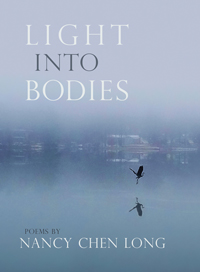

Review: LIGHT INTO BODIES by Nancy Chen Long

Review by SARAH LANDRY

“Light Into Bodies,” Nancy Chen Long’s debut full-length poetry collection, rests at the crux of occurrence and intention, of panicked flight and calculated design. Regardless of the reader’s instinctual approach to poems that exist in the context of one another, he or she will likely find that the first poem, “On Seeing a Heronry of Egrets Nesting in a Tree,” is the piece that defines the whole. As Long identifies the birds as individuals in an imagined scatterplot, she questions the validity of celebrating oneness and singularity when someone or something exists in a group. “Is that heresy?” she asks, and the poems that follow echo in an attempt to find an answer. Long’s imaginative glimpses of identity and identity construction fold across cultural and geographical space, and to peruse “Light Into Bodies” more than once is to visit a series of poems that continually redefine themselves to accommodate the author’s exploration of nature, memory, the body, and perspective, the four equally beautiful components of disproving any heresy.

Long’s use of memory is particularly stunning in the ways it manages to span multiple generations and multiple continents without ever leaving the scope of the her existence and capabilities. For instance, in “Christmas, Saigon” the reader is tugged between America and Vietnam on a line-by-line basis, occupying the eyes of both the father and his faraway daughter. In Vietnam the father watches a small child “not unlike / his own eight-year-old” struggle to secure a grenade to the wire mesh covering the window — and then the image shifts, delivering us to America and a photo, where “his own eight-year-old” is reaching to secure an ornament onto a tree. The deployment of Long’s father to Vietnam is the subject of multiple poems in the collection, but readers are also invited to experience further aspects of Long’s heritage with “A fine Chinese meal,” her mother’s story of being given away, as a child, to a man without children, and a grandfather’s insistences over the phone. It is ultimately Long’s voice and its ability to maintain a sort of narrative control that highlight her identity and her singularity in her multi-faceted lineage.

Although it may take the reader quite some time to realize that the “I,” the “she,” and the “you” of many separate poems are representative of a single entity, this, too, holds its own magic. Perhaps it is Long’s way of imposing a sort of optical illusion, a deceptive distance forced into being by how much room we believe there to be between ourselves and the subject in question. In “Hold on Lightly” there is a child “Running towards the school bus / [with] her blue-plaid satchel” while in “When We Finally Arrive Stateside” there is the “you” who “certainly won’t remember” the father’s departure overseas. And then, of course, there is a graduation to poems like “Murmuration,” where the “I” asserts itself and pulls over in a field to watch starlings zoom across the horizon. As readers we are given an opportunity to phase across life and experience, both near and far in our observations of identity, which inevitably matures.

Nature is ever-present in these pages as a suggestion and as an explicit fact, and Long allows nature to speak for itself and blend seamlessly with reality and identity. At times this is as complex as “Dugong,” which follows the manatee from the “delicate seagrass / that sways in an ocean meadow” to the speaker among them rippling into the sea and becoming strange shapes that are unrecognizable to their respective husbands. Here Long allows nature to provide a necessary obscurity, a blurred boundary between the identities the women understand and the identities their husbands perceive. Other poems like “She Tenders Her Faith with Cedar” offer a flowering of images that build on one another to create something far simpler: an identity shrouded in the beauty of spirituality and plants. “Cottonwood pollen” and “homiletic seedlings [of] / broadleaf, conifer, [and] coral” are simultaneously nuisances and proverbs that define where the woman is anchored and who she is alongside her ancestry and the “spectral drops of water.”

The “natural” aspects of Long’s work happen instinctively, but the physical and metaphorical body is given to us in more rigid glimpses and expressions that make us question whether or not identity can be pinned to anything physical. “The Importance of Shells” takes the bodies of mother and daughter piece by piece, describing “full-moon / faces, hair black / and hands quick” in a series of moments that balance individual identity with the “collective” of familial lineage. “Meditation—-Home as an Extension of Body” struggles with home and the body as varying objects and concepts that must overlap to be seen or understood. The “river running breathless” through the poem’s 14 lines suggests something fluid, an identity “absent of body” as it is washed into the flow, and we wonder what is left of the self when the water leaves it behind. Other parts of the body (and whole bodies) are mentioned throughout the collection’s three parts, and even when the images are fleeting they are just vivid enough to deliver Long’s desired message, musings on identity included.

“Light into Bodies” is certainly something to hold your breath over. To be startled to the surface of another person’s memories, histories, and perspectives is an enchanting feeling, and it is only with Long’s unique prompting that we depart from that surface and swim deeper, experiencing the quiet screams of identity that she captures. We may even find ourselves asking “which light?” and “which body?” and then reading through again to discover a set of poems that are familiar and yet wholly new. The key, of course, is that there is no definitive answer to either question. There are multiple lights and multiple bodies pervading Long’s work, and they are all worth reading into existence.