Reva Speaks a New Dialect

by Shastri Akella

BWR 2024 Fiction Contest Runner-up

Reva doesn’t get a bridal welcome: she hears neither shehnai nor danka when her palanquin is lowered in front of her husband’s house, and when she steps out, in place of a group of women showering her with marigold petals as they break into ‘Pellikuturu’, she sees a solitary figure standing quietly next to the door, a stranger who, like all the widows Reva has known, wears a white sari and keeps her head shorn. She beckons Reva over and introduces herself as Kaveri, her sister-in-law. Then, with a hand to Reva’s back, she announces, “She’s here.”

Their father-in-law, who’s sitting in the living room, perched on the edge of a recliner, regards them with a sour expression reserved for unseasonal rains. He raises one hand. His sagging upper arm flesh quivers as he points to a turmeric-dotted brass pot placed on the threshold, filled to the brim with raw rice-grains.

“Kick,” he says.

Reva kicks, but not gently, as she’s supposed to, as scripture prescribes. She spent nine hours cooped up in the palanquin. Her feet welcome the prospect of some action. With a sprightly kick she sends the pot flying across the drawing hall, over her father-in-law’s head. It pitches against a wall of framed family portraits but leaves them unharmed. It falls with a dull thud. Kaveri bursts out laughing.

“I wanted a wife for my boy,” he says. “Not a football player.”

Kaveri’s laughter ceases abruptly. Their father-in-law groans as he gets to his feet and shuffles away.

Gesturing to the wall of framed photos, Kaveri asks, “You want to see him?”

Reva doesn’t know what her husband looks like. Her mother met his father, dowry changed hands, the marriage date was fixed. At their wedding, they wore marigold headdresses that concealed their faces and he left right after to attend to his tea estate.

“The day he returns I’ll know anyway,” Reva says. “Until then, let a girl dream.”

“What’s he like, this Dream Boy of yours?” Kaveri asks as they walk down a hallway.

“He’s got kind eyes, but with a hint of mischief to them,” Reva says. “And a smile that’s sweet but also knows how to tease when the time’s right.”

Kaveri laughs. “All right. I’ll let a girl dream.”

They enter a room with bare, uneven white walls, a bed, and no other furniture or adornment. A boy joins them. Kaveri introduces him as her eight-year-old son. Prashu. Neither mother nor son were present at her wedding because, Reva knows, widows aren’t allowed to attend.

“That was amazing,” Prashu says, mimicking a kick. “How old are you?”

“Rude!” Kaveri exclaims.

“She knows my age, why can’t I know hers?” Prashu demands.

“Fair point,” Reva replies. “I’m sixteen.”

Kaveri’s face breaks into a mixture of surprise and anger.

“You sound different,” Prashu observes.

“She speaks the costal Andhra dialect of Telugu,” Kaveri says. “Not our Rayalaseema Telugu.”

“You’re older than you look,” Prashu says. “But I’ll let you play with me.”

“Such kindness,” Reva says.

Mother and son sit on the bed and they continue talking. Kaveri fans her face with the edge of her sari. Reva takes off what little jewelry she’s worn—glass bangles, earrings and nose-ring, both made of copper. The wedding band she keeps. The day before the ceremony, Reva remembers, Amma had taken it off her finger and pressed it into Reva’s palm. Prashu brings them glasses of water. Reva swallows it in greedy gulps and realizes she’s parched.

“We store water in an earthen pot,” he says, “and sprinkle vetiver blades over on top.”

He beams, delighted to educate a grown-up.

“Is that why it’s cool and tasty?” Reva asks, playing along, her eyes wide with wonder.

Prashu responds with a vigorous nod.

At about five, the tropical heat is alleviated somewhat by a cool September breeze that’s infused with the smell of eucalyptus.

***

Reva decided to ask for a gift on her eighth birthday. She spread her blanket on the floor, lay down, and kept herself awake by humming Vijayashanti film songs. She fell quiet when she heard the door: opened, closed. The old spring mattress groaned when Amma sat on it. The smell of hay filled the room. Reva cleared her throat.

