Review: TO THINK OF HER WRITING AWASH IN LIGHT by Linda Russo

To Think of Her Writing Awash In Light: Lyrical Essays on Dorothy Wordsworth, Emily Dickinson, Hettie Jones, Joanne Kyger and Anne Waldman

Linda Russo

Subito Press

65 pages

Review by RBrown

Linda Russo begins her collection of creative and critical essays with a quote from Gertrude Stein: “Analysis is a womanly word./ It means they discover there are laws.” In To Think of Her Writing Awash In Light, Russo examines the laws of looking. She questions who has the right to look and what lens we should be looking through. Russo works to cast a new light on four influential female writers, Dorothy Wordsworth, Emily Dickinson, Hettie Jones, and Anne Waldman, calling for a new way of looking at each author.

These essays are lyrical in the fullest sense of the word. Each essay is highly associative in nature, pulling strands from Russo’s life and experiences while studying these writers and her personal reflection alongside the words of the writers themselves. Three of the essays begin in the same place, an examination of the physical space which the writer inhabited, and then drift through the emotional landscape surrounding the work or the writers themselves. In the midst of this, Russo is a careful guide. She takes the reader down a winding path, where each move feels planned, not unexpected, yet still not forced. There is a sense of discovery in each new turn, a feeling of walking alongside Russo through the physical and emotional terrain, learning as she learns, seeing as she sees.

Russo seems to be conscious of her role, both as the one who looks and the one who holds the looking glass. She writes critically of the predominantly male gaze that controlled the narratives of Dorothy Wordsworth and Hettie Jones and reduced them to the wives of capital P poets. This male gaze is addressed directly in “(Dorothy Wordsworth): Weeding/Sowing/Stucking/Walking,” by including direct quotations of William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Thomas De Quincy describing Dorothy, reducing her to a description of her body, her eyes (9).

