Night Moves

Ross Showalter

It takes me three weeks after the break-up before I realize something’s wrong. I wake up at crushing times in the night, always because of my body. Sometimes it’s my underwear wet and sticky or my pillow wet with tears, other times it’s my hands: fingers fumbling, fists forming. Sometimes I wake up and my arms are crossed upon my chest. Those nights, I wonder if I want to die, but I also know crossed arms like that means love in sign language. I don’t allow myself to go past that.

The night after Thanksgiving is when I don’t roll over and go back to sleep. My underwear is sticky again, my fingers curling in the pillow next to me.

I sit up, wondering if the city lights dappling my walls, the rain tapping against every window is part of another dream—my body doesn’t feel like mine anymore and I wonder if my body can’t give itself back to me, if I need more than time. It’s been a month since the break-up now and I’ve started to dread sleep, the miserable yawn ending with anguished wet.

The rain knocks against the window, beyond is the glow of city lights, further than that is pitch night. My fingers tremble when I open my laptop but I refuse to surrender. It’s been a month.

I’m making an appointment with the doctor, I write, because I’ve been having trouble sleeping.

I wanted him before we even met.

I saw him at a class, an informal sign language class in the back of a gay bar. He was shy, hanging outside the circle of students, watching the teacher flirt with the handsome ones in between teaching signs. He was a golden boy, with his pale skin and blond curls. I saw his wet mouth and glistening eyes. I saw the breadth of his shoulders, how he filled out his t-shirt, and I stiffened, and I wanted.

I had been hesitant about coming to this class. I avoided bars. I was thirty-two and had decided this new decade was going to be different than my twenties, different than the nights full of dark corners and anonymous crotches. I could only remember two weeks’ worth of hands and mouths before getting confused.

Still, the receptionist at my work had praised the class after I’d caught him fingerspelling the alphabet during one lunch break. It was every Wednesday night. There was an ASL interpreter who spoke the lessons into English, for those who didn’t know any sign language. And it was so easy to learn, to use your body. The receptionist had winked at me, eyes gleaming above his dark beard, talking about the boys, the boys—as if we were grey-haired men ready to hunt and devour a red-hooded traveler.

Something about what the receptionist was doing, how precise the movements looked, made me ask if I could tag along. I told myself going in if anything was going to happen, it would happen for more than a night. Seeing the boy in the bar, all shining innocence, I knew I could focus on sign language. Hearing aids wrapped around his ears, and I wanted every barrier between us gone.

I worked my way over to his side, leaving the receptionist and my drink behind. The boy caught me staring sideways at him and flushed red. But he was smiling too. We watched the teacher sign about gender terms; he’d chosen that topic because it was the end of July, after all, and he wanted to know how much we remembered of June. The interpreter spoke slow and steady over the music from the jukebox, barely keeping us afloat above the pound of bass.

I glanced at the boy again, and he was tapping away on his phone. But he touched my arm and there was his phone, a question written on it. A question for me.

What’s your name?

I gave it, tapping it out on his phone.

Are you visiting?

I wasn’t. I was a psychiatrist that worked and lived in the area. His bottom lip caught under his teeth upon reading and I was flying over the desert blanketing my stomach.

How close are you? was his next question.

We ended up in the bar’s bathroom first. I pressed my body against his, sandwiching him against the stall door. His mouth was soft and pliable, his neck thick, ropey muscle under soft unmarked skin. He smelled like cinnamon, and I wanted more. I grabbed his ass and he exhaled sounds of reverence, like we were in church and taking communion. After that, I didn’t know where he ended and I began.

You’re having trouble sleeping, is that right?

I nod. The nurse smiles, looking down and making a note on her clipboard. She’s like the rest of the room, all soft corners, soft glow. I couldn’t fall asleep after making the appointment, my spine stiff at the idea of entering the doctor’s office as a patient. I hadn’t made any special appointments for years. I was careful to not get sick.

What are the sleep disturbances like?

I feel my face grow hot. I have to admit it, Well, a lot of sex dreams.

The nurse is neutral, A lot of sex dreams. Okay.

I almost tell her about my hands and arms, forming signs I barely know and use. But the doctor doesn’t need to know more than is necessary. I wonder if my hands will still once my body returns, and I don’t feel the tug of anticipation I thought I would.

