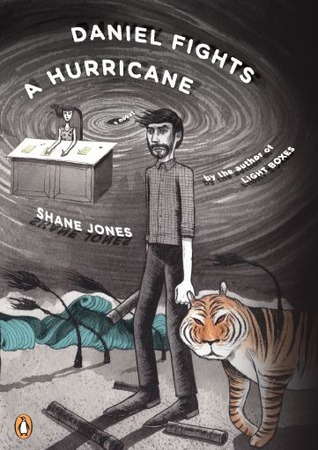

Review: DANIEL FIGHTS A HURRICANE by Shane Jones

Review by ERIN L. MILLER

The unfolding of Shane Jones’s newest novel Daniel Fights a Hurricane ultimately hinges on fear—specifically, protagonist Daniel Suppleton’s fear of a hurricane wiping out the town. Suppleton creates an internal world that stems from a colony of deep anxieties, self-doubt, and a too-active imagination. As a result, he becomes so consumed with dread that his life rapidly deteriorates, and while in his dreamscape, the hurricane becomes a physical thing to defeat.

Written in sections, the story jumps from the illusory world to the real one, moving back and forth from Daniel’s and his ex-wife Karen’s perspectives. The writing style is a simple, straightforward, hip kind of surrealism, akin to other current fantastical writers like Aimee Bender or Karen Russell. The tone is often cavalier, at times dipping into an overly playful ironic voice—but this all lends to the overall atmosphere of the book. A novel that exists more so in the imagined world than the real one, it isn’t difficult to approach the text as a sort of dream journal or epic poem than as a work of fiction. Even the writing style reflects the matter-of-fact quality of dreams—everything is given plainly, the writing often giving way to repetition, and you simply don’t question any of it.

Despite being a book centered on personal anxiety, Daniel Fights a Hurricane could also be designated as a sad love story. Readers are first introduced to Karen as Daniel’s unofficial therapist. He admits to staying up all night, “thinking about what’s real and what isn’t” and being unable to tell the difference between the two, which is one of the central factors to the undoing of their marriage. As the book goes on, we learn more about their strained relationship through brief periodic flashbacks. As the main character of Jones’s first novel Light Boxes has been characterized as someone plagued by the worries of a writer, Daniel also seems to mock the distressed writer’s lifestyle. But the book is more than an extended allegory for a novelist’s woes. It’s also a story about the quandaries of love, or perhaps more acutely, the ways in which exaggerated self-worry can interfere with sustaining a relationship.

Outside of this relationship, readers follow Daniel’s efforts to build a large line of connected pipes to bring ocean water to a town in drought—before the hurricane hits. Helping him are characters such as Iamso, a boy who writes what everyone is feeling in the form of poems; Peter, the world’s most beautiful man with the world’s worst teeth; the two-second dreamer, a man who can show people two-second dreams by whispering them into their ears; Oliver, the man with tattoos; and Helena, the woman Daniel believes to be his second wife.

Every character in the novel has a different definition of what the hurricane represents, just every individual has different interpretations of personal fears. By focusing on the word “hurricane” (I didn’t collect a total count but Jones uses the word generously), Jones directs our attention to the central idea of fear. Although, in an mélange of surrealist details that seem to lack a universal thread at times, the reader might question the aim of it all. Probably the best indication of what this mixed bag of components represents is described early on in Daniel’s journey. Peter brings Daniel and Iamso to a cave in which he shows them a series of connected rusty pipes that together make an intricate box. When a wheel on the cave wall is turned, water flows through the pipes, creating the lovely and strange effect of vibrating veins. Captivated, Daniel asks, “What’s the point of this?” to which Peter responds:

“I don’t know… I just think it’s beautiful… It’s beautiful, and that’s all there is to it.”

Like the messy mental processes that coincide with fear, the book is also sort of disheveled—while still maintaining its allure. By the end of the novel, I found myself wishing for a few more tied strings but, then again, Jones doesn’t seem concerned with that sort of sense. This isn’t a book about a man with mental illness, or even a book with an overlying moral, but rather one about the journey a man takes through his own mind and the painfully human attributes that motor his experiences. And we eventually find that his fears hold some unexpected truth.