“Yes?” Amma asked in the dark.

Reva felt cold. She heard the rustle of the notes that Amma tucked under her pillow.

Reva said, “If Nana was here, he’d buy me a birthday present.”

“You know what the village men say?” Amma asked. “Your Nana took one look at you and fled because you look like a piśāci.”

Piśāci. Witch.

“That hurt?” Amma asked.

Reva gulped and nodded. Her hair scratched audibly against her pillow.

“I’ll tell you every night,” Amma said. “One day it’ll stop hurting.”

It became Reva’s bedtime story. If she was asleep by the time Amma got home, she was woken up to listen to what the men of Dandi had to say: about Reva’s dark skin, her mother’s sob story face, the bad luck they deserved. One night, Amma introduced her to a swear word, a coarser synonym of ‘penis’. Modda.

“They ask me to say it, and when I do, they shame me,” she said. “But I decided it’s just another word. A string of sounds and letters. So their shame doesn’t touch me.”

Why do they ask you to say it? Reva didn’t ask. When Amma left home the next night, Reva followed her. Their dark, empty street smelled of stagnant water. The furry bodies of alley cats brushed against her bare ankles as they made their way towards the dustbin.

Reva crouched behind a bullock cart, parked on the street corner, and watched. Amma entered the village square where men sat on stools set under a banyan and sucked on a communal hubble-bubble. They clicked their tongues and shook their heads when Amma walked past them. Then, one of them got up and followed her into the night.

***

Reva and Kaveri fall into a rhythm of domestic labor. Kaveri begins chores, Reva finishes them: Kaveri washes the clothes, Reva dries and folds them; Kaveri cuts vegetables, Reva turns them to curries; Kaveri sweeps the floor, Reva mops it; Kaveri warms eucalyptus oil, Reva rubs it into her father-in-law’s swollen feet.

On the night of the new moon Kaveri whisks Reva out of the dark house, into the dark night. The lantern sways. Its flame flutters. Light and darkness play Chase on the road.

They cross a small bridge. Sindhu’s Swing. Kaveri supplies its name. Under its curved wooden spine flows the Krishna River. Quiet, unlike the Godavari that roared underneath Yamuna’s Arrow, the spindly timber bridge that swayed like a cradle when the palanquin bearers who carried Reva away from her mother’s home scaled its length.

They enter the cemetery. The urns, buried neck-deep in the ground, are unmarked and look alike. Kaveri leaves a hibiscus on the mouth of one urn and says a prayer.

“How do you recognize your husband’s urn?” Reva asks when Kaveri is done.

“My mava’s urn smells of him,” Kaveri says, concealing her grin with four fingers.

“Girl, you’re weird,” Reva says.

“Says the girl who won’t see her husband’s face to keep Dream Boy alive,” Kaveri says.

Together they laugh. They fall quiet when they hear a song. They can’t make out the words but the voice—husky, old—is distinct. Just beyond the cemetery’s periphery are the orange orbs of torches, gathered in a circle. The voice soars into what feels like its crescendo.

“It’s the Madigas,” Kaveri says, her chin awash in the unwavering flame of the lantern. “They used to have their huts on our side of Sindhu’s Swing. But the panchayat that got elected last year moved them here because they decided out of the blue that they no longer wanted untouchables drinking from the same side of the river as the rest of us.”

Did Nana sing, Reva wonders: when he was alone, when he was with Amma, inside the safety of their hut?

“Sixteen,” Kaveri says. “You’re a child.”

“They didn’t tell you?” Reva asks.

“That’ll be the day—when widows are treated like family members,” Kaveri says. “Prashu is the only reason I’m home. If I was childless or had a girl they would’ve packed me off to a widow ashram.”

The song fades into its low notes. The silence that follows feels freshly-washed, a thing Reva wants to curl under and fall asleep.