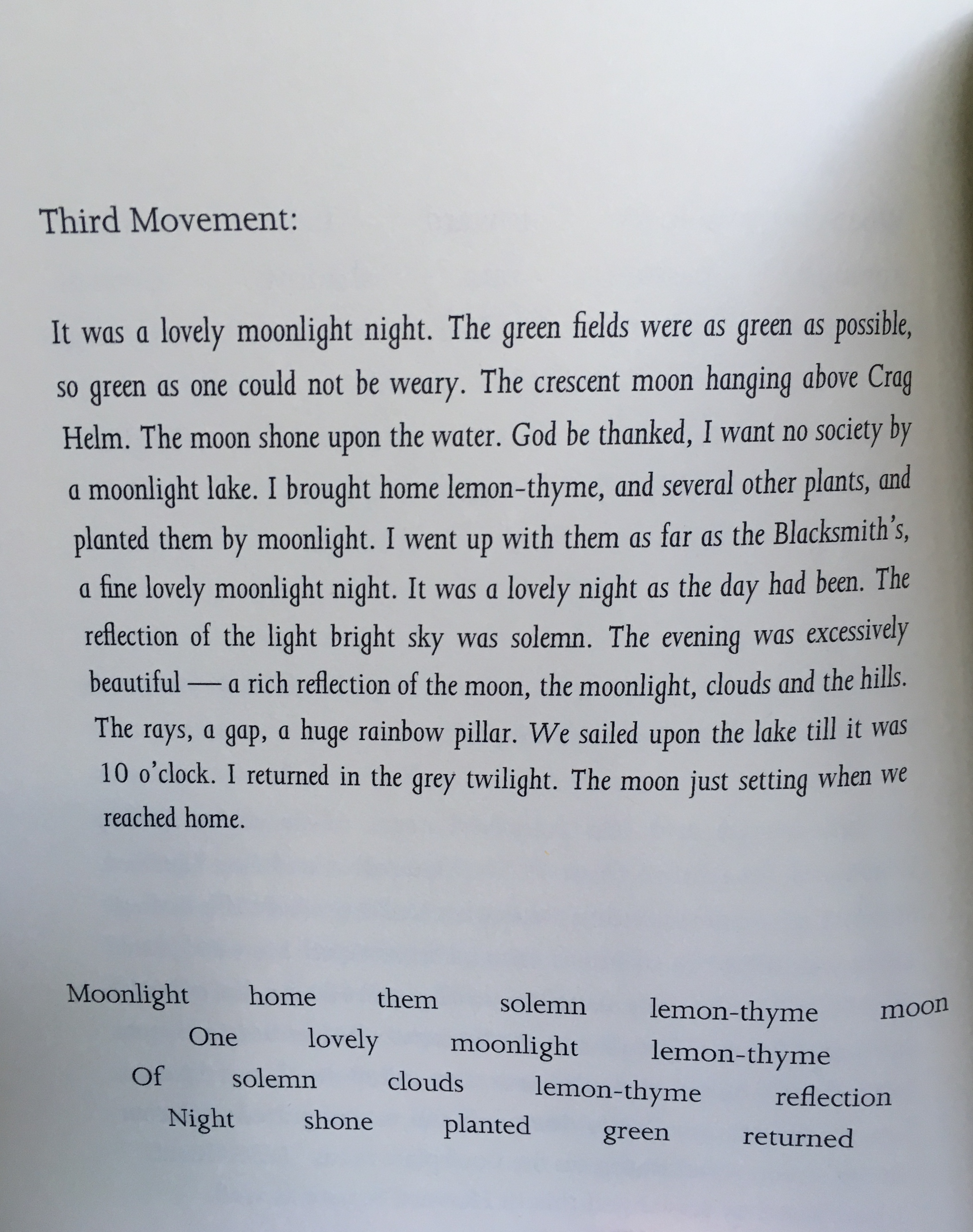

Russo walks a fine line in her own looking. In discussing the way that William Wordsworth used Dorothy’s journals for inspiration, Russo, herself, erases and rearranges Dorothy’s words, to highlight their poetic nature:

Each movement begins with Dorothy’s own words, which Russo uses to create a pseudo erasure. These erasures begin in a straightforward manner, but as they continue, they become more associative in nature, evolving from traditional erasure to a kind of re-worked lexicon created from Dorothy’s journals. Through the erasures, we see not only the lens of the William over his wife’s writing, but also the lens of Russo herself. In this way, Russo uses the lyrical essay to show her own thought pattern, her own way of viewing the word. She acknowledges this most directly in her analysis of Emily Dickinson. After spending nearly two pages describing Dickinson’s desk and writing area, Russo writes, “I’m not sure I’ve ever seen the desk, or if I ever will” (23). She seems to be asking what it means to really see, to understand what is seen. Russo creates an image of the writers she is examining, but still recognizes that she has constructed this image: “My Emily Dickinson,” she writes, italics her own (31)–referring to her imagining of Emily Dickinson and connecting to My Emily Dickinson, by Susan Howe, a similar kind of lyric exploration of Dickinson’s work.

I question, however, if this movement is enough. Before entering the Emily Dickinson House, Russo writes, “There is the matter of how we are permitted to look at things” (16), referring to the control of the academy over Dickinson’s work and image. This control, enacted after Dickinson’s death, mirrors that control that Dorothy Wordsworth and Hettie Jones were subjected to during their lives. “Is she a poet?” Russo asks of Hettie Jones (44). The answer is yes. The answer, at the time, Russo says, was no. The issue here remains: who is it that does the looking? Who is it that decides if and when a woman is a poet? As Russo sheds light on these questions, we are still aware of her role as our guide through the text. She shows the way these writers have been seen in the past, the incomplete examining, the unfollowed path and yet, her gaze is still present. It is still Russo’s Dickinson, Russo’s light that we are following.

Perhaps the final essay, “(Joanne Kyger and Anne Waldman): Reading Iovis in Bolinas” moves us toward a more clear answer. While still lyrical and associative, this final part departs from the pattern of the first three. Instead of following Russo as she moves through the physical and emotional headspace of the poet, we witness Iovis as it is read aloud among friends. This essay is the most formal of the group, directly addressing the work itself. The function of the essay as literary criticism is more clearly seen, brought forward in a way that reminds us of genre conventions, while still maintaining the lyric, convention defying form of the rest of the collect by framing the essay around a conversation between friends who are Iovis together. Invoking the critic’s voice, Russo writes: “Iovis challenges the generic boundaries of the masculine epic tradition.” (48). This movement toward the formal allows Russo to introduce the central thesis of the collection, the integral idea.

It begins with the occasion of the essay–the insistence of Joanne Kyger “that no one can read Iovis alone, that it’s meant to be read aloud” and the following group reading of Iovis (45). This act of reading aloud is an act of reading aloud as a group. The key here is both the reader and the listener, the group reading and listening together. There is no space for a singular interpretation in the communal reading. It is in this group understanding that Waldman’s work is able to stand. Iovis becomes the guide, carrying us through the essay. In the end, Russo concludes, “It must be read communally… It’s simply too much to take in alone” (53). It is the group of voices that bring the piece to life, the variety of experiences and perspectives. “It is how we make a space,” Russo writes (54), and here we see the whole collection open up, one voice into many, creating the space, starting the conversation.