Review: FROM OLD NOTEBOOKS by Evan Lavender-Smith

Review by STEPHEN THOMAS

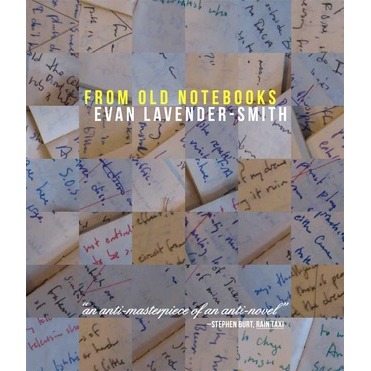

Evan Lavender-Smith’s From Old Notebooks is a conceptual book that would like to think it’s hiding a living, breathing, narrative heart; and it basically is, I think. F.O.N presents as a collection of snippets: ideas and memories (“The anxiety I felt as a teenager about not having enough wet dreams, an anxiety I sometimes still feel”), notes for stories and plays and works of conceptual art (“Short story about a church on the ocean floor. Congregation in scuba gear”), and bits of dialog overheard and imagined, all ostensibly culled from the author’s old notebooks, several of which are apparently featured on the book’s cover photograph.

If it were just a bunch of random snippets, the experience of reading From Old Notebooks wouldn’t be much different from reading a dead author’s old papers and letters. However, like some other recent and semi-recent faux-random narratives like Matias Viegener’s 2500 Random Things About Me Too, Harmony Korine’s A Crack-Up at the Race Riots, Édouard Levé’s Autoportrait, or any of David Markson’s books (which Lavender-Smith mentions several times—he likes Markson a lot), F.O.N has a latent structure that serves as one of the book’s central mysteries. Within the first twenty or so pages, as it becomes increasingly clear that new entries are being written expressly for the book, the “just a bunch of old scribblings” conceit starts to fall away, and we realize we’re in something a little more complicated: a book trying to figure itself out. And as entries like “Using the occasion of F.O.N. To catalog all my problems” and

From Old Notebooks: A Novel: An Essay

From Old Notebooks: An Essay: A Novel

start to appear, we realize a meditation on ‘form’ is perhaps a central theme, or form, or process, of the book.

It’s a serious book, then. It’s not a light read. It’s a demonstration of an author trying to merge with his own work; a large percentage of the time the vibe is somewhere in the delta triangulated by ‘super-serious Frankfurt School-style philosophy of culture’, ‘deadly-serious Thomas Wolfe-style contemplation of own soul’, and ‘Hugh Kenner-level James Joyce scholarship’. “For the theoretical physicist of this century, the hypothesis of infinite time should at once contain and not contain God” is an example of a thing that is said in this book.

And yes, it’s at times boring, and it’s at times obnoxious. Sometimes I want to shake Lavender-Smith for his abstruseness, and as someone with a similar education (philosophy and literature concentrations in college) and reading interests (Hofstadter, Joyce, Wallace, Wittgenstein, etc), I get his references. I’m the target audience for this book.

But at its best, From Old Notebooks offers a glimpse into someone else’s inner life that’s more intimate than the polished surface of unbroken narrative prose (or verse, for that matter) can hope to offer.

And it does something else, too. As someone who spends a lot of time on the internet getting instant gratification from social media, for me the super-serious atmosphere of a lot of this book functions as a reminder of a feeling, and maybe even a concomitant lifestyle, which I feel is incompatible with the internet. This book is kind of like that scene in Miranda July’s The Future where she hides all her electronics, but a demonstration of what would happen if you did that for however long it takes to write a book. The result is a pretty convincing impression having been created that Lavender-Smith has gone to this place inside himself where he’s brought every ounce of analytical and artistic artillery to bear on figuring out who the hell he is.

So: if this is the quest, what does he find?

Well, I’d argue that Lavender-Smith finds what’s important to himself, and what’s important to Evan Lavender-Smith is, as follows, in order of most to least important:

- Evan Lavender-Smith’s ideas for works of art

- his ideas about other people’s works of art and philosophies (tied for prevalence about equally with supra)

- thoughts on and feelings about his wife, son, and daughter

- the conflict between energy expended on family vs. energy expended on art

- jokes and observations on art, writing, and philosophy

- worries and pretty lines about death

- insecurities re masculinity & re being a person

- reflections on the mechanics of contemporary American writers’ career-building

- notes on the relationship between drugs and writing

- thoughts on Ulysses

You could say that what he finds is an ego, a consciousness, and a guilt—the aspects of himself through which all else is refracted.