***

Over time, Amma’s stories stopped hurting. One night, Reva said, “Do you have to do this every night? It’s so boring.”

“They say the same old thing,” Amma conceded.

“Let’s give them ideas,” Reva said.

“Like?”

“They could call you Senior Citizen Piśāci.”

“Careful there! But okay. That’s clever.”

They didn’t laugh, but whenever Reva recollected the moment, she could’ve sworn that the distinct duet of their laughter peppered their conversation.

“Now that it stopped hurting, let’s talk about the other Senior Citizen Piśāci,” Amma said. “Your Nana.”

Reva felt the muscles in her back turn taut.

After her parents got married, Reva learned, Nana routinely came home injured: skinned knee, chipped tooth, dislocated shoulder. The handiwork of men who now followed Amma into the night. Priests who doubled as god’s bouncers, in control of who could entered the temple and who couldn’t. Panchayat men who made the law, held court, served the sentence. Landlords who gave out loans at impossible interests.

“They wouldn’t touch him except to beat him,” Amma said.

“Why did they beat him?” Reva asked.

“Because he married me,” Amma said. “He was eating up the caste chain—their words.”

“When did they stop?”

“They didn’t.”

Reva turned in the dark to face Amma.

“We tried running away after we got married. But they caught us and brought us before the panchayat. I fully expected an honor killing.

“But they spoke about our housing. A Brahmin girl can’t live with the Madigas, so I couldn’t go live in his house. He obviously couldn’t live on Pray Street with the Brahmins. They decided we’ll live with the Shudras on Labor Street.”

And I sit with the Shudras on the back benches, Reva thought.

“It wasn’t kindness,” Amma continued. “What use is a corpse? A man who’s alive, they can hunt him a little every day until he flees. And an abandoned woman? They’ll make her regret her decision for as long as she breathes.”

Soon after Reva’s birth, Nana left for Chittoor to spend the summer working on a date farm. Just as he did every summer. That year, however, he didn’t return to the beginning of September. Reva was born two years after her parents got married. So Nana endured their torture for two years but left once he saw her. Why? Over the years, she’d return to the question, she’d grasp at answers that never felt satisfactory but she wouldn’t stop trying, not even after she realized the impossibility of knowing the heart of another.

Reva got up and went to Amma’s bed. She stood at the edge until Amma made room for her. She lay down, wrapped a clumsy hand around Amma’s shoulder, and lowered her head until she felt Amma’s chin against her scalp. She closed her eyes and fell asleep.

***

Kaveri bathes and dresses Prashu. Reva takes him to school. They walk through the temple district, past storefronts stacked with baskets full of orange marigolds.

“When I was eight,” Reva says, “I became friends with a woman called Blade.”

“Why ‘Blade’?” Prashu asks.

Reva replies, “She sells coconuts and opens them with a sickle that’s as sharp as her tongue.”

Prashu asks, “Did she teach you kicking skills?”

Reva laughs and nods. “I liked to stroke her hair.”

“What was it like?”

“White as clouds, just as fluffy.”

Prashu brings her to the local ruins. They have their classes in an abandoned prison, Reva learns. Jailbirds once scratched their names on the wall. His first-grade Telugu teacher incorporated those names into her lesson on the alphabet. ‘Ra’ for ‘Raju’. ‘Ki’ for ‘Kiran’.

At the school’s threshold, Reva encounters a smell she’d abandoned at eight. Chalk.

“What do they teach you?” she asks.

Prashu rattles off a list. Anamaya’s poems. The geography of Andhra. The violent history of the state’s formation.

“Will you teach me?” Reva asks.

“What?” Prashu asks. “History?”

“Anything.”

“Didn’t you go to school?”

“Not for long.”

The school bell rings. Prashu runs in. He sits up front with the other Brahmin boys. Shudra boys on the back benches. The Madiga boys on the floor.