My doctor is typically brusque. How’s work been treating you? he asks me.

I shrug, It’s work. I see clients. I counsel them.

You don’t have a history of mental illness, do you? Or any mental problems in your family? he asks. No, sir, I respond. No, sir.

So, what’s bothering you?

I can’t take my eyes off my hands, but I tell the doctor enough, taking care to avoid gender pronouns. When I finish explaining and my hands remain steady, I look up at him. His brow is furrowed, his mouth tight with professional sympathy. It startles me; it’s a look I’ve worn myself.

You been in any kind of intense relationship like this before? he asks.

I shake my head, Not like this.

He gives me a prescription for temazepam, a sleeping pill. Non-habit-forming, but I’m only giving you enough for a couple weeks anyway, he tells me. There’s also a psychiatrist in Fremont, very good at her job. You should go see her, see if it helps you any.

He gives me the name and the address of her office: it’s a seventeen-minute drive from my apartment. I imagine being back on the other side: my back flat against a chaise lounge chair, my eyes fixed not on the ceiling but some memory as the pen scratches away on that legal yellow notepad. I wonder if my body will betray me before I even open my mouth.

I get my prescription and enter my apartment with it. They’re white pills, the little orange jar half-full of them. I set them on my nightstand. My bed is calling me back; it’s not even noon yet. Sleep laps at my consciousness, asking me to just take a pill and dive.

I resurface hours later. The corners in my apartment are more pronounced, the colors brighter and distinct. My underwear is dry and it feels strange shucking off fabric that isn’t stained sticky with dreams. In the mirror, I notice the bruises under my eyes becoming lighter, closer to grey, the grey of dust; and I hope for the shower to take care of the rest.

(Take back your hands. Hold out your dominant hand, palm up. Your other hand curls into a fist, except for your pointer and your middle finger. Rest those two fingers on your dominant palm. This is the sign for “lie”, as in lying down. Imagine those fingers as your legs, your body. Consider how weak those fingers feel.)

After that bar meeting, after that night when we barely slept until we had to, he took several days to answer my requests for another date. His texts were short and terse. I could read the nerves between each word and I asked him what was wrong the next time we met, this time over coffee.

He flushed, looking down at his mocha. The barista, another golden blond, had made him a milky heart on the surface; and I wondered briefly if they were romantic. The boy had wanted to come to this café and it felt otherworldly, the sunlight coming in pale through the windows and the workers barely making a sound. Apart from two people hunched over computers, we were the only customers. He had said he wanted a quiet place, and I had gone along.

I don’t really date people like you, he said. His voice was soft, high, sweet like a child’s, and he sounded like he had a cold even though I knew he didn’t, the edges of his words cloudy and unsure. It’d been a voice curated through years of speech therapy, he’d told me in bed. I found it adorable.

What, you mean older guys? I asked. He was nine years younger than me and had graduated with his Bachelor’s in Theater from a school in D.C. only weeks ago.

His color deepened. I mean, people who can hear, he said. You’re the first hearing guy I’ve seen more than once.

What I gave him in response was nothing but promises. I would learn sign language for him. I would try to be a decent person around him. I would be a guide for him—

No, but I don’t want a guide, I don’t need a guide, he said. I’m not an invalid. I just can’t hear. He saw something in my face and his expression softened. It would be great if you and I could find common ground in terms of communication, he said. You do some of my language and I do some of yours.

I encouraged him to drink up the heart in the cup then. I had some learning to do. We went home to my apartment and I couldn’t wait for us to get to the bedroom. We fucked on the living room floor, his back writhing and arching, all fleshy hills and plateaus until he let out a guttural shudder and quaked under my palms. That had been the first of my lessons in communicating with him: my hands learning the landscape of him before he took over, moved my fingers until I got each letter of the alphabet right.

(Crush—the fingers of your dominant hand gather together into a fist. Go knuckles first into your other hand, into open palm. Make sure you give the sign the gravity it deserves, the gravity that makes you both sail into the sky and slam into the ground, a devastation. It’s impossible to fly. Everything that rises must fall.)

