Review: A Trail Guide to RESERVOIR by Taneum Bambrick

Review by Emily Montgomery

- Bring this book to your nearest natural area. A national forest, a city park. A local lake. Look around. Find a bench to sit on for a little while. Enjoy a moment with the songs of the marsh birds, or the quiet under the pine canopy. Open now to the cover page. Did you know that here in Alabama, similar to many other states, there are no natural large lakes? They are all reservoirs, the results of dammed-up rivers. Many of these natural spaces we take for granted are not so natural, and they can only maintain that facade due to the behind-the-scenes diligence of hard-working employees who water the plants, manicure the trails, and clean up what we park-goers leave behind.

I become a part of this garbage crew

empty cans along

the Wanapum pool.

Peel condoms off rock

beside fire pits—

call them snakeskins.

I learn quick.

—“Litter”

- Eye the nearest trash receptacle—odds are high there’s one close by. Who are the people who keep this space clean? In this chapbook, Taneum Bambrick gives us a glimpse. Turn to the first poems of the book and enter this fictionalized account of her time picking up litter and hauling trash out of just such an open space. Here she brings us onto the garbage trucks, beside the dumpsters, and in the waters of the reservoirs of two dams in Washington State. Through these poems the narrator, a young woman, struggles to integrate into the crew of older men who have spent their lives doing physically demanding jobs. She is the outsider here, due to her stature, her age, and her gender—made most clear by the sexism she experiences from her coworkers.

None of it’s you, really. Just you in this place.

— “Gaps”

- Environmental theorists still struggle to pinpoint the concept of wilderness, what it can and cannot include, though most definitions dance around the idea of a space without human influence—whether or not any of these places exist. The reservoirs that Bambrick paint for us surely cannot be considered wild, as they are man-made constructions, but they still straddle the idea of wilderness through their mimicry of a natural place. Similarly, we see the narrator of this collection struggle to find her place within this setting, this group of people. She pushes boundaries and crosses lines the way the landscape does, the way a river might carve curves into its course.

I knew I loved Park with fish blood on his hands. The way he smelled like fish

blood and smoke. Park was my boss so we never rode in the same truck even

when he loved her he loved me so I sat with Ray.

—“The rock man”

- Turn the page and look up, look around you: notice the others with whom you are sharing this space. Families, runners, hunters? What are their relationships with this space, and with each other? These blurred lines between natural and man-made also house the blurred intersection of person and place, and of person and group. We see in Bambrick’s poems the complications within these interactions, both the successes and the failings. We see the tension between worker and self, perhaps especially in the moments the narrator must handle dying or dead animals, and injured or dead people—and how her coworkers then handle her.

When I cried it made them comfortable like I could be

a daughter, wife, or something they knew how to see.

—“Biological control task”

- Take a break from reading and flip through the pages to learn the ecosystem of this book. The first poems are built of shorter lines packed together like soil. Then they evolve to longer prose pieces, like rows of long grass becoming a field. Then again shorter phrases, sparse on the page, that wander like water moving through a stream. Think of the worlds inside this book, which scopes hunters and hunted, flora and fauna, love outside of the accepted and expected, understanding of others and of self. Draw a map. Chart the trails. Find the graves—marked and unmarked. Purposeful and happenstance. There are many.

We dropped the box in a shallow hole.

Covered damp dirt with gravel. Projecting

what the family would have wanted,

we said a few words. Unclipped and hung nearby

his heart-shaped tag. Jim was a dad, he knew

to set a flowery weed. Those were the ways

he made work light for me. Said if someone were here

with his daughter—standing by the flat

water, old blood on her baseball hat—

he would want him to tell her not to come back.

—“Grave by the Lake”

- Close the book, close your eyes. Open them again. Get dirty, and then get clean. Dirty something, then clean it. Put the book away, then pull it out again. Read it, and re-read it.

When the dam cracked I

stood beside it

isn’t just the dam

I said

—“Landscape, comparison”

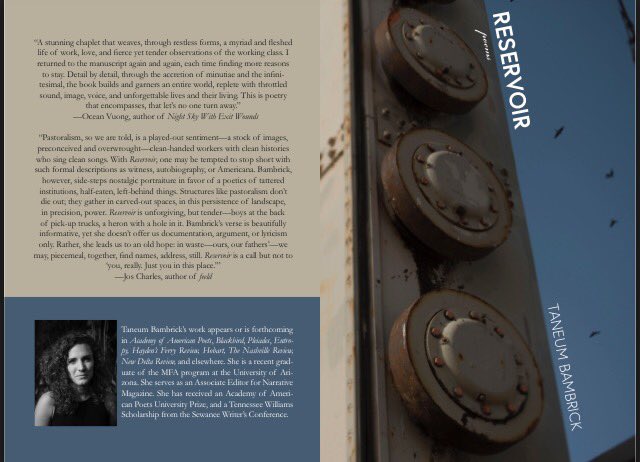

Taneum Bambrick’s poetry collection Vantage, of which Reservoir is an excerpt, was recently selected by Sharon Olds for the 2019 APR/Honickman First Book Prize. Vantage will be published in September and distributed by Copper Canyon Press.

Reservoir can be purchased here