Instead of returning home, Reva crosses Sindhu’s Swing and enters the Madiga settlement. The narrow road is flanked by tightly-packed huts. Women squat before their homes and speak to each other as they chop fish or onions on newspapers spread open on the road.

Reva’s presence brings their conversations to a standstill. A woman, further up the street, hastens indoors. A moment later, a man with a cloud-gray beard steps out and sunburned skin walks towards Reva. He stands at some distance and speaks to her.

“If your people see you here, they’ll have our heads,” he says.

“I’m one of you,” she confesses.

“Only half,” he says. “If you were one of us, you’d know the difference.”

“My father,” she begins.

“He was foolish to marry your mother,” he says.

Reva looks at his face searchingly. As if to understand how, with nothing more than a glimpse, he arrived at her precise genealogy.

“Please,” he entreats. “You must go.”

He joins his hands and bows his head. The gesture stings her. She recognizes his voice.

“It was you who sang last night,” she says.

He lifts his head and smiles, his art briefly restoring the pride that was taken from him.

“Your skin gives you away,” says the woman who fetched him. Her expression, Reva notices, has softened. There is a glint in her eyes. “Adivi-tata is our best singer no doubt but he’s no clairvoyant—even though he likes to fancy himself as one.”

Reva shares with the strangers an honest laughter.

Why did Nana leave? Once more, the question comes for her as she walks back home. He didn’t want his child to see him as helpless, Reva thinks. Getting thrashed by village men, unable to do a thing about it. The speculation doesn’t quench her thirst. But for now it stills the tic.

Reva sits in the backyard, the sun warm against her feet, her face shaded by the shadow the house casts. Kaveri returns home with Prashu. He calls for Reva. He runs into the backyard, looking for her, Kaveri hot on his heels, asking him to change out of his uniform first.

“Tell me more Blade stories,” he explodes.

When Reva looks up, his expression changes. He sits next to her and reaches to wipe her cheeks.

“No,” Reva says. “I want to feel them on my face.”

He strokes her hair instead. “Black as cow-dung, just as soft,” he observes.

“Prashu!” Kaveri scolds.

Reva bursts out laughing. Kaveri joins her. Their father-in-law is napping and doesn’t cut their laughter short.

***

Piśāci. Even her classmates started calling her that.

“Piśāci, with a skin dark as buffalo’s,” they sang in chorus when she entered the classroom one day. Reva knew it was the idea of Lady Sivagami, the revered leader of the girls who came from wealth and belonged to the top two rungs of the caste ladder.

During recess, Reva walked up to Lady Sivagami who sat surrounded by her girls. They ate from gaudy lunchboxes without slurping.

Reva asked, “Did you come up with the song?”

Lady Sivagami’s devotees looked at her expectantly. She had to rise to the occasion. She literally did. She stood up and pressed her fists to her hips.

“Song is a bit rich for you,” Lady Sivagami said

Reva smiled ruefully. “Wish I was one wise modda like you.”

Lady Sivagami looked pleased and perplexed. Pleased by the compliment of ‘wise’, perplexed by the supposed-compliment of ‘modda’. The word slipped from Reva’s tongue easy as spit. She knew that Lady Sivagami’s sanitized upper caste upbringing made room only for caste hatred, not swear words.

“Say ‘wise modda’ before Sarita Madam,” Reva suggested. “She’ll finally praise you.”

“Why are you helping me?” Lady Sivagami asked.

“I want to be your friend,” Reva said, looking doe-eyed and sincere.

“We’ll see about that,” Lady Sivagami said.

The next day, Sarita Madam began History with a question. Why did King Asoka turn to Buddhism? Lady Sivagami stood up and said, “Madam, Asoka-garu became Buddhist because he was a wise modda.”

The Shudra and Dalit girls gasped. Sarita Madam hissed, “What have you done with your shame?”

The whole class burst out laughing. To Reva, it was music richer than birdsong.

