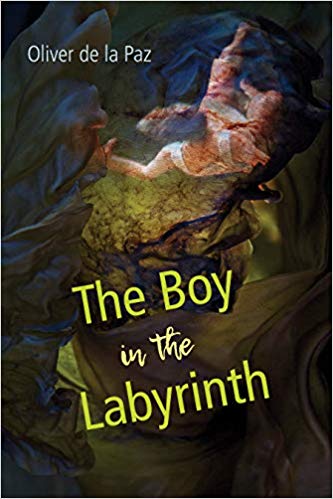

Review: THE BOY IN THE LABYRINTH by Oliver de la Paz

Review by Tyra Isaacs

Oliver de la Paz’s The Boy in the Labyrinth is a retelling of the Greek myth of Theseus and the Minotaur. But as the father of two autistic children, de la Paz takes the classic tale of a hero’s lone battalion against the monster, and infuses it with tenderness, mystery. de la Paz’s use of language channels the emotional intensity of neurodivergence not by apostatizing it via tragedy and suspense, but by contemplating neurodivergence as a relationship of intimacy and an enigmatic unknowability. Theseus and the Minotaur is thus retold from the perspective of “the boy.” The boy transverses a labyrinth and ultimately meets the minotaur as the journey is cataloged by a series of autism screening questionnaires, vivid imagery and diction, and a story that is woven together with beautiful and tender language.

“Does your child have difficulty have difficulty understanding basic things (“just can’t get it”)?”

These are the types of screening questions that de la Paz’s poetry refuses to answer with a “yes,” ”no,” or “maybe.”

“Against the backdrop of the tree he looks so small.”

Instead, the prose manipulates the unyielding form of the screening questionnaire by counteracting it with an answer whose complexity and richness are just as unyielding as the question it seeks to answer. However, these rich answers are a plea for connection and a desire for vocalizing that which often goes unheard. The novel’s combination of questionnaires adds depth to a form incapable of rendering such. Therefore, the novel’s poetry demands a new reading of Autism and new readings that employ emotional complexity. “The boy” as a character demands reading as worthy of epic potential, and the prose makes sure to acknowledge the boy’s engagement with this same potential in the Labyrinth and his relationship with the Minotaur.

de la Paz beautifully renders neurodivergence as a relationship of complex ambiguity. The prose wonderfully yields to neurodivergence as an identity worthy of epic means and an experience transmuted by its need for intimacy and understanding.

I have asked de la Paz a few questions about his work!

1.) The book begins with an apology. I’d like to dig deeper into that. What are you apologizing for? And does that apology speak to your experience as a writer? A father? Both?

The book was written over a span of ten years and as the years had passed, my understanding of my position as an advocate informed the knowledge that by committing to the page my insight into parenting neurodiverse kids I might be creating a caricature of them affixed permanently to the page. It’s a gesture of failure and worry that I am doing harm. And I suppose, it’s a natural worry for writers who are writing about loved ones—that the work you create does harm.

2.) “The Boy” in the Labyrinth is not named, however, I have noticed a series of other identifiers. The parable of the myth refers to him as “the boy,” the questionnaires as “your child.” Is there anything to the relationship between “the boy’s” namelessness and the exterior names placed upon him?

I didn’t want readers to immediately think that “the boy” was Theseus because that would immediately suggest one type of reading of the work leading to the Minotaur’s death. I wanted there to be mystery. I also generally enjoy working with allegory. It’s a type of story-telling that is instructive but also cunningly deceitful. You think the story is telling you one thing, but it’s actually telling another. The two stories are braided together and yet are separate. The child of the questionnaire and the boy in the labyrinth are and are not the same boy. Just as the child, as defined by the questionnaire, cannot be defined by the questionnaire. I wanted to suggest an archetype in the same way that I also want to refute an archetype.

3.) Let’s talk about form! More, specifically, form and meaning. The first thing I’d like to ask in this regard is the screening portions of your book. They have an interesting form. If you don’t mind, let’s break them down. Sometimes the answers to the screening questions are more complex than the question! Are the answers for the screening meant to be “answers?” Or are they attempts to do something else?

These are modeled after the actual Autism Screening Questionnaire diagnostic tools my wife and I were given to assess our sons. There really are only two possible answers the questionnaires can account for—“yes” and “no.” And yet that’s the failure of the tool, because the language of the diagnostic tool is for narrowing a perspective rather than widening it. The responses to the questionnaire as readers see them in the poem are a neurotypical parent’s quarrel with the endeavor of responding.

4.) Next is Theseus and the Minotaur. I’ve always thought of the myth as one of heroism, battle, and tragedy. It’s full of those tropes. Am I correct? How closely does the boy relate to such tropes? What is the boy’s relationship to these tropes?

Indeed, that’s why myths are so useful—those tropes are wonderful shorthand. And yes, you might also notice that the book is structured as a tragedy, but I think it breaks that trope. There’s an expectation of conquest by alluding to Theseus and the Minotaur, but the boy doesn’t conquer the minotaur. There’s the expectation of a brutal slaying (either the boy or the minotaur) but what instead happens is intimacy. There’s a lot of stuff about fathers and sons, starting with the poem about Minos and perhaps slight echoes of Daedalus and Icarus. All of these are tropes that I want to activate and also trouble. So the nameless boy who traverses the labyrinth has his own narrative which, despite the history of the myth, he does on his own accord. Even the string given to Theseus by Ariadne runs out. This boy’s on his own.

5.) Let’s talk about the beast. Throughout the piece, the minotaur is omnipresent. Could you say something about the minotaur?

Monstrosity is often used to other and that was immediately a concern for me as I gained distance from this work. I didn’t want readers to imagine that the beast was in any way an articulation of neurodivergence. Rather, I wanted the beast to serve as the unknown—things that are less concrete and more spiritual. I don’t know if I succeed in this regard and that’s partially what compelled me to right the secondary and tertiary sequences of the book—the questionnaires and test problems. The beast is the threshold guardian of the epic—that which is the impediment in the journey of the hero. And yet, instead of being slain it is understood, or at least, the endeavor to understand revises the hero’s journey.