Review: THE YEAR OF PERFECT HAPPINESS by Becky Adnot-Haynes

The Year of Perfect Happiness

Becky Adnot-Haynes

2014

University of North Texas Press

192 pages

Review by CHASE BURKE

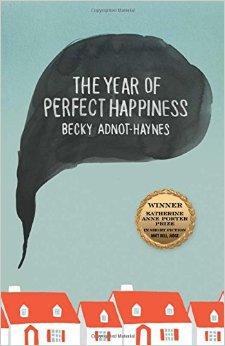

Take a quick look at the cover of Becky Adnot-Haynes’s collection of stories The Year of Perfect Happiness, which won the 2014 Katherine Anne Porter Prize in short fiction. Above a row of tidy red-and-white houses floats a huge cloud of chimney smoke like a speech bubble. The book’s title is scrawled neatly into the cloud, completing an airborne toxic event of “perfect happiness.” It’s a great, sardonic cover that manifests the triplet dark clouds of indecision, anxiety, and malaise pursuing the collection’s characters, all set against a pretty blue sky. While there’s a lot to discuss in this book—including celebrity, sports, disease, loneliness—the most evident thematic concern is how people choose to balance their desires for happiness with those of the people they love.

In an interview with Hobart, Adnot-Haynes explains her fascination with the human capacity for “bad behavior,” specifically how a person might “[sabotage] herself and her relationships without fully knowing why, at least not when the story begins.” In The Year of Perfect Happiness, Adnot-Haynes confronts a certain kind of suburban ennui by showcasing otherwise decent people during their most selfish or unkind moments. Despite the drama inherent in these stories—couples separate, animals die, cruelties are exchanged—the writing is direct, lean, even playful, as evidenced by the opening to “The Second Wife”:

The first wife was dead, which called for a reverence of spirit when speaking of her, a lowered voice and furrowed, sympathetic brow, but the problem was that the second wife didn’t feel reverent. She felt fascinated, curious—but not reverent. She liked to ask questions about her, questions like which sections of the newspaper had she enjoyed most and did she always cook a vegetable side dish with dinner (the second wife did not) and what were her thoughts on movies in which a man and a woman switched bodies?

Through its structure and tone, this story’s beginning injects a serious subject with humor without being overtly unkind. Consider the second wife’s string of unimportant questions, the husband’s later “gingerliness” in approaching them, the fact that no one is given a name. These three feel like characters instead of people, which helps to distance the subject of death from the central plot of a woman wanting to know more about who her husband was in the past. The story necessarily complicates, but that tension is maintained, as it is in most of these stories.

In “Baby Baby,” an aimless young woman frustrated with her life lies about being pregnant to her realtor and boyfriend. The premise is something of a joke gone too far—Mina wears a foam pregnancy belly around the realtor for reasons she can’t quite articulate, and acts completely normal around her partner—she likes the twin feelings of being showered with attention and of harboring a secret. Adnot-Haynes widens the scope of Mina’s deception until some kind of fallout is inevitable, leaving Mina to wonder about the very nature of her relationship:

How long can you be with someone who sees you at your very worst, who knows the things about you that should be your treasured secrets, that should be held deep inside of you, apart from the world? It’s like having your house burglarized, strangers touching your toothpaste and soap. It’s like having your insides turned out for everyone to look at.

Pregnancy appears elsewhere in the collection. In “Rough Like Wool,” a woman named Nell joins an Internet forum for expectant mothers, where she feels “unworthy” because her pregnancy is easy—she has no real problems, no sickness, no trouble. So she tells the women that she has Morgellons, a rarely studied phenomenon characterized by phantom strands reported to grow out of the body. Her husband has dedicated his career to understanding the condition, and Nell uses their conversations about it to fuel her forum posts and to get the kind of sympathy from these online strangers that she feels she doesn’t get from her husband, who is both far older and more successful than she is. What’s clear from Adnot-Haynes’s prose is that Nell’s husband is a decent person, as is Nell. What’s also clear is that even decent people can be bad at relating to one another.

So how do you explain your feelings of unhappiness when you think you should be happy? Sometimes you don’t explain anything, you simply “take action,” as Abbot chooses to do in “The Natural Progression of Things.” (This title is its own small joke, a comparison of human longing with the Floridian food chain.) Of course, Abbot’s action-taking isn’t much—he’s just trying to impress someone he knows is out of his league. But the sentiment holds: action-takers “get out of stale marriages, end friendships that have soured. They kiss the people they want to kiss.” And the non-action-takers? In Abbot’s eyes, “sometimes wonderful, lucky things come and the non-action-takers turn them to shit with their poisonous, lazy touch.” He’s terrified of life passing him by.

In both the title story and “The Men,” the action-taking protagonists are unable to attain their goals, though only one is willing to reflect on the reason why. Davis, on a yearlong quest for “perfect happiness,” plans to travel the country and leave a place only “when [his] happiness begins to sour.” As it turns out, it sours quickly. That he leaves a wake of hurt feelings behind him is beside the point, because those feelings aren’t his. In “The Men,” Addy loves breaking up with her boyfriends because of the feeling of control it gives her. To her, a breakup is “like a work of art,” or something to savor. When she finds herself unable to end her current relationship, she can’t understand why, until she comes to a kind of realization that for so long “she has traded something real and good for the pleasure of a resulting story, an amusing little narrative.” Unlike Davis, she wonders if that story she has told herself so many times is one that makes her happy.

The Year of Perfect Happiness is about more than just relationships between men and women—”Velvet Canyon” might be the best story about drugs and a mother-daughter hike in the desert that this reviewer has read—though they make up a majority of the book. This isn’t a bad thing at all, because Adnot-Haynes writes so confidently about the ways we try to balance what we want for ourselves with what we think we owe the people we’re committed to. Ultimately, this is a book concerned with the emotional states of a particular demographic of young men and women, but it’s rarely kind to them, much in the way that they are rarely kind to each other. Adnot-Haynes is thus as critical of her characters as she is sympathetic toward them. So when an act of kindness appears, you latch onto it, because it is kindness that leads to happiness. Back to “Velvet Canyon” for a second—that mother and daughter having a good night together, well, that’s one day’s worth of happiness. Count them one by one.