During recess, Lady Sivagami pressed her hands to her stomach, claimed she had a belly ache and left without turning to look at her girls. They’d let her down with their laughter. But the next day they redeemed themselves by ratting Reva out to Sarita Madam. Reva was sent home. She was to return the following day with a written apology addressed to Lady Sivagami.

Amma came right back with her to school and demanded, “Where’s Reva’s apology?”

“For what?” Sarita Madam asked.

“For calling my girl a piśāci,” Amma said. “And a buffalo.”

Sarita Madam listened to Amma, as if she was interested, then repeated that Reva must apologize for providing sinful words to impressionable minds.

“She won’t say sorry,” Amma said.

“Then she’s not welcome here,” Sarita Madam said, a grin tensing the edges of her lips.

First the parents show up in the principal’s office with their sob stories, then the girls squat before her and demand History and Maths. All without a single paisa to their name. What would her salary be if they paid their fees? Equal opportunity my foot. A bunch of goats fattened on free meals is what they are.

Reva ascribed these meanings to that thinly-concealed grin. She spat on her teacher’s hand. Sarita Madam watched agape as the gob of spit dripped down her thumb and landed with a splatter on her sandal. Reva was impressed with her spit’s perfect trajectory.

She kicked stray stones and whistled a Vijayashanti film tune as she walked back home with Amma. Bye Lady Sivagami. Bye Sarita Madam. Bye back bench.

***

Reva’s husband returns from his tea estate in June. It’s past midnight. None of the usual ceremony precedes the Bridal Night. He simply slips under the covers. Presses his body to hers. Cold. Smelling of city fumes. As though they’re an old couple, their intimacy routine.

Daylight reveals her to him at last and him to her. Dejection fills his chubby face.

“Give me a boy who looks like his father,” he says with a boyish grin. It leaves his face and a blush takes its place when she meets his round eyes and holds his gaze.

All day long, father and son slump in recliners set one next to the other in the drawing hall. Between naps they demand glasses of filter coffee and buttermilk.

One day, as Reva oils her father-in-law’s feet, she says, “Try walking every day for a few minutes. It will do you good.”

“Take two sips of that oil,” her father-in-law says, “And never tell me what to do.”

The next morning, Reva makes another cross under the bed with a chalk.

“What you doing down there?” Kaveri asks from the door.

“Come here,” Reva says.

Kaveri crouches and crawls next to Reva.

Reva counts the crosses. “He spoke his seventh sentence to me last night,” she says.

“Your man?” Kaveri asks.

“Said my mouth tasted bitter,” Reva says.

That evening, Reva watches Kaveri add a pinch of cayenne powder to the oil she heats. Reva brings the oil to her father-in-law and massages his feet.

Well after her man is done with his business and sleeps his animal sleep, her father-in-law’s groans begin. Reva doesn’t stir. Neither do Kaveri or Prashu.

The next day Reva fetches a doctor who examines her father-in-law’s feet that, by then, have turned to the color of beets. When the doctor gets up to leave, Kaveri picks up his bag and walks him out. When she comes back in, she waves a pill strip and tells her father-in-law, “Doctor-garu says a tablet every night after dinner, a five-minute walk after lunch.”

He receives this instruction with a look of resignation. It erases the bitter from Reva’s tongue.

***

As Reva walked back home from the marketplace, her old schoolbag heavy with produce, the temple priest stood in her way. He smelled of camphor.

With his gaze fixed on Reva’s chest, he said, “You’re ready.”

His acolyte hesitantly said, “Sir, she’s a child.”

Reva was thirteen. The priest, old enough to be her grandfather, scratched his stubble-chin and retorted, “Didn’t your school teach you grammar? She was a child.”

She came home and told Amma what the priest said. You’re ready. Amma’s return that night wasn’t punctuated by the familiar rustle of money tucked under the pillow.

The priest ignored Reva thereafter.

Three years later, the same priest came home with a marriage proposal for Reva: an older man, but wealthy by way of his tea business; he sought a young Brahmin bride.