My last patient on Monday is one I’ve been seeing for years: a chronic smoker with twenty years of daddy issues. She perches on the chair like a bird might on a tree branch. I start off with questions about her younger sister but she’s distant, staring below my chin into nothingness. Her words flutter and trail down to silence several questions in.

I prod her, What about your sister? What was it you were saying about her?

She looks in my face then, I didn’t know you knew sign language.

I’m sorry?

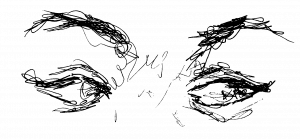

She points. I look down at my hands, and they’re moving of their own accord, forming the letter S and then I, and then I stop myself, stop my hands from doing any more. The pen I was writing notes with is on the floor. I wet my lips, my hands are fists, and I try to tamp the mounting panic as I bleat something about taking a sign language class, an informal one long ago. I feel revulsion as a wave of sweat. This isn’t me when I’m working. My hands don’t carry my own emotions into my office—my hands don’t carry anything from me at all.

Well, you must like sign language, my client says. A smile is playing around her lips. I’ve lost control, and she sees it.

I press my palms together, intertwining my fingers. Please tell me more about your sister, I say.

As the patient talks, I feel the pound of blood underneath my palms, the same kind of throb I would feel all over after sex. Weightlessness swims in my stomach, as if desire is ready to jerk me around like a puppet. Then I get an erection, and I have to cross my legs and park clasped hands right above my pelvis in a show of chastity, of control. The golden boy tugs at me, asking me to come back to the snarl of our relationship, a forest where there’s no clear path.

I persist, leaning forward and listening to the client. I don’t take any more notes. The session can’t end soon enough, with her wiggling her fingers good-bye as she walks out.

Good luck with your sign language, she calls over her shoulder. Bitch.

The receptionist glances at me and I retreat back into my office, adjusting myself. I’m not out of the woods. After the first ASL class together, we hadn’t gone out together again. I wanted to maintain some professionalism. I was the youngest psychiatrist in my building and I needed to be taken seriously. I wonder if the receptionist’s glance is tinged with amusement, lips twitching under his beard. He knocks on the door minutes later, a two-time rap. I keep my body out of view as I answer.

I heard the patient. I didn’t know you were still interested in sign language, he says, eyes bright. I shrug, mumbling something about how muscle memory could be hard to break.

No, but you didn’t stay with him for very long, did you? the receptionist asks. That’s what he told me—no more than three months.

My hands feel numb, the weightlessness now in my head like I’ve gulped too much oxygen. It’s all I can do to hold myself upright. You’ve seen him? I ask.

He came to the bar, the receptionist replies. I was there.

Something about his eyes, the way they catch the light, make me want to ask for more, prod for more. But he steps away and I’m still holding on, still lost in the deep dark forest. He steps away and I can’t reach out and grab him. I can’t use my hands on him. I can only close the door on his profile, wanting to swipe out the hot glittering in his eyes.

I go home and masturbate in the bathroom, wishing I was with him, wishing it was his hand. My orgasm is an electric shock, scoring deep in my thighs and gut. I take one sleeping pill, but that’s not enough to be numb. The pain won’t go away with one. I tip my hand until more pills scatter across my palm. Three, four, five—they all go in my mouth. I want to be numb, numb and away from the receptionist, away from the golden boy, away from my hands. I drown my orgasm with a gulp of water, surfing the pills through my body.

We didn’t go back to the class where we’d met. He didn’t want to go, saying that the teacher was more interested in sex than teaching. The teacher would try to seduce me. The receptionist asked me every Wednesday regardless, You and your boy coming tonight?

No, I replied every time. It’s going to be a low-key night for us tonight.

The golden boy started teaching me sign language in the bedroom. He taught me how to introduce myself, spell out my name and his. He taught me signs that made me blush as I did them; he said these were necessary signs, slyness curling around his words like smoke.

After a couple weeks, the clouds of apprehension started to fall from his eyes and he eagerly approached me with new signs all the time. I loved it, loved being able to expand my vocabulary so rapidly. The sunny excitement from him put me under a spell. I was his, and he could teach me anything he wanted, whether it be his body or my hands.