Of course, it took a while to write this book, and so as we follow the journey of its writing, which, edits notwithstanding, appears to have been done more or less from beginning to end, we also get to see Lavender-Smith discovering aspects of himself. In particular, we see him coming to terms with the life he really lives, which is always there when he comes down off his high-minded conjectural cloud. And in the life he really lives, we see him find—brace yourself for the Disney aperçu—his family: his wife Carmen, his daughter Sofia, and his son Jackson.

One of Lavender-Smith’s strengths as a writer is his willingness to admit weakness, folly, dickishness, and that’s never more fraught than with his family and close friends. “I hardly notice Sequoia until Carmen and the kids are out of town, but once they’re gone I expect her to go back to being my very best friend, as it was between us before I met Carmen,” he writes. I get that, and I think it’s moments like these (and not his latter-day Nietzscheizing!) where the book’s best insights are discovered and communicated.

The way Lavender-Smith’s family emerges into the book is compelling, too. In the first thirty or so pages, their names start to appear, completely unexplained, in little anecdotes and bits of dialogue. Gradually, we piece together who’s who, and the relationship thus revealed between the narrator’s life (on one hand) and his thoughts (on the other) begins to inform and deepen our understanding of both.

My favorite moment of the book, for this reason, is this anecdote, in which we see the self-styled Great Thinker as he appears to others IRL:

The most acute sense of embarrassment I have felt in recent years occurred when I came upon two people at a party whom I thought I had just then overheard whispering something about me, and I asked them to reveal what it was they had been saying, and they playfully insisted that they were not talking about me, but I was sure that they had been so I persisted in my demand to know what it was they had been saying, and they continued to playfully insist I was mistaken, and I continued to persist in my demand to know, and this exchange continued and continued until it became very uncomfortable, upon which time one of them emphatically declared, We were not talking about you, Evan! Get over it!”

But if Lavender-Smith, by writing this book, and we the reader, by reading the book, come to gain a greater understanding of who Evan Lavender-Smith is, how does the book feel about the book? A strange question to ask, maybe, but I feel like, the mystery of ELS’s psychology aside, the book’s counterpunctual theme is: what is From Old Notebooks? Therefore, the book, I feel, has to demonstrate its understanding of itself by arriving at an appropriate ending, which, just maybe, will retroactively define the ever-shifting ambiguity that is the book’s form from the beginning.

So how does this crazy meta-drama play out? Well, on one hand, pretty elegantly, I’d say. One of the two main sources of the book’s dramatic tension is the writer/narrator’s feeling of being caught between thinker and artist, and that drama gets resolved almost Hofstadterianly elegantly somewhere around the line “Joy, rather than error, is the better antonym to truth.” I don’t think it’s giving too much away to say that, at least on my reading, by the time we get to the line “To be led by beauty, not truth,” the writer/narrator, like his hero James Joyce’s self-hero in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, has fully committed to a conception of himself as an artist. And with that, the book retroactively becomes the creation myth of its artist-creator, and pops out of the toaster as a classic Künstlerroman.

Unlike Stephen Dedalus, however, Evan Lavender-Smith has a wife and two young children, and thus the book’s other source of dramatic tension—the writer/narrator’s relation to his family—is more fraught. The last page of the book contains a few snippets that indicate, maayybe, a longed-for sense of work/life balance: there’s “Story about husband and father of two who sells his ass on the street to make ends meet”; a sweet mini-dialogue with one of his kids; and a nice image of a Christmas tree. And since the book seems to operate on a proportion-as-value principle, the fact that four out of the seven of the snippets on the last page are familyish or familial is maybe as close as From Old Notebooks comes to offering us a shiny apple of an answer re the ‘life’ problem. Compared to the elegance of the solution to the formal problem, though, this answer is pretty hand-wavy, which unfortunately affirms what I think a few of us already suspect, which is that, hard as it is to figure out how to write a book, it’s maybe even harder to figure out how to live.