Amma’s brown eyes lit up. She pressed the edge of her sari to her chin.

“We won’t mention the father’s caste,” he said.

That night, Amma came home and lay down on the floor behind Reva. She smelled of camphor.

She said, “After your wedding, you’ll cross Yamuna’s Arrow to reach your new home, and once you do, you mustn’t look back.”

Reva heard Amma sniffle. She turned and lowered her head until her scalp grazed Amma’s chin. Amma gripped the nape of Reva’s neck and said, “If they know who your father is, they’ll send you back. Our family will not give the men of this village another sacrificial goat. You understand?”

“Yes,” Reva said, because she understood Amma loved her unconditionally.

***

Reva’s child is born on March 31st. Reva’s forehead is damp and hot; her eyelids burn and water; she’s out of breath but the breath she draws leaves her breathless. She turns to the body of her newborn for comfort. The girl is asleep. Her forearm is a lawn of human hair. Her dark skin is shriveled and she’s toothless. As though she’s born an old hag. When she wakes up, she blinks her overlarge eyes at Reva. They’ll call my girl rakshâsï, Reva thinks. A demon.

An astrologer comes home to draw the newborn’s birthchart. Her husband and father-in-law are napping. Reva meets him.

“Date and time of birth,” he demands.

“Tell my husband our girl will bring him good fortune,” she says.

“What’s in it for me?” he asks.

She answers his question. He scratches his neck and grins.

Three days later, the astrologer returns with the natal chart. He sits next to her husband. Reva stands behind them.

“Your girl will bring you good fortune,” the astrologer says. “Fertile soil and tea sales.”

After dinner that night, Kaveri washes the dishes, Reva dries and puts them away.

“I have a game in mind,” Reva says. “Want to play?”

The night of the new moon falls four days after her husband’s leaves for his tea estate. Once her father-in-law retires to his room, Reva picks her child up from the cradle. The girl doesn’t stir from her sleep. Reva conceal her with the edge of her sari and leaves the house.

The astrologer, waiting for her under a banyan across from the house, follows her into night.

Reva crosses Sindhu’s Swing. Her gait is swift. The astrologer cannot catch up to her. He says something but distance and his breathlessness reduce his words to a babble. Reva enters the cemetery. He joins her several minutes later.

“Lanja,” he cusses, huffing, panting, striking a match, finding her face in its light. “Is this where you bring a man like me to?” She unveils her child. His face darkens before the match burns out. “Why did you bring your baby?”

Reva sees a light bobbing over Sindhu’s Swing.

“Put her down,” he says.

She hears him fumble with the folds of her dhoti.

“No,” she says.

In the dark, he shuffles towards her. His hand finds her head. He grabs her hair.

“Put her down or I swear I’ll crack her skull before I get to business.”

With her free hand Reva hitches up the folds of her sari and swings her knee into his crotch. He howls, let’s go of her, doubles over. He doesn’t see the light that’s now bobbing over Sindhu’s Swing. With the folds of her sari still in her fist, Reva raises her leg and kicks. Her foot meets his thigh. He falls on his back and goes skidding between the urns.

“What’s going on?” Kaveri says, holding her lantern over him.

He’s startled by the presence he didn’t anticipate. He sits up. Reva screams. Kaveri joins her. The baby wakes up and wails.

Quivering orange blobs speckle the surrounding darkness. Seven men come running into the cemetery, holding torches.

Reva hears their breaths. She feels the heat of the torches that they hold at a tilt. Her body and that of her child—who, in that commotion, has gone quiet—are washed in an orange glow. The night fills with the stench of kerosene. Kaveri comes and stands next to Reva. A man steps forward and lowers his torch. It’s Adivi-tata.

“This is my sister-in-law,” Reva says to him, gripping Kaveri’s forearm. “She comes here every new moon night to pay her respects to her husband.” She cups the head of her child. “I brought my newborn to be blessed by her ancestor.”

