Four Short Poetry Reviews

Reviews by REILLY COX

Marginalized experiences are constantly, brutally, consistently conflated, both between communities and within them. POC, queer, dis, poz—whatever the experience, it is assumed that one experience equals another of the same name. This is, in part, a failure of language. This is, in another part, a failure of simplification. Narrow the view. Take out the mess. Make me pretty.

So how am I to say what unifies these reviews? I read them because they are unlike anything else. Hybrid, or erasured, or reclaimed, these works not only grapple with the variety held within the trans experience but show the many wonderful, frightening ways that writing can reflect life. Some are sophomore collections, some debut. All engage, in one form or another, with extant texts. All, in one form or another, queer or shift their respective genres, should they be beholden to genre at all. And I would recommend all of them.

i cant stop riting tran: a review of Jos Charles’ feeld

Early into feeld a section concludes, “thomas sayes trauma lit is so hote rite nowe” (Charles 11) and many would say that thomas is right. A peer of mine, upon discussion of a colleague’s collection, stated, “All contemporary poetry is just trauma porn.” I’ve been fascinated by that idea since hearing the claim. There certainly is an exploitation of emerging writers who choose to put forth their traumas in writing that they might not necessarily want to stand by later in their careers. One also does not have to look very far to find a collection—oftentimes debut—that centers on some form of trauma. But to dismiss it as “trauma porn” or as some “hot[e]” trend reveals an impulse to dismiss the traumas of others (both other people and othered people) as performative, exaggerated, or boring.

This becomes further complicated in trans narratives due to the complication of trans traumas. Is the experience of a forced boy/girlhood not a form of violence? With a medical community that is at times borderline medieval in their approaches to and views of trans patients, should one still desire gender-confirming procedures? And if everyday is an experience of historical and language-based erasure, how can a trans individual build towards anything at all? This last trauma—the trauma of language and history—is at the root of feeld, in which Jos Charles uses neo-Chaucerian language to form a text that encompasses argument, poetry, and loss. As she writes, “i care so / much abot the whord i cant / reed” (33).

In terse, broken entries, Jos Charles wrecks me. The setting of the text is in the titular “feeld,” where “tran” at once finds a place of refuge, of persecution, and of absurdity. In one moment, we have a beautiful image: “the mothe bloomes inn the yuca” (24). In another, a plea: “stop caling me he” (41). And there is humor! Jabs at God and moments of defecation and the emasculation of cocks. Yet the humor hides violence. Charles writes, “this / is the corse / a tran / / a feeld / a corpse” (3) and in that slight moment we find both a formula for the text as well as one for a common trans experience: the course of finding one’s trans identity, entering the world, and meeting an ultimate violence. Yet the collection is not fatalistic. Just through the act of reclamation of language and history, Charles offers a starting point forward through the feeld.

It is a brief collection, spanning a little over sixty pages, to its benefit, as (like The Descent of Alette) it is a collection that begs to be read aloud. In part it is for practical purposes—the spellings and constructions are anything but standard—but there is something songlike in the feeling of forming a language that is at once familiar and strange. So I would recommend feeld, and I would recommend taking in into your mouth, and letting out the song of it.

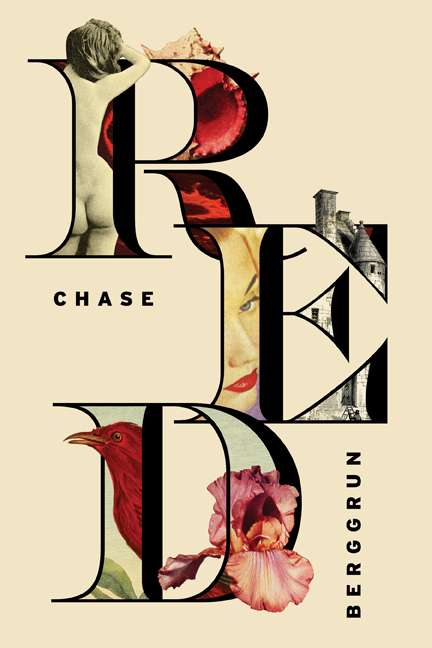

I am a wife he fashioned by his own hand: a review of Chase Berggrun’s R E D

I have, admittedly, been excited for Chase Berggrun’s R E D for awhile now. An erasure of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, dedicated to the victims and survivors of domestic and sexual violence, R E D queers Stoker’s famously misogynistic and (multi)phobic text into something terrifying and wonderful (BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA). “A Note on Process” at the beginning of the book describes the formal constraints of Berggrun’s erasure of Stoker’s text, gives a framework for what emerges over the next sixty pages, and an acknowledge of the concurrent occurrence of Berggrun’s own gender transition during the making of this erasure. According to the note, “As they were discovering and attempting to define their own womanhood, the narrator of these poems traveled alongside them.”

Who is the narrator in the text? They certainly are not Jonathan Harker, whose frantic and hateful letters and diary entries composed much of the narration of the original text. And they are not Berggrun, who distinguishes themself from the narrator (but who would probably feels a connection to that narrator, who opens the collection “I was thirsty / I was a country of queer force” (Chapter I)). And the plot seems more linear than collections like A Humument, whose protagonist Toge is much more adrift and coincidental than the reclaimed protagonist and narrator of R E D. So who are they?

