing the traumatic.” Both Ikeda and Holm make fair points. Stone Bridge Press does well in providing this back-matter for the novel; in beginning a conversation. The choices Medoruma makes in this territory deserve attention. If the novel can speak for itself, it does so in its own execution, one which struggles against the reduction of the work to any simple litigation. In the Woods of Memory’s structure resists isolation not only of any character, but of any of its subjects. This is a novel about war, about history, about rape, yes. But more importantly it is about the synthesis of all of these subjects, the moments of intersection: of individual and collective traumas, memory and community, language and history.

*

It seems odd, in hindsight, to know that In the Woods of Memory was written and published serially, each chapter appearing months apart from its predecessors and successors; the novel relies so greatly upon the force of its accumulated power, of the lives of its characters drawn into a single gesture, one arrangement. But an arrangement of what kind? Is it one long arc? Or the shattered, smeared, and scattered suggestion of an arc? Or is it something altogether more diffuse, each story existing in a gaseous state among the others, motes of dust trapped in a jar?

But there’s the central tension of the book: the history that one person experiences is only the history of the event until another person tells their own story. And so the recursive succession of records goes, until the process coaxes out what is difficult, what is buried, what has waited, unsaid, in the margins of every story that came before it. Has Sayoko’s story been told, now, through so many indirections? In the Woods of Memory enacts this process, these questions. It gives space for a story. And a story again, and again, until something, finally, coheres, seems to hold all these stories together.