“That’s when he ambushed us,” Kaveri says, pointing at the astrologer.

“Look at this superior Brahmin, brothers,” sneers Adivi-tata.

The men pick the astrologer off the ground and throw him back down. His cries are barely audible over the cacophony of their name-calling and howls. As they kick him, rain him with blows, Reva sees not him but the violence he’s subjected to. It becomes the violence that should’ve injured every man who violated her father’s body, who followed her mother into the night. After a moment, Reva steps forward.

“Stop,” she says. Then, louder, “Stop. Please.”

Adivi-tata, who hears her, pushes one man after another away from the astrologer.

“If he dies, they’ll have your heads,” Reva says.

“You’ll do as I say?” she asks the astrologer. “Answer me!”

He sits up laboriously, presses a palm to the gash on his head, and nods, his eyes wild with fear. Reva looks at Adivi-tata. He pats the shoulders of his men. They file slowly past her and out of the cemetery, their bodies shivering from the rage expressed but not spent; the body they’d beaten, Reva feels, ceased to be a specific; it teemed with the bodies of all the men who’d ruined them in the name of caste.

Reva says to Adivi-tata, as he’s leaving, “No one must know.”

He looks at the astrologer. “Not unless you want them to.”

Reva bends and touches his feet. She stands up and catches a glint in his. After a moment’s hesitation, he brings a hand to the scalp of her child and says a blessing.

“Thrive.” Brief, but pulsing with the energy of Sri Sri’s protest songs.

After his departure, Reva speaks in the dark. She demands from the astrologer predictions that will secure her child’s future: name her Ganga; educate her or you’ll incur the wrath of goddess Lakshmi; don’t get her married before she’s eighteen or her father will die.

“This is sinful,” he mumbles.

“Sin is a bit rich coming from you,” Kaveri says.

They cross Sindhu’s Swing. The torches, Reva turns and sees, are still burning. Her child, asleep against her shoulder, stirs but doesn’t wake up. Nana left, Reva thinks, when he knew Amma was no longer alone—she had their daughter’s company.

“Why Ganga?” Kaveri asks.

Reva replies, “Amma’s name.”

“You’re starting to sound like a proper Rayalaseema girl when you’re angry,” Kaveri says.

“When I’m not?”

“You’re a boring old coastal Andhra girl.”

Kaveri links her arm with Reva’s. Reva kisses her on the head.

As they walk home, Reva understands the origins of Sarita Madam’s barely-concealed grin. She was pleased because she got to turn away Amma, the woman who could’ve been her neighbor on Pray Street but who, with one foolish choice, was left with neither status nor husband.

Amma gave her daughter what she didn’t have: the security accorded to a married woman. My child, Reva thinks, must have what I don’t: a future where she earns her keep on a land separated from Reva’s by too many bridges to count on both hands.

Back home, Reva lies down and closes her eyes. As she’s drifting into sleep, she sees Amma’s oval face. If she stretches her hand, she’s convinced, she can run her thumb down her Amma’s thick eyebrows.

Ganga wakes up at four and goes back to sleep after drinking some milk. Prashu wakes Reva up a few hours later. It’s a Sunday so he’s not in his uniform. Reva smells chalk powder. She sits up.

Prashu sits next to her and offers her a slate and a box of chalk-sticks.

He asks, “Where do we begin? History, Arithmetic, Geography, Telugu grammar?”

Reva answers without hesitating. She knows what she wants.