Then I started feeling like I was treading water. I started mixing up handshapes, like the letters D and F. I confused the signs for coffee and make out, and he kissed me deeply a couple mornings before seeing the dripping coffeemaker and catching on. It was all about hand placement.

It was also all too much at once, my hands trying for something and grasping something else. I needed to take it slow, I told him one August morning, the last morning he drank from my mouth. The disappointment from him was palatable, a bitterness under the tongue that was hard to rinse.

I really do want to communicate with you, he said. It’s hard to lip-read.

I made concessions with him. I shaved off my beard, a decision that left me vulnerable in ways that couldn’t be salved by him stroking my jaw. I watched videos of signers at work when a session was canceled, when I had time between clients. I borrowed textbooks and flipped through them until descriptions of signs seeded themselves in my everyday thoughts, bursting and blooming behind my eyes.

After work, a couple days a week, I would meet him at the Starbucks across the street. I’d find him at a table, hunched over a sprawl of papers. He always had a mountain of applications, a mountain of scripts. I never saw the tabletop when he was working on those, just white sheet after sheet, a snowstorm of business and opportunity.

Sometimes, he wouldn’t be hunched over them: his eyes would be heavy-lidded with defeat then, and when I sat down, he’d tell me of rude casting directors and the awkward encounters with potential bosses who didn’t know how to work with a deaf person. He could get by with working in a coffee shop, the same job he’d snagged when he’d first moved here, but he didn’t want to.

It’s always the same, he said every time. They only want the people who’ve been on Broadway, the ones who’ve gotten lucky a thousand times over straight out of university. There would be abject misery in his voice, the kind I could fall into. The first time I’d encountered that pit of emotion, I’d reached across the table and covered his hands with mine. I’m so proud of you, I said, signing proud: my thumb racing up my chest. Anything to stop that deep descent.

He had glared at me, his eyes heavy no longer. For what? he asked, his voice flinty and brittle. He sounded decades older and I almost drew back then, shocked at his bitterness. He seemed harsh and cruel in that moment, no one I wanted to know. After, I had let myself only be silently present, even when he was slumped with dejection. After some minutes, we would go home, and by the time he peeled off his underwear in my bedroom, he was always smiling and tender, he had left his defeat behind.

The boy had me meet his deaf friends when we made a month together, introductions that pinned me under sharp, distrusting gazes. Deaf people were slow to warm up, the boy said; they just needed time before they let me in. I felt like a visitor, always knocking on the gates.

After those uneasy introductions, we started meeting his deaf friends every Friday night, always deep in some bar, always under light that barely illuminated. I would order something light or non-alcoholic, needing to be sharp in unfamiliar territory. He wouldn’t. He and his friends tossed back whiskey or vodka, giggling, hands knifing throughout the air and drawing blood in ways the golden boy would point out—that sign meaning legitimate, this sign meaning bullshit. I would pay for second and third rounds, trying to charm them. Those rounds only served to ruin them, level them into grunting, swaying, impassable mountains.

The boy tried to kiss me whenever we got home, grappling for my crotch. I learned how to handle him, navigating around his curling, pushing fingers until I got him into our bed. I couldn’t smell his cinnamon smell those nights, it’d drowned into alcohol with him.

On those nights, barely conscious, he seemed to be grasping not for me but for something beyond me. When I joined him in bed, he showed me his back, a familiar sword and shield. Those nights, no matter how much he drank or what I did, I could never disarm him.

(Contemplate your past relationships as you sign the word “relationship”: how your thumb and index finger come together, interlocking with the other thumb and index finger, with the other fingers spread out, left out. There’s always a back and forth, but hands can’t show how violent that tug-of-war can be.)

My underwear is wet with piss, my hands trembling. The sheets and covers are kicked to the floor. The bedroom feels like another dream, me sluicing through the morning light as if it’s a flood of water. The corners of the room remind me of scar tissue, the walls fragile as eggshell. I fall on my ass halfway to the toilet and don’t feel anything. Concern flickers as a dying flame. The pill bottle sits on the counter and I notice it is emptier than last night, much emptier.

I shake my head, trying to break through into the morning. I need to wake up but I took too many pills—several nights’ worth. My legs shake when I get up from the toilet and even the gurgle of the flush sounds like it’s in the other room.

