Sarah Rose Cohn Bennett is a writer and budding psychotherapist from Syracuse, New York. Sarah spent the past year on a Fulbright scholarship in Wałbrzych, Poland, and now lives in Columbus, Ohio, where she is working as a therapist and keeping her eyes peeled for Hanif Abdurraqib (he could be anywhere!). Her poems have appeared in Pithead Chapel, La Piccioletta Barca, Stoneboat Literary Journal, and are forthcoming in Watershed Review. You can find her on Twitter @SRB926 and Instagram @sarrose_.

I picked up First Love, Last Rites by Ian McEwan at a used book stand in Warsaw, Poland. It was the only English book available and I needed something to read on the train. If you’re unfamiliar with the work, I’ll briefly describe it here using some of the author’s own words: “The business was to find a boundary, then cross it” (The Guardian, 2015).

McEwan is undeniably a talented writer—I’m a fan of some of his other works, and these erasures are not meant to cast a categorical judgment upon him as an author. Notably, McEwan makes it clear that he intended this collection of short stories to, in part, explore a realm of the “taboo,” and therefore to elicit a sense of disgust, discomfort, even horror, in the reader. In this sense, my response is in alignment with that effort.

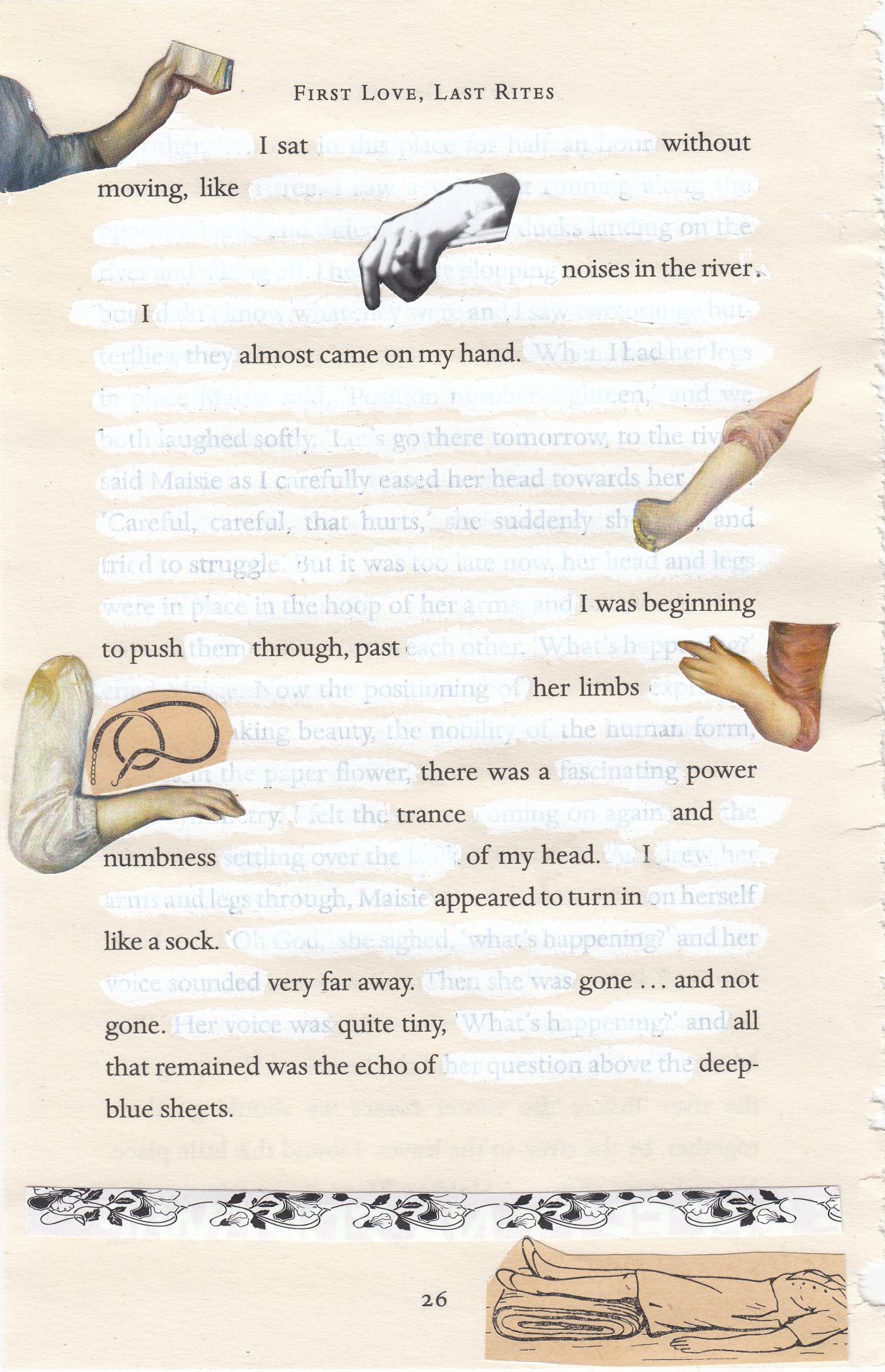

What doesn’t sit well with me is that this author—this male author—felt confident writing plot after plot forcefully decimating/dominating/disappearing the female body, for the sake of, what, crossing boundaries? Pushing back against the prude-ishness of modern society? Of what we might refer to today as cancel culture? I know there are more thoughtful ways of achieving that because I see it myself in the comedy I consume, the literature I consume (think, Toni Morrison), the visual art I consume, where boundaries are pushed, and sometimes the consumer is made to feel uncomfortable, even ashamed, even disgusted, and it’s worth it.