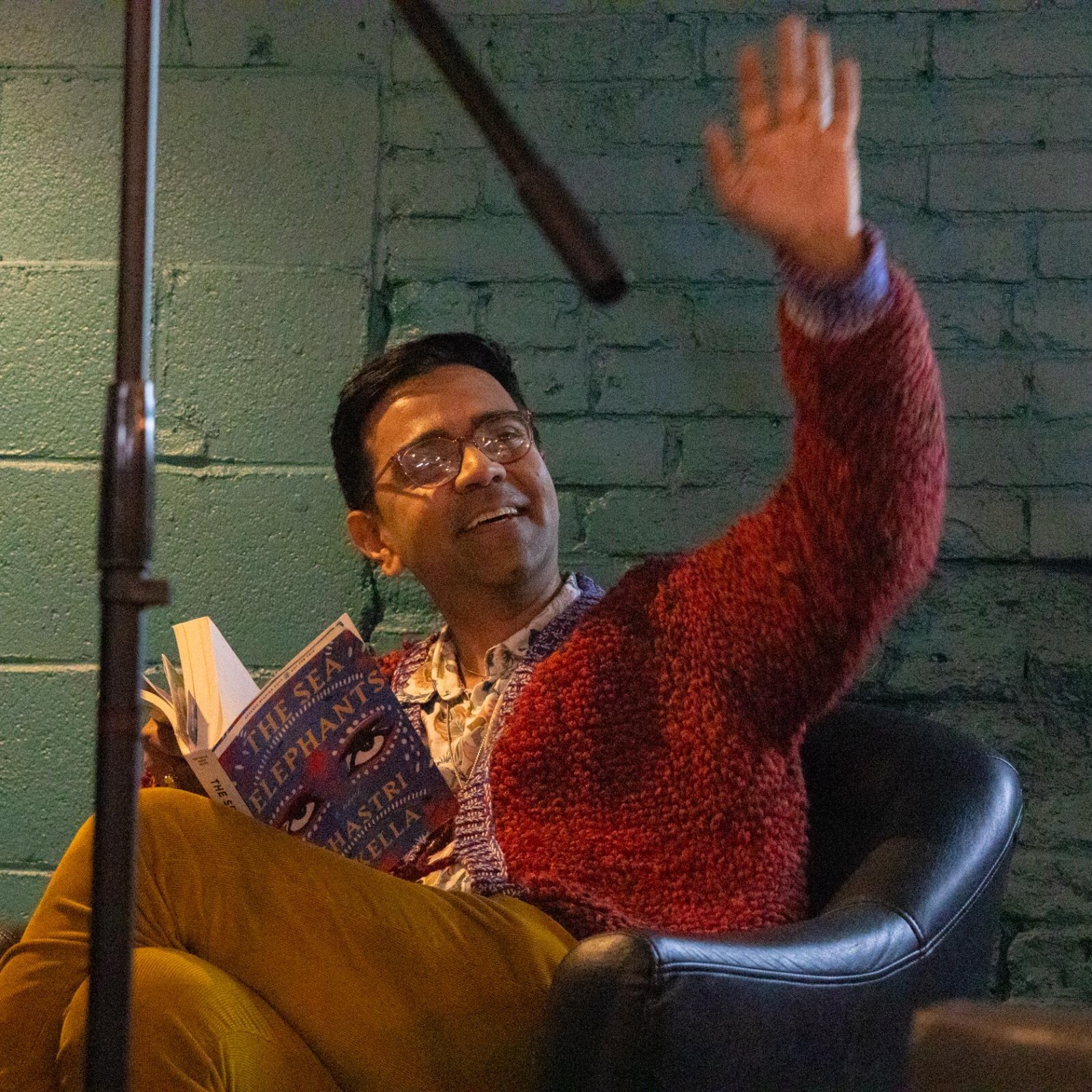

Shastri Akella (he/they) is a queer migrant of color who is neurodivergent and comes from a working class background. Their debut novel, The Sea Elephants, was published in 2023 by Flatiron Books (USA) and Penguin (India). It is a queer bildungsroman set in 90s India. They won the 2024 BLR Goldenberg Prize for Fiction. Their story was selected for the 2024 Best American Short Stories. You can find their writing in Guernica, Fairy Tale Review, LitHub, The Rumpus, World Literature Review, and elsewhere. Originally from Vizag, they now live in East Lansing and teach creative writing at Michigan State University.