I can’t go to work today; I need to call the receptionist, tell him I’m sick. His glittering gaze lunges back into my mind, his smile a thousand times crueler. I think of my boy’s back, cold and unresponsive, and I start to like my emotions being as dull as they are, as if my heart is outside of me, barely needed, barely used.

(Run your hand along your chin, fingers leading the way. This is the other sign for “lie”—not telling the truth. Be sure to catch the dribbles of what’s unsaid, leaking like blood from the corner of your mouth.)

There would be days and nights we wouldn’t spend together, especially after his nights of drinking. He would leave after a cup of coffee, and he never asked me to go home with him. He never brought over his stuff to my apartment, which conjured in me a strange sense of relief.

Those days and nights without him, I would be at work or in bed, either asleep or wanting to sleep. Sometimes I pulled up a textbook or a video and tried to learn some new signs. He always asked me if I wanted to learn something new, and I hadn’t realized how much of a dance this relationship would be until I was in it.

I brought this up multiple times with him, how I didn’t want to burn out; he needed to be patient with me. He thought this unfair.

I can’t just lip read like I read a book. I can’t just go along on your terms, he said when I brought this up. My terms were bad and communication was bad, never mind my naked jaw and hovering fingers. He told me it was a guessing game reading my lips, he struggled with forcing out soft consonants. He did more work than I did every day.

The sex between us became a filter. Only when I jackhammered into him and saw his eyes roll back into his head could I talk with him. After, he was like when I first met him, eyes soft and wet with pleasure. Sometimes I wanted to shove him down to the floor, hold his back against the carpet until he got burns from what I did to him.

As the leaves blanketed the ground more and more, I found myself protesting less but my fingers sung with a dull ache. I gripped at his hips and his ass less and less. But we needed each other because we both had something to prove. His deaf friends didn’t soften their suspicious stares or lower their defenses. The boy told me, eyes ablaze with defiance, that they bet money we wouldn’t make a year. Hearing people always backed out, the friends said, the golden boy had poor judgment. I remembered my own parents reacting with the same kind of scorn when I had told them I loved men.

Gay people don’t love each other, my father had said, they just lust. I wanted to bring the golden boy to Wyoming for Christmas and prove my father wrong.

So, I persevered, always signing yes when he invited me out to meet with his friends at the bar. Often, I would slump at the table, watching a gesturing show that I had little access to, the boy’s foggy voice whispering less and less in my ear. I couldn’t understand the hoots of laughter, the oversized gasps. Sometimes I decided to not care.

The ground gave way below us one of those nights. He’d gone on a particularly nasty streak of drinking, polishing off several Halloween-themed cocktails when Halloween was days away. He put his mouth on my crotch in my apartment doorway, mumbling about how he was Dracula and I was Lucy. I was his willing, sweet victim.

I manhandled him into my bed with more force than ever before. His teeth gleamed in the moonlight. He didn’t settle down and close his eyes but watched me as I left him alone.

I drank two glasses of water before I heard the rustle of sheets and the creaking of bedsprings. A third glass of water and he was snoring on the last mouthfuls I swallowed, the crackle of his sleep noises making me feel like his nails were scraping inside my stomach.

I didn’t want to get in bed with him. I put the cup in the sink and left my own apartment.

I went back to the bar where we’d met and it wasn’t to reminisce. The bar was full of the usual Saturday crowd and I carefully scanned the clustering and drifting bodies to make sure no one’s hands moved past standard gesticulation. I got a cider, sweeping around the bar again. My gaze locked with another’s, a younger guy but not as young as the boy. He wasn’t golden either. He was hovering around a corner, on the edge of the shadows, and I recognized the hunger in his eyes. I’d been there before.

I brought myself and my drink over to him. I flirted and touched and so did he. His voice wasn’t cloudy, it was a window of sunlight. He could hear, but his eyes still drifted down to my lips. They drifted there and stayed when I slid a hand up his thigh. The denim underneath my palm felt like a promise. In the bathroom, he wasn’t shy about sticking his tongue in my mouth, he wasn’t shy about inviting me back to his place. I went home with him.