When he wrote this book, who did he imagine reading it? Did McEwan, can McEwan, imagine what it might be like for a young female reader to swallow, take on, really feel his stories, in the way that you feel what is written because you remember, you know, this character could be you, or has been, or might be? And this is not to say that I am in protest of being moved by literature toward discomfort, disgust, or shame—but in this collection, we are given no catharsis. It is senseless in the way the horror of the world can be senseless. And if that was his point, I’m just not interested enough to feel as awful and naked as I did on that train ride where all I really needed was a good book to get me home.

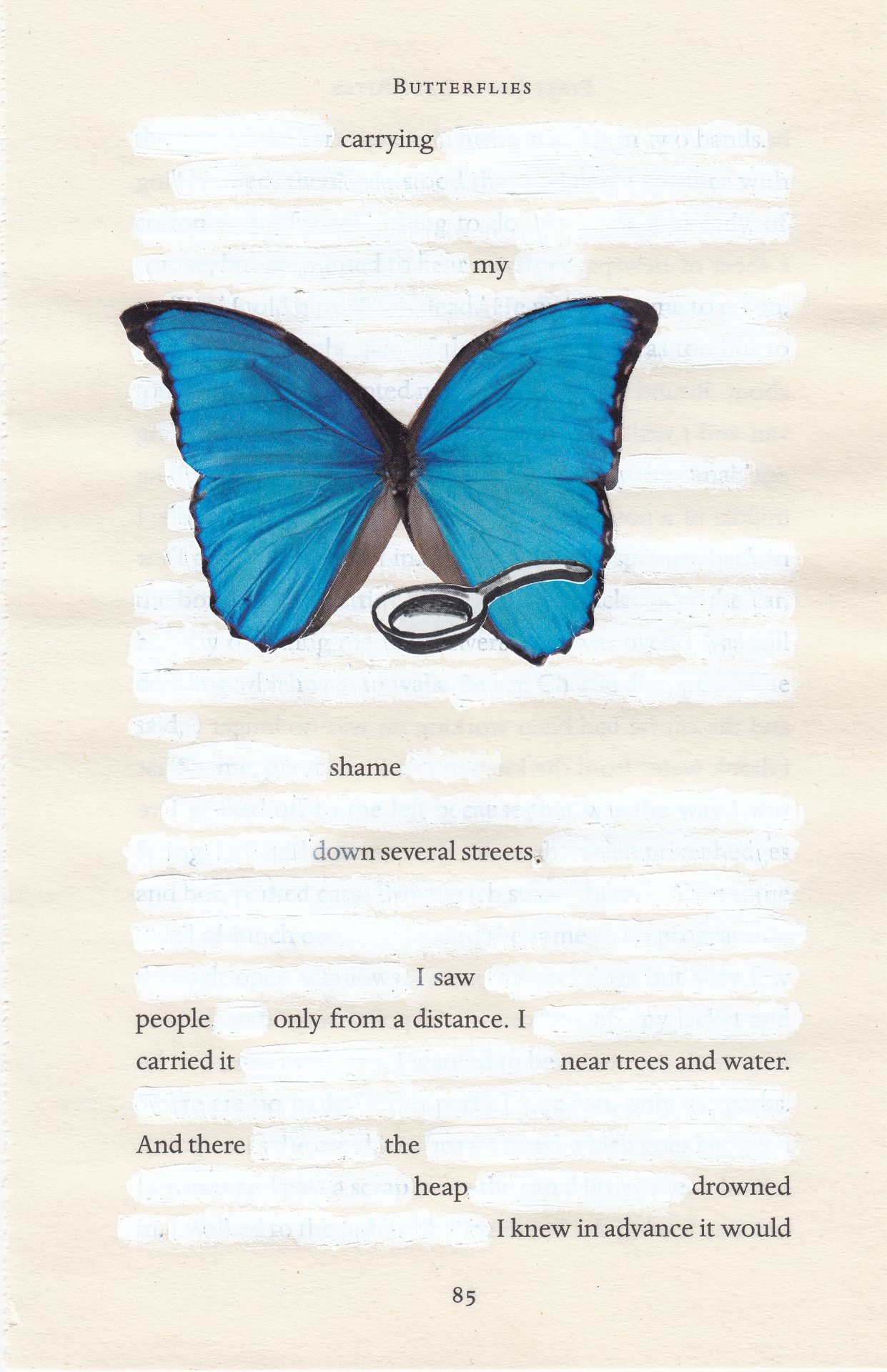

These erasures were born in the aftermath of reading this collection, half in an effort of reclamation, half from a less tactful place of spite. The “I” in each piece refers loosely to McEwan and/or his male characters, and/or the patriarchal messaging that informed the righteousness of this book in the first place.

For the erasure as medium, I am indebted to poet Mary Reufle, whose white-out erasures, particularly her collection “Melody,” have moved me again and again.

Guardian article in which McEwan discusses his book: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/aug/28/ian-mcewan-first-love-last-rites-40-years-since-publication

<<<

>>>