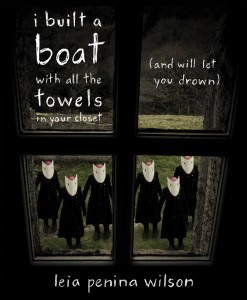

Review: i built a boat with all the towels in your closet… by Leia Penina Wilson

i built a boat with all the towels in your closet (and will let you drown)

Leia Penina Wilson

2014

112 pages

Review by RYAN BOLLENBACH

The universe of Leia Penina Wilson’s debut poetry collection i built a boat with all the towels in your closet (and will let you drown) is rendered through six separate sections from multiple perspectives: a first person speaker, and male and female characters who appear in the third person. Through the varying amounts of access these perspectives afford, Wilson questions the relationship between the appearance of these characters to themselves and to others. The various ways Wilson navigates these appearances (physically, through her use of image, or linguistically, through the often complex thought processes of her speakers) she interrogates the generative relationship between linguistic and physical modes of understanding: the external interpreted internally, the internal shaping perceptions of the external. The wide scope of how the characters in this book react to their experiences are what makes reading and re-reading this book so gratifying.

Wilson begins creating this range in the first line of the first poem in the volume I am looking for something to keep me warm in the winter / when the sky lets loose snow and all its other feelings through the speaker’s description of the city:

i have found a city. a solid hydrodynamic sphere / with mailboxes and daylight and stampedes of regular

people who want to be in love.

This description of the world as “a solid hydrodynamic sphere,” like a schematic, gives a perimeter to the city the “people who want to be in love” inhabit. The phrase also uses the language of scientific inquiry, a technique Wilson’s often employs in this poem (“hydrodynamic sphere,” “stampedes of regular people”) and many of the other poems in the manuscript.

Later in the poem, the concepts of “vectors” and “mapping” come into play. These verbs usefully suggest what Wilson’s poems record: a map of the collisions of her character’s vectors.

Wilson maps of these residuals through her careful molding of her characters’ inner dialogue, most apparent in poems in the first person perspective, as in this line from her poem in the academy where the speaker stumbles over one of the many tensions of the book: “then the private became confusing or I was confused by it / and couldn’t tell the differences in grammar.” This character’s understanding of interpersonal confusion, identifying it as grammatical confusion in and of itself, and the lack of punctuation in these lines which textually represent this confusion are emblematic of the subtle linguistic playfulness that pervades these poems.

In the prose poem & prepositional phrases, which comes roughly half way through the collection, these “differences in grammar” cause an argument when Wilson’s female subject is accosted by her lover. He protests “I thought you loved me. I love you.” and she is alarmed: “he looks earnest/sad/hurt. his humanness bewilders her—she panics and tries her best to hurt him.” She is successful: “he hurts,” Wilson writes, “he hurts more.”

This exchange—like others in the volume—explores the divisiveness of imprecision, and panic felt in misinterpretation. The argument results in “an erotic residue” on the floor, the “horror” of which “dismantles” the speaker. Wilson ends the poem building even more tension, leaving the woman’s anxiety lingering, punctuated with a period rather than a question mark: “how will it ever become clean again.” For Wilson’s speakers, a reality without dissonance is not in sight.

Moments where the focus shifts to the first person add still more dynamism to Wilson’s map. Her lyric voice in this collection often dramatizes the speaker’s reading of herself. For example, in in fact it is muscle the first person speaker pretends to be a fish:

i pretend to be a fish and aren’t floppy enough.

i’m un-correct and pretentious.

& I emit.

Wilson begins this poem using “un-correct” syntax to mirror the speaker’s labeling of her own logic as “un-correct,” anticipating (and necessarily miming) criticism directed at the speaker’s question “how do fish do this…” She writes her frustration out on a napkin never meant to be read. Later in the same poem, Wilson exemplifies how deftly she can complicate these self-comparisons in the speaker’s use of the verb “emit.” “Emit” suggests brightness and lucidity in the speaker’s comparison of herself to a fish that troubles her anxiety that this strand of thinking is “un-correct.”

Later in the poem, the speaker factors in her understanding of fish on a biological level, reflecting that fishes’ “floppiness is in fact muscle.” The tension between these two understandings of how fish relate to the speaker, not to mention the creativity it takes to analogize the self in terms of a fish to begin with, is an impressive example of Wilson’s ability to maintain multiple ideas in her poems at the same time.

But, we are reminded in the end of the poem that, for Wilson’s speakers, her intellectual flexibility isn’t enough to arrange the clutter of relation. Here, the speaker laments her stasis, her emotional “un-correctness,” in an intimate moment with a lover:

he cried and i watched that too. i record on a napkin too i am unable.

i pretend to be something else pretend to be.

In her prepossessing posture, “a wife and mother” transforms into “a small museum / holding lots of small collectables / wondering about the costs of things” only to be labeled “too wide,” only to ventriloquize the darkness with anxiety over the size of her body “you’re not / going to fit through that hole.”

Wilson’s other speakers internalize criticisms of the body as well. Wilson’s speakers, however, dissect such thoughts for their constituent parts. Late in her prepossessing posture, the same speaker asserts in no uncertain terms that “she,” in the denotative and connotative senses, is merely a “system of value.” The residual of moments like this is her character’s exploration of the valley between feeling shame (in this case, over the body) and understanding (being critical of) the value system that informs such shame.

If, as Dan-Beachy Quick says, Wilson’s subjects “suffer the intricate mystifications of their own inquiry”—if there is no solution that mends the dissonant relations between the people in these poems—then the most rewarding quality of this volume is the extreme, definitively painstaking, detail with which Wilson navigates this mystery. Wilson’s ability to write the difficult difficulty gives her poems urgency. It is the navigation (successful or not) of this difficulty which leaves readers with a better understanding of the weight of interaction, what it means to be colliding and making vectors in a “solid hydrodynamic sphere.”