Review: AN EXTRAORDINARY THEORY OF OBJECTS by Stephanie LaCava

Review by ETHEL ROHAN

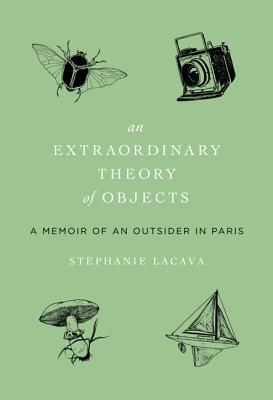

What is most exceptional about Stephanie LaCava’s memoir The Extraordinary Theory of Objects is that it contains little of Stephanie LaCava. Through story, footnotes, and illustrations by Matthew Nelson, the book chronicles a wide range of people and, most brilliantly, objects. In the first sentence of her introduction, LaCava declares, “I was always strange.” What follows in this brief but gripping memoir is the chronicling of her desire, separateness, depression, loneliness, and her inability to feel settled in the world and within herself. Since childhood, LaCava sought out stories and objects both ordinary and extraordinary. Her imagination and sense of awe distanced her from reality and freed her from everyday drudgery: “Some people’s bodies need to make extra blood cells or insulin for survival; mine manufactured fantasy.” This relentless curiosity and attachment to things is a capacity she both cherishes and at times laments, recognizing that in childhood she coveted unusual things to distract herself from her unraveling.

The Extraordinary Theory of Objects is LaCava’s exploration of what went wrong in her life to lead to her feelings of alienation and her obsessive compulsions: Was it chemical? Social awkwardness? Was it, as a friend suggested in adulthood, her skewed point of view? The frequent absence of a father she adored? Or was it her traumatic move from New York to a remote suburb of Paris when she was twelve years old and from which she never seemed to fully recover? When her mother gifts her with lilies of the valley from their garden in Le Vésinet, LaCava writes, “She had planted them when we arrived. So much time had gone by since then, nearly two years, and now they were here and I wasn’t any longer.” LaCava collected objects before her move to France, but in the wake of the relocation her impulsiveness and sense of isolation escalated. She surrounded herself with objects to make her new home feel more permanent, collecting such items as a mushroom; opal, violets, cardigans; negligees; whale’s tooth; skeleton key; an ancient Egyptian sarcophagus; poison arrow tree frog figurines. In her fascinating footnotes, LaCava records the histories of the objects she collects or comes in contact with. Here’s one such footnote:

Scotsman David Brewster grew up in Inchbonny, where he spent time with a young blacksmith, James Vetch, who taught him about telescope mirrors. Fascinated by optics, Brewster, an inventor and philosopher, continued to explore the field only to discover in 1816 he could create beautiful patterns with lace, beads, and glass pieces reflected in many folds. The invention of the kaleidoscope caused a sensation that, sadly for Brewster, led to immediate copies and mass production of the marvelous little toy, owing to an improperly worded patent. What is most alluring about the kaleidoscope, and perhaps what contributed to its great popularity in the nineteenth century, is the human draw to symmetry—in beautiful faces, flowers, and other phenomenon.

In researching the history of objects and people, LaCava is also trying to figure out herself. As she aligned herself more and more with objects—manifested by her collections and her growing attachment to the inanimate—she became almost as numb and as fragile as the objects themselves. Ultimately, she collected strange and often ugly-beautiful dead objects without volition because those were the things she most identified with and which, ironically, also made her feel less alone and more alive. Her collections represented her inner chaos and her need to order that which she could.

When I fell apart at thirteen in France, I didn’t lose my unfounded trust in others and the naïveté that ruled my youth, but I did misplace innate excitement, hope, and a will to live. A loss of control in my surroundings contributed to an active, throbbing depression. Spending those first full days in Le Vésinet alone—cut off—led to interactions with only objects and stories, which came to form the map of my breakdown and survival. What saved me, in the end, was my fear of change transforming into raw wonder and wanderlust.

In her epilogue, LaCava concludes, “My strangeness proved to be chemical, which meant objects would exist in and out of France, in and out of childhood.” In adulthood, however, the collections don’t hold the same meanings:

“[The mushroom] had stayed in my collection until we moved back to the States. Its shriveled little body was then lost somewhere along the way. My other objects and collections still existed, though they’d started to morph to represent real, critical, connected themes rather than random things. People were no longer classified like the deities of Greek mythology, or the tidy trays of insects at Deyrolle. I’d kept all the objects because they were evidence of the beauty in the unusual, not as empty souvenirs of France.”

In the memoir’s final poignant scene, we see a horse built of paper and blue masking tape and we intuit LaCava’s desire for the people and the love connected to objects. Again from the footnotes:

“At the close of [“Dali’s Mustache”], Halsman says, ‘The great lesson of Dali’s mustache is that we must all patiently or impatiently grow within us something that makes us different, unique, and irreplaceable.’”

The Extraordinary Theory of Objects is enduring testimony to LaCava’s Dali’s mustache.