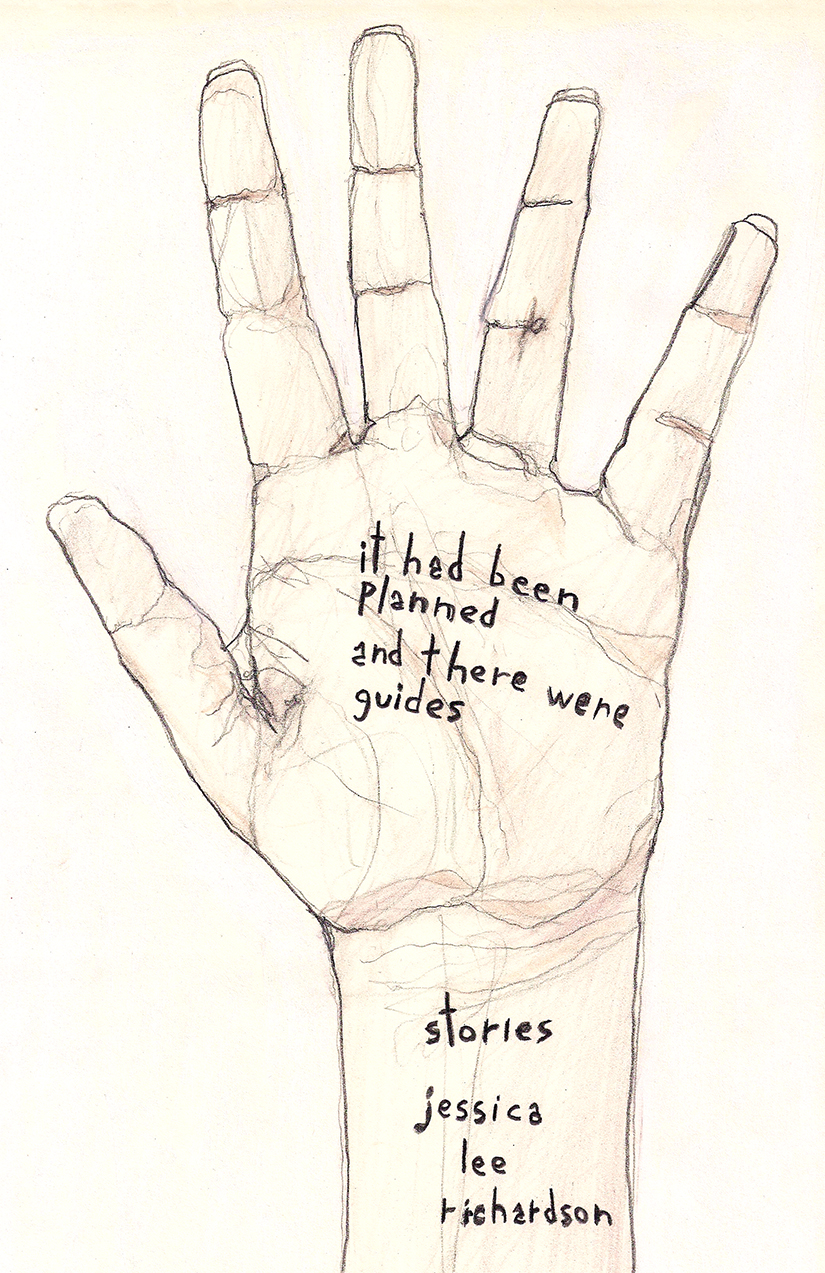

Review: IT HAD BEEN PLANNED AND THERE WERE GUIDES by Jessica Lee Richardson

Review by MEGHAN TEAR PLUMMER

Jessica Richardson’s first collection is as dexterously crafted as its content is deviant and feral. The collection gains its title from a line in the last story “Shush,” in which an unidentified group plunges over a waterfall in a concrete boat and survives, ending up amidst a flock of flamingos. If it sounds weird, it is, and Richardson is drawn to such weirdness, though in an older sense of the word, where its definition is “fatefulness.” Macbeth’s Weird Sisters are the Fates. And in It Had Been Planned and There Were Guides, Richardson plays all three.

