Review: Poetry Book Trio for National Poetry Month!

Terrible Blooms by Melissa Stein

Reviewed by Elise LakeyTerrible Blooms, the second collection from Melissa Stein, serves as an elegy for the body’s redemption as it mourns what innocence must lose in order to be transformed again. Her newest collection diverges from Rough Honey, her debut book published in 2010, as it metamorphizes from a focus on persona into a focus on shorter, seemingly autobiographical poems with less narrative and more exploration of lyric obsessions—such as swans that fold into themselves, scars that cut into the earth, and flowers that bloom as blades. These obsessions swirl around the book and invite the reader to investigate and lean into their own layers of trauma and lust—just as the speaker states: “Let’s watch what’s tender / choke or breathe. Try / to make a mark on me” (5). Terrible Blooms is a dynamic collection of opposing forces and the celebration of the cyclical nature between lightness and darkness, drowning and floating, and our role in creating each of these spaces as Stein recreates the body into something transcendent rather than broken.

Divided into four sections, the collection opens up with the poem, “Harder,” declaring “If you’re going to storm, / I said, do it harder” (5). These opening lines invite in a tidal wave that never slows in intensity throughout the collection, building up to poems like “Lemon and cedar” and the “Quarry” series. While the quarry series is layered throughout, “Lemon and cedar” is the climax of section one, asking “What is so pure as grief?” (19). This opening rhetorical question haunts the rest of the collection as twisted dreams take hold of the speakers—who feel polluted and clouded in judgment. The mantra of the collection is “to lose what’s lost—it’s all born lost.” The speakers in the poem are found and discarded again by lovers, families, and the earth—though these same nihilist meditations can transform into lust and the longing for children. The hospital introduces the theme of contained suffering either in the domestic world or throughout outdoor spaces, such as quarries or fields.

The quarry poems (all titled “Quarry”) serve as anchors throughout each section and carry on layered meaning as the collection progresses. Unlike the fragmented narrative of the collection, the quarry poems move in a more linear way: from deepening darkness to flighting hope. They track the growth of two children from naïveté into a loss of innocence. While the four sections themselves aren’t neatly divided up that way (from dark to light), the same narrative is present throughout and carries the collection to its ultimate resolution.

Overall, the “Quarry” series emphasizes Stein’s longing for and obsessions with scars and violence: the same scars on the earth are the scars on our body and the violence done to the earth is within our homes (such as with the blasted rock of the quarry and the unwanted man who comes to visit). In an interview with the Kenyon Review, Stein states, “Even in the midst of willed damage and destruction, violence to the earth, [there is] the possibility of floating, lightness, freedom—although in [“Quarry”], the darkness circles back around.” This darkness envelopes but eludes the reader as they transverse the quiet and disturbing landscape of Stein’s unsettling world, reaching for fallen petals that turn to ice: beauty mixed with terror. Terrible Blooms, calls for us to see the violence and pain in the world and dares us to find beauty in the bruises it leaves, for “What is so pure as grief?”

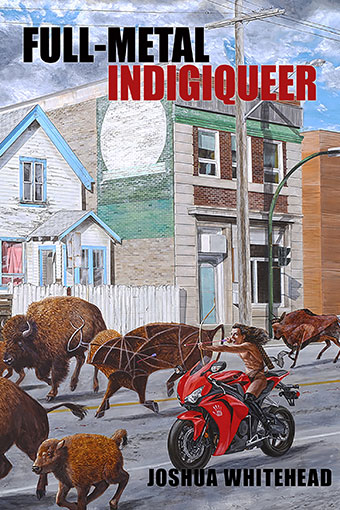

FULL-METAL INDIGIQUEER by Joshua Whitehead

Reviewed by Reilly CoxInfection is inherently involved in any process of colonization. At its smallest scale, it is the infection of a singular body as a virus colonizes its new host and ravages that microcosm. At its next level, this process is iterated as entire populations fall ill to colonizers, whether through intentional harm or by incidental violence. At its final level, the land becomes the ravaged host as the new population moves furiously across the macrocosm, at once laying claim to it while also allowing the land to grow ill and desolate, having never truly been a part of it and knowing that the process can just start again.

Joshua Whitehead’s collection Full-Metal Indigiqueer engages with each of these levels of infection and colonization while pushing even further into realms not at first considered, making a paracosm in which language, literature, and culture are reclaimed through deterioration from their more familiar, violent states. It is that language that first strikes a reader as they enter into their world. Is this a computing code for an organic processor? Is this a DNA sequence for one of the many persons whose identities have been rejected, not only by their colonizers but in turn by their own cultures as toxic standards seep into the waters? Or is it just the closest approximation of a language that this Two-Spirit, Oji-Cree poet must now create for lack of one that might truly speak?

This collection follows a trickster spirit Zoa as they move through this world that has become unfamiliar to them. In “THEORIES OF NDN CHAOS,” one of the more English-centered poems, Zoa considers how chaos (sickness, joy, queerness) is a part of their very being at this point: “if i were a scientific man / imagine / two drops / in a test tube / blood & oil / murkiness / diverging.” Or there is “E/ESPYWITHMYLITTLE(I)” that begins “: :: :installingchildhoodsoftware : : wherethehelliswaldoapplicationinstalled: : :” which almost seems to set the reader up for a joke before starting the poem proper with “there is a guilt / that pulls.” So much of this account, Zoa shapes with found images of historical figures or diagrams of language or genitalia or forms that break across the page that any language that attempts to neatly describe it fails. It is a hybrid text to the extreme, with every page reinventing the rules of the text. In both of these poems, as in the rest of the collection, infection and colonization seep into language, into imagery, into narrative, sometimes in an attempt to reverse the process—to infect the infector, to colonize the colonizer—but sometimes Zoa’s infection forms a sort of story, a mourning song.