I left the one-night stand when he fell off our peak and deep down into sleep. It was raining outside, big fat drops splashing down on my face, my shirt, my hands; I’d forgotten a raincoat. Something in me didn’t care about being wet, the same part of me that didn’t want to get in my own bed. Defeat was stirring awake, squeezing around the layers of muscle that made up my heart.

I stir. I stir and I’m not in my clothes anymore. I shake my head, but that does little to wake me up. I’m not asleep anymore. I’m not leaving anything anymore. There’s no one-night stand. I’m just walking.

It’s still late at night, after midnight. It’s still raining. But I’m not leaving. I’m walking outside still and I’m not in my apartment, not in my bed. I’m wet all over and it’s not all from the rain. Sweat pools under my arms, my underwear cups a puddle of warmth, the drops clinging to my eyelashes don’t all come from the sky.

My arms hang loosely by my side. My hands are violent fists, I feel the sting where the fingernails have broken the skin to get to the blood below. I can’t unscrew the fingers and make them be fingers as much as I want to. My body isn’t mine anymore, not living in the present anymore.

I recognize the street and one of the restaurants I walked past from the one-night stand to the boy in my apartment. That was five weeks ago. This is now. My pajamas are soaked now, my skin wet with sweat now, my underwear damp now.

I wonder if I need to call the police to get back in my apartment. My apartment that I sleepwalked out of. I’m still now, I know where I am, and I know I need to make another call; I need to see the psychiatrist. I wonder how many sleeping pills I’ve taken.

I’m able to enter my apartment. I drip onto the carpet, just as I did back then. I was dripping on our last night together as a couple. I had ruined it, ruined us.

I wonder when I sleepwalked out of bed. I wonder if it was the same time I had left the apartment to cheat. In my apartment, everything looks the same. Maybe everything is the same. Something ghosts along my stomach lining. There’s nothing coming from the bedroom, but I can’t be too sure.

I feel unease as a single finger tickling at my spine. Everything looks the same and maybe that’s not a good thing. I want to rip out the carpet, burn the bedsheets, pour bleach over the couch—erase everything that the boy has ever touched. I want to peel away myself.

The bed feels like a place for only nightmares. Every time I go to sleep, he haunts. He’s turned my body into a conduit, him humming around my bones. I can’t go to the bedroom. He’ll be there, ready to slip inside my skin. But I can’t leave, I don’t have any other place to go. I think of my office, but the receptionist would come in and he would know that I’ve struggled to sleep. I can’t be a psychiatrist with no sleep.

I inch forward. The rain chatters against the window, and I could drown in it. Underneath is cold silence. I want my body to make noise, but even my hands are still, fingers spidering through the air. I grasp at doorframes, wall corners. Then my bed is in front of me, and I can’t differentiate between the curve of his body and crumpled bedsheets.

I turn on the bedside lamp. I squint. There’s nothing. He’s not in my bed. With the light, I become more aware of myself, of my wet pajamas clinging to my body. Nothing is taking up space in me. I only feel pain and exhaustion, and it is bone-deep.

I don’t want to peel away myself. But I do take off my pajamas, lifting away the smother of wet fabric. I leave them on the floor and climb into bed, leaving the lamp on, trying to keep my breath a steady, living thread under the rainfall.

(Your fingers tent together proudly before falling down in the sign for collapse. Sometimes it’s not a collapse. Sometimes it’s just the final break.)

I’d stayed awake after coming home from the one-night stand. He had woken up to find me drinking my second cup of coffee. The sun had barely broken free above the skyscrapers. He had known something was up looking at my face.

He asked what was wrong. I gestured to him: I cheated on you. My hands shook.

He didn’t cry. His eyes were slits, his mouth a grimace. He didn’t look like anyone I knew.

So, how was it? he signed, his hands still too brilliant, too sharp. I wasn’t able to make my hands describe it, I didn’t want to. I was immobile, coffee cup on the counter.

He stormed back to the bedroom. He came out again dressed and wouldn’t meet my gaze. I had nothing to convey anyway, not even shame. The only sound of him leaving was the door slamming shut, a final crack of thunder, the sound of the end.

Have you thought about taking a week off?