Richardson writes in such a way that a colony of the most awkward animals on the planet are suddenly “kissing and licking feathers, biting themselves and each other, soft beaked. A flamboyance of pink necks, the letter ‘S’ multiplied….” Richardson imbues what-if scenarios with high stakes and poignancy. In speaking of the collection, it’s hard not to want to simply catalog the ground situations of Richardson’s stories, which are, again, wild enough to be entertaining simply in terms of their premises. Of course, this flattens the genius that not so much saturates Richardson’s writing as it does provide the scaffolding for her premises and execution.

Each piece in It Had Been Planned diverges from what comes before and after, except for “No, Go.” and “No, Go. Continued,” the two-part story that forms the hinge of the diptych into which Richardson has formed the collection: “Descent” forms the first half of this diptych, “Ascent” the latter, a decidedly hopeful configuration, or at least one that suggests redemption.

Every piece of text in the “No, Go”’s is an email interrupted with messages from a censoring software called NoGo, or a chat message from NoGo customer service reps. The story simulates the collapse of language, suggesting language is a bridge that can only take so much weight. Richardson traps the reader in a crossfire of rhetoric aimed at different parties: a husband’s at his wife who won’t share custody of their son; the same husband’s toward three different customer service reps; the wife’s toward the husband; and the messages the husband leaves for his son at the bottom of his messages to his wife. These last messages become increasingly disjointed and oddly punctuated so that the NoGo software can’t interrupt with its useless recommendations, like replacing the word “manipulating” with “managing, directing, controlling.” The result is messages to a young son that look like this:

B u t, M.I.K.E.Y?

In C)a)s)e

W e\are/separated-

Bever

Bever

Is this desig Nogo snag

know this: i.a.m.a.w.e.e.d.m.i.k.e.y.a.n.d.s.o.a.r.e.y.o.u….w.i.l.d.n.o.c.o.n.c.reet can

While “No, Go.” and “No, Go. Continued.” occupy a strange form for a common phenomenon (divorce), other stories describe strange phenomenon in plot structures that look suspiciously like Freytag’s pyramid. Take “Not the Problem,” a story of an old woman who takes an interest in a family of highly human spiders in her assisted-living apartment. A traditional plot arc and a third-person point-of-view combine to lure the reader into the belief that the story’s content and purpose will also be familiar and recognizable. But because “Not the Problem,” like most of Richardson’s stories, meditates on the ugliest kinds of love, and because such love is unpredictable, Richardson’s stories come off like magic tricks: you sense you’re about to witness something wild—the shape of the plot dictates it—though you can’t guess what that wild thing will be. The beginning of “Not the Problem” suggests the granddaughter who martyrs herself (not literally) to “care” for her grandmother will be the climactic catalyst, but that’s not the climax. The climax occurs when the grandmother’s anger prompts her to eat one of her spider friends—her very favorite one. With this action, Richardson shows how real love works: it’s as ugly as it is unexpected. It’s nearly the same with her plots: they are as inevitable as they are unexpected. The grandmother eats her favorite spider because the ones we love the most we bite the hardest.

The same dirty, unexpected love also shows up in the collection’s first story, “Call Me Silk,” in which the narrator’s thrill-seeking takes her to a homeless camp where she is attacked. Like “Not the Problem,” it’s possible to identify a mounting tension familiar to any Freytagian plot, but it is the chasm between the reader’s expectation and narrator’s reality that is so destabilizing.

“It wasn’t the first time I was raped,” the narrator tells us, “and I don’t want what I’m about to say to diminish how dark a crime it is to attack the nexus of intimacy. But this time I loved it. It wasn’t one of those fantasy come true situations—it’s dirty and wrong so it’s hot, like your groin is full of flaming pennies. It was heaven, ambrosia and harps, clouds turned to cream laced with cherries, whatever your image for heaven—this was mine, this rape. …‘I love you I love you I love you,’ I rattled in spats. …I don’t care what you call me…because I dropped through that trap door at the bottom and came out on top. Power is circle we oval so vertical it appears line thin.”