One of the most heartrending entries is Whitehead’s “MIHKOKWANIY,” which translates to “rose,” a piece in memory of Whitehead’s murdered grandmother. In the piece, the speaker switches between Cree and English regularly, sometimes translating, sometimes keeping a word untouched as a gift to this ancestor, a beauty queen who was kind and loving and who was killed by a white man, Steven Kozurak. Kozurak assaulted and strangled Mihkokwaniy and was found innocent by a jury who pitied him for being messed up on a mixture of drugs when he murdered this woman. In the margins of five of the six pages of this poem, Whitehead repeats Kozurak’s mugshot, distorted over and over again, at once refusing to let Kozurak’s crime disappear while simultaneously allowing him to be forgotten as the reader returns to the beautiful descriptions of the grandmother’s grave where rabbits visit, or the story of the family trying to recover from this loss. In this case, Kozurak is the infection that need be excised from the story of Whitehead’s grandmother. While his name and visage exist in the text, Whitehead keeps their grandmother’s name and face safe from him. It is only in the final moments of the text, after Kozurak has been expunged, that we finally get her name: “this is my kokum / & and her name is Rose Whitehead; & she is a / beauty queen extraordinaire,” followed by a picture of Rose smiling over her shoulder, cooking a meal for her family.

Full-Metal Indigiqueer is a collection that transforms on every page. It is heart-breaking, gut-punching, brain-breaking, and not to be missed. Follow Zoa. Be rent.

Darwin's Mother by Sarah Rose Nordgern

Reviewed by Elizabeth TheriotWe are animals named human and we name and categorize, we prod at the world, we ask of it relentlessly. In Darwin’s Mother, Sarah Rose Nordgern prods at the proding, asks at the asking. As the book wryly borrows the voices of scientists and other curators of knowledge, the insistent collecting of evidence and explanation becomes its own colonialism, a seeing without seeing. Women, as the collection’s title suggests, hold the center; from the first woman, “a complex creature” who is “headless, all body” to the book’s titular matron, who shifts between the corporeality of “good clean blood” and transparency, “a strip of gauze/hung over a side chair.” In these pages women are the most observed animals, bulging with stolen space and parts arranged by scientifically-minded men. Darwin’s Mother tugs at the distance between preservation and capture and puts these impulses under a microscope.

In the book’s first section, the team in “An Uncontacted Tribe” observes by helicopter and through camera, “causing/minimal disturbance to the tribe/the government denies exists.” They watch the tribe, “awed because their bodies/light the jungle like red candles,” all this without contact—instead “the camera captures them.” Natural curiosity, without any equity or consent, becomes pointedly questionable. The book emphasizes a pervasive mammalian isolation that, turned clinical and procedural, begets dehumanization and erasure. In the sparse and heartbreaking poem “Dr. Harry Harlow’s Primate Laboratory,” the famous young monkey who chooses a cloth mother over the wire one with milk, says “Between/the two kinds of hunger/there can be no question.” The unhumaned becomes the most human: primate, invertebrate, mitochondria, woman.

Throughout Darwin’s Mother, there is a pattern of masculine imposition, a collective “we” that imposes their own categorizations and order on the world. The crew of scientists in “A Report From Our Team in the Field” strenuously reassemble pieces of bone into what is first called a monster and only later a her. These bones very likely belong to the famed Lucy discovered in the 1970s, several hundred fragments of bone fossils that comprise only 40% of a female hominin species skeleton. Our origin, uncovered from millions of years of dirt, incomplete. The scientists acknowledge that this “creature,” as they call their discovery, “did, in essence/give us birth,” but their superiority readily overtakes awe and respect: “we believe our race’s/ proportions to be superior both/ in function and form.” The voice in this poem is unsettling, a collective we that calls this collection of bones “far from generous”:

“she insists on holding

back from us, resisting our tools

and our innocent task that

will surely lend fame to her.

Each movement brings a little pain,

so she stiffens against the inevitable

disclosure, increasing her own difficulty

like any young, laboring mother.”

The darker nuances of excavation and collection are not exclusive to cis-men, but the tension of gender in Darwin’s Mother are clear. The men in this poem are in scientific pursuit and the woman whose bones they excavate is long, long dead but the violation here is palpable, the language of sexual violence distinct but employed with deft intelligence. The scientists, here and elsewhere in the book, are effortlessly condescending. Even a woman who proceeded them by millions of years is limited through language to the function of procreation. The mystery of these bones, however, resist much like their surface; whomever they belonged to may have never given birth, may not have even been a “woman,” for how can we in good faith impose our own constructed notions of gender on such a distant ancestor, whose conception of “her” body we can only try to imagine?

But of course we imagine, we project, in this human impulse to define and arrange. Again and again Darwin’s Mother smirks at these impulses. In “Material,” so much resists tidy coherence: “My soul has a trillion brittle wings…My soul’s parts know little/and don’t care whether I live or die./Its components make a mind outside of me,/hovering over the driveway.” The speaker’s soul is a menagerie of natural and artificial flora and fauna, a powerful force that sweeps over the archeologist’s brushes and shovels. A cell is as knowable as a daughter. A “loose copy of Earth” hangs suspended behind the speaker’s eye. Nordgern reminds us that our world “is vast but vanishingly small.”

Throughout Darwin’s Mother, the language is a “fragile egg” that “breathes a red and fluttering clot.” The poems surprise, pivot, maneuver from the wider lenses of science and history through an urgent microscope to lines that contain a primordial mourning carried in our living bones. Nordgren’s work challenges established hierarchies of naming and creation; “the inverse of my power/which came as cancer/And it whispered open your mouth.” The poems both speak from a specific, intimate I and function like a tray of glorious bones that, puzzled together, might suggest a whole.