In erasure, there is extant text from which the erasure derives, the newly created text from what the erasure leaves, and what I call the “intertextual text,” that which exists unpublished but understood—a conversation unspoken—between the extant and the newly created. So because erasure involves a layer that is unsaid and impossible to define, it is difficult to define the plot and narrator of most erasure collections. R E D, however, frames the narrative in the femme, the reclaimed, and the abused. So we know that much about the narrator, who develops as a companion under the thumb of a charismatic but violent and wretched partner. This relationship culminates in their shooting of their abuser in self-defense: “Red upon my face / My eyes followed the falling snow / He died” (Chapter XXVII). So in the extant, a group of vampire hunters slay a vampire lord and his servants; in the newly created, a victim frees themself but at the cost of further violence; and in the intertextual text? The in-between?

It is also a gorgeous book. The cover features a beautiful collage by Zoe Norvell; the interior design by Michael Newton is impeccable, starting with the red, heavy paper that precedes the title page; and the retyped erasures give greater weight but also more breath to Stoker’s language, as reclaimed by Berggrun. I’ve found myself returning to it again and again, both for the queering of the high language as well as for the design itself. I look forward to seeing what Berggrun does next—perhaps Frankenstein could be a sophomore project.

the parachute in the field / shivered : a Review of Ely Shipley’s Some Animal

I found myself –broken while reading Ely Shipley’s second collection, Some Animal. Heartbroken, lungbroken, backbroken. How could I not? Whether from laughing or horror, it steals the air from me. Whether from writhing or weight, it bends me backwards. And my heart, my heart…

The collection opens with a scene of teenagers with petals on their tongues, waiting to see if the petals are psychedelics. “I’m fourteen with a red petal on my tongue,” Shipley writes. “I want / to see—I’m not sure what—a miracle.” (“Playing Dead”) Though unnamed at the start of the collection, the miracle becomes evident as we continue through the text: the miracle of escaping one body and entering another. The how is variable. In some cases, the escape becomes enabled (or prohibited) by extant texts: the poetry of Ovid, Shelley, Keats, and Dickinson; medical writings on sexuality, gender, sleep, blood, “hysteria,” and more; charts on UFOs; etymologies and folklores; music lyrics; and more. What forms is a library, both for and against dysphoria, that terrible beast. For those unfamiliar with the term, dysphoria, specifically gender dysphoria, is the distress a person feels due to their birth-assigned sex and gender not matching their gender identity. It can result in emotional, physical, and psychological symptoms and, in this gender-binary-centered society, can be set off by simply moving through the world.

The collection itself transforms page-by-page, blurring from prose-structured essay to textual collage to multi-sectioned poetry, a chimera of sorts. Whether to replicate the fragmentary experience of living with dysphoria, to reject binaries (genres), or to simply use the most necessary form and content for any given page, Shipley creates something that devastates and amazes. Some Animal could well serve as the foundational text of a course, both for its breadth but also for its engagement with primary transgender experiences: the struggle with one’s body (“Playing Dead”); teenage trysts and reclaimed years (“A Sweet Teen”); the bizarre and infuriating experiences of living in a society with gendered spaces (“On Bathrooms”); or finally the historic basis and surreal interactions around secondary sex characteristics (“On Beards: A Memoir of Passing”). Nightboat Press, who put out Some Animal, has chosen an amazing text to share with the world, and Ely Shipley has my eternal gratitude for writing it.

Farm means thirst: Review for If the Color Is Fugitive, by Sara Mithra

Julian, née Sara Mithra (and the name under which they are published), received a Masters in Folklore Studies at UC Berkley. Those two points—of naming and folklore—feel vital to this collection which so directly engages with heritage, language, and story. It is a making and an unmaking, a yes and a no, a yarn unraveling. When we open the collection, we read “Ides of March,” a poem about the slaughtering of buffalo. Beware, beware, beware, you beast. You “breach born…too early come.” (15) You “low / low / low / ing” mass to mow down. The hunters have come in locomotives to shoot you from the window. The senate has risen up and taken their blades from their togas. The prairie is a massacre. No matter which crime the title refers to, the collection opens with a clear warning: beware. In “Questionnaire,” when Spinsteress, a wizened figure who “soaks blisters in salt” (19), is asked whether her farm represents “heritage / or the taming of the West,” she answers, “Farm means thirst.” Rather than this Manifest Destiny bullshit, this Little House on the Prairie perfection, we enter a West of thirst and death—one that changes a person, especially if they try to change it.

As the collection continues, it becomes more surreal, the landscape more strange, the people less Figure and figured. In “The Fifth House,” an unnamed speaker tries to find stability in houses built from various materials—hay, planks, clay, iron, and at last paper. “Come hurricane, flood, drought, or wildfire; / I pray a page escapes—one corner of a page. / One phrase.” (40) Note that it is not a prayer to avoid destruction but that some remnant survives the destruction, one phrase to serve as witness to the flood or conflagration. From my understanding of Mithra’s folklorist work, there is a focus on that documentation that is at the margins, the documents and marginalia that holds the truth, the questionnaires and corners of pages. For so long, the margins have been ignored for more popular, whiter, cleaner conceptions of Nature and the West. But, as Slavoj Žižek famously claims, there is no such thing as Nature. We are not separate of it. We are of the refuse and detritus, with binaries abandoned for the violence they enable.

As a debut, If the Color Is Fugitive is concise yet sprawling, careful with its language as its language works to collapse. A reader would do well to give space between its poems, with each containing a world and characters and speech so vivid and distinctive that I have a hard time entering back into this world when I place the book down. The poems surprise and break; the arcs rise and fall; and we find ourselves in a new space, both threatening and lovely. I am excited to see what Julian does next—check out their Vimeo and Soundcloud for some bizarre and brilliant recitations and collages. And pick up their debut, before it destroys itself.