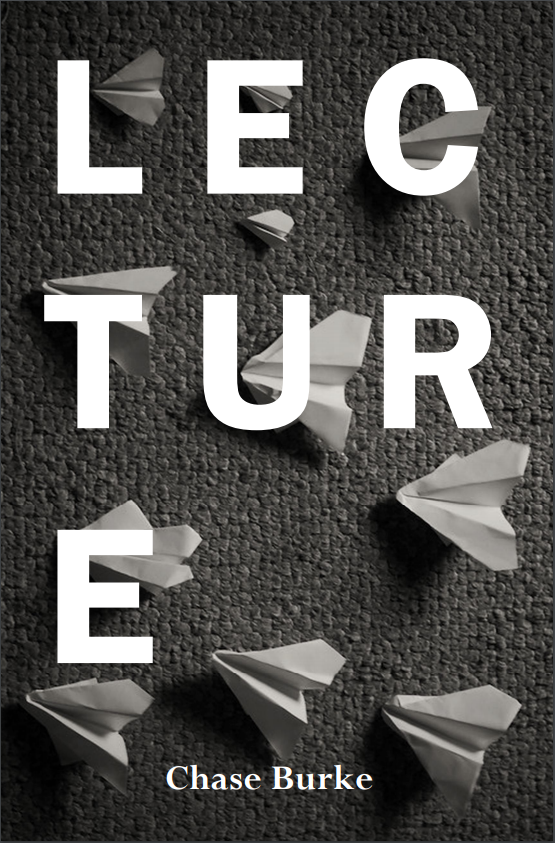

Review: LECTURE by Chase Burke

Review by Sandra Barnidge

If Chase Burke’s debut chapbook, Lecture, came with a quiz at the end, here would be the answers:

1. Julius Caesar drank from a blue cup, a very blue cup.

2. The greatest library in the world is probably in small-town Indiana.

3. Five thousand years ago, a man in the Alps ate ibex meat shortly before he was murdered with an arrow.

4. Moore’s Law has not stood the test of time.

5. A brother who drops a pistachio bag in the woods will not understand why this act distresses you.

Yet to zero in too closely on the quips and crystalline images of this set of 13 micro-fictions would risk over(under?)looking Burke’s wrestling with macro-issues of legacy, self-fulfillment, and the dis-ease of whiteness in America. In the vein of Lydia Davis, Kathy Fish, and Steve Almond, Burke’s fictions are heady, philosophical eruptions of nervous energy and counterfactual artifacts.

A common narratorial voice serves as the soundtrack of the collection, inhabiting a range of characters in tight spots, often literally: a submarine, a cardboard box house, a freezer, a library shed. These compressed settings are tight coil springs for narrative tension. “Under no circumstances should anyone look for the device I have hidden in the operating room of the submarine,” warns the narrator of The Submarine. “I saw a friend shred her fingers in the swiftly spinning blades of a garbage disposal,” offers the queasy protagonist of Finger Spell.

While a few stories within the chapbook are linked, most stand alone as thought-experimental forays into gentrification, mass-marketed art, and historiography, among other themes. “We both know this building is a maze, this whole city a puzzle, this entire country a safe without a key, and what’s the point of having a safe if you can’t get inside of it?” asks the everyman narrator of The Museum. “What is worth protecting if it’s inaccessible? An idea? A way of life? A memory? I don’t know, but then I’m not paid to know things.”

Burke’s fictions are at their best when they move out of the cerebral and into the push-pull of adoration and atonement within domestic relationships. In particular, the chapbook’s closing trio — But What Was In The Woods, Correspondence, and Restoration Efforts Underway — centers on a relationship between brothers that is distant and fraught, yet startlingly intimate. From Correspondence: “My memory of my brother will be a kind of reality, as will be his of me. Thinking will be making. Thinking will be being. And isn’t this what we want? To communicate without exchange? To know others the way we know ourselves? … It’s not hard to form connections, no, but no one ever talks about remembering them.”

This preoccupation with memory, of legacy and lasting-ness, is perhaps Lecture’s most consistent through-line. In Museum, Julius Caesar’s blue cup collects dust on a shelf as visitors gawk and muse, while a rocking chair creaks on a porch in Restoration Efforts Underway as a brother waits for a brother who will never come. Burke’s material juxtapositions beg the question of which “things” are truly vessels of memory and value in the long run. “It’s hard to feel good about yourself in the past, not when you know the results were unfavorable,” reads the opening of Alternate Ending. “Why commend what would be an inevitable undoing? Better to demand another opportunity.”

Throughout, Burke’s stories resist their easiest opportunities at punchlines, their most obvious key takeaways. Their endings do not resolve cleanly or cathartically; instead, Burke dangles variations of what if and what could be. Taken together, the fictions within Lecture form a whole larger than the sum of their spare parts — a (w)hole looming large as a brother, as immortal as a mountain mummy.

Class dismissed.