The climaxes (plot-related and otherwise) of It Had Been Planned surprise even the most veteran reader, though Richardson balances such spontaneity with believability. Who could have predicted that the way the narrator in “Call Me Silk” would “win” her rape was through loving her attacker, though by the end the story, the scales have fallen from our eyes and we see the narrator’s love is inevitable and powerful and ugly.

And most of Richardson’s stories deal with ugly love. In an era of irony and deflection, I acknowledge that this is a dangerous claim. But I would also claim that irony and deflection are being killed off, hallelujah, thanks to New Sincerity and probings into the word “sentiment” and also writers like Richardson, whose battle-axe in the war against normal is earnestness.

There’s an anecdote Carl Wilson relays in his 33 1/3 book What We Talk About When We Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste, which is about Celine Dion’s music. He tells of how Elliot Smith met Dion at the 1998 Academy Awards, and how she was so kind to him before his performance, so earnest, that Smith had to admit “she was too human to be dismissed.”

Richardson’s stories are too human to be dismissed, too human to require much suspension of disbelief, even if she is writing about preening flamingoes or a family of spiders or a box full of exotic animals that can be killed and revived at the whim of the little girl who receives them as a gift.

For the stingier reader, who remains unconvinced of sentiment, behold the Other, whose presence in her stories is about as ubiquitous as that of dirty love. Richardson finds a way to write convincingly about the chronology of environmental, labor, and family laws, and also the scientific invention of a body suit that protects swimmers from the jaws of the beasts they will almost certainly encounter. She has a new master carpenter creating doors and cabinets and even place settings with detail so fine, it seems she derives her content from past lives, years of personal experience and expertise.

It Had Been Planned’s population would shine in any diversity index, and, in the same way Richardson rescues love from triteness, so does she write with the compassion and detail necessary to pull off a likely encounter with otherness. At the same time, the collection shrugs off political benchmarks for diversity and narrows its focus to the micro-level of emotion, leaving the reader transfixed by humanity instead of shrinking back from an agenda.

In “Check and Chase,” eponymous child twins believe their house eats their toys. Richardson leaves a breadcrumb trail up to the belief that the twins’ druggy mother has been selling their toys for the product she craves. But then out of the ether comes this: “The house wondered why the kids were such pussies. It felt it deserved competitors of greater merit. These kids were practically feeding it their toys…. The house searched itself for something that would be properly missed.”

There’s magic at work here. Richardson paints a specific picture of this family: a mother who’s sleeping if she’s not doping; young kids who are in charge of feeding their even younger brother; “hope of a stepfather with his own DS system”; crap uselessly stockpiled amid shitty furniture; toys “distributed by Charity Santa”; Check’s “cheek, which was darker than hers [Chase], the color of cardboard in the rain.” There are a million familiar places this story could go, and again, we think we recognize the trail. But the magic comes with Richardson’s pulling the house’s sentience out of nowhere, a rabbit out of a hat. Such a switcheroo not only allows for the kids to be labeled “pussies”—is there anything more politically incorrect?—but it also validates and literalizes their belief, however rife with child-logic, that the house stands against them. To describe this move in terms of pop-culture lexicon, Richardson leaves it right there, allowing the reader to deduce analogs to poverty or test the textures of the kids’ rough world.

The already-mentioned “Call Me Silk,” the first story in the collection, and perhaps its keystone, similarly shunts aside political expectation. For all the politics that could be brought to bear on its events—rape, gender dynamics, self-sabotage—“Call Me Silk” is also about extreme sports, a simpler but no-less interesting premise that allows the story to be read for entertainment as much as intellect, in the same way that Shakespeare’s plays reward a scholarly analysis and a scatological sense of humor. Richardson’s collection is Carnival: expectation is turned on its head, though no topic or emotion is too dark or sacred to be left behind.