I’m staring at the cuts in my hands in the psychiatrist’s office. I’ve just told her about my fitful nights, my sleepwalking, and the reasons behind them. She’s warmer and more straightforward than the cold steel I expected; no notepad perches in her lap and I’m sitting on a worn loveseat.

Not really, I look up at her, meeting her steadiness. My clients wouldn’t be happy.

She shrugs, Your mental health is important. It’s important to take time for yourself too. If you’re not taking time for yourself after ending a stressful relationship, that manifests into a more serious problem. She lets the words take root. I keep thinking of him, his hard gaze and bitter mouth before he left, and I want to make things right. I want to tell him why I did it, not to hurt him, but to help him, help me, help us. I want this to be put to rest.

Outside, the rain has thinned to a fine mist, the kind that hangs more than falls, drawing close into my space. I hurry through it; it feels like a whirl of unsettled dust. Taking off my raincoat in the car feels like peeling off my pajamas after that sleepwalk. I suck in breath after breath, trying to dislodge the shard of memory in my throat. There were things that had bubbled to the surface and I wonder now if my hands had conveyed those buried moments.

I start the car. The rain coats the windshield. My hands remain a mystery.

I’m going to apologize.

I stand in front of the mirror. I gesture to my reflection. I’m sorry I hurt you. I’m sorry I hurt you.

I called the receptionist and told him I was taking a week off. I was ill. I told him that I would email clients and I would be available in case of an emergency. His responses sounded measured, his voice careful. I hope you get better, he said.

Hanging up, I thought back to his glittering eyes and wondered if it had been the light instead of him. Or if it’d been me, wrecked with nothing to control.

I slept away the two nights until Wednesday safe and sound, each and every sleeping pill dutifully swallowed. In the morning, my underwear would be dry but I would still feel the sorrow behind my teeth, below my fingernails. I needed to let it out.

I’m sorry I hurt you. I’m sorry I hurt you.

I go in the bar and I see the cluster of gesturing students almost immediately, as if a magnet there draws my gaze. Then I see him, hanging back like he was when I met him. My determination snowballs, I want to leave but I force myself to go over to him. He looks the same, but it’s only been just over a month.

I touch his shoulder. He recognizes me, and his gaze doesn’t soften when I gesture to him. I need to talk to you.

He doesn’t want to go outside; that’s where the smokers go to suck down another cigarette. I follow him in the bathroom and he turns to face me, cross-armed by the sinks. My hands shudder with the words to come, and my reflection above the sinks looks pale, leeched of all color by the sink lights.

I’m sorry I—

He shakes his head. Stop it, he says, his voice clipped.

No, I want to—I need to do this, I sign need, my index finger a hook plunging down.

You need to do this? For who?

For us.

Us? his eyebrows tent in disbelief. He shakes his head again. There’s not an us anymore. I’ve moved on.

I try to explain, It’s not like—

Then what is it like?

My hands scrabble and grasp at air. I’m trembling all over, but I try to sign again even when my fingers won’t stop shaking.

I didn’t want to hurt you—

His hands clap over mine. I’ve moved on, he hisses. You should too. He’s close enough to kiss and then he isn’t, moving past me. I watch in the mirror as the bathroom door swings behind him. The shard of memory is back in my throat, and it cuts at my heart too. I can’t cry, there’s a dam blocking the way out.

I walk out of the bathroom, turning back to the cluster of ASL students. I want to see him again. I want to watch him and see if I can find the person he was before, before I ruined him. But I don’t; I see the receptionist instead. I see the receptionist smiling and signing to the boy, the hunter and the game. I see the receptionist signing in ways that I couldn’t, expressing himself in ways that I couldn’t.

The boy had always said our relationship made him anxious, a word he signed simply by shaking his hands in front of him. He worried about us communicating, and I would always soothe him, sandwiching and rubbing his hands between my own. I had never understood the anxious sign until now, until I had my feelings stopped up inside me with the clap of his hands. I can’t breathe until this is over, but this is never going to be over.

I’m unable to look away from them together in the bar, the receptionist and the boy, and I know I will dream about this. I want to leave, but I can’t move. I don’t know if I want to move. I can only stay stuck in the shadows of the bar, hands trembling with everything I’m unable to give.

Audio Recording of Ross Showalter Reading “Night Moves”