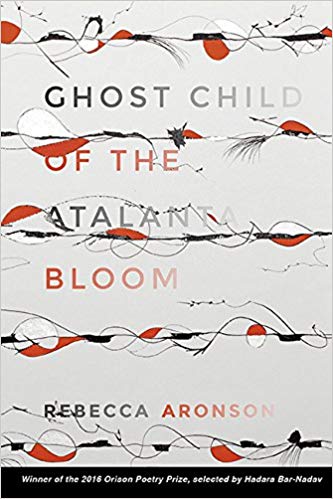

“It was the kind of fever in which want burns”: A Review of Rebecca Aronson’s GHOST CHILD OF THE ATALANTA BLOOM

Review by REILLY COX

Story teaches us that, when it comes to our demise, we have options. Accounts differ. Homer is killed by either a turtle dropped by an eagle or by a riddle about sea lice. Alcmene, after her death, is either turned to stone or buried with family. Lazarus even had the bad luck of coming back only to either sail off and become bishop or get captured and beheaded in a cave. In the meantime, though, there is joy: Homer enjoys his walks; Alcmene gets a permanent honeymoon on an island; Lazarus laughs at clay.

Aronson’s newest collection could then be taken as a sort of education in want and the endings want brings. We might have fun setting the field on fire but we’re still in the middle of it. The city might be burning but “[no] one will say it’s time to leave.” We might be proud that our bodies might keep out bacteria, but we carry in us a history of cancer. And that’s fine. We’re enjoying ourselves.

Throughout the collection, Aronson balances two views of the world: one in which the world is bursting with life and one where the world is a collection of remnants. Bluebells and birds sit adjacent to shards of pottery, or buried cities. Past the garden, there is always an apocalypse happening, some city ruining itself. The rain that makes the flowers bloom is, somewhere, creating a flood. Even if we might manage to contain something—in a museum or aquarium, a body or drawer—it’ll come unleashed.

We could take this collection as a series of 46 lessons, from brewing tea to burying parents to changing our body into another. But then the lessons often divide amongst themselves—“Flood” and “Flood, Postscript,” “Dream 1” and “Dream 2,” the many assorted and invented museums. The poems speak and echo to one another, sometimes to repair damage done by a predecessor, sometimes to destroy something to which we risk growing attached. And we build towards that joyful state.

It is rare that any one image takes up the space of poem, or that it doesn’t transform half a dozen times before the concluding line. In “Wish,” the body becomes a shield becomes arrows becomes a circling animal becomes a person prowling through a house becomes ice becomes a bird, and it works. We do not lose track of the narrative. The spell doesn’t break, even after we look up from the page, blinking. The imagery moves and keeps us moving through it, towards that final moment, the titular poem.

That poem begins and ends in light. One light is the light above the poem: “This is what it’s like to be the sun, hovering / above a rising and falling sheet / draped on the body on the mattress.” The other light is the light below the poem: “the ground glows as if lit from within. / A night like that. / The light like no light we knew.” Between those lights, we move between different ruins–of lovers, of parents, of cityscapes and gods and gnats in wine glasses–and it’s all right then. It’s okay. Even our ruins will be illuminated, brightly, brilliantly.

In our final moments with the collection, the imagery established so far breaks down into little pockets of worlds, shards of histories left to echo one another. In that echoing, we receive the burdens of those other shards but also their salvations. If we must bury a parent, let it be in that Etruscan tomb. If one marriage is childless, we can give them children running by rivers. And if Atalanta, virgin huntress tricked into marriage, must be cursed into a beast for it—so she might never touch her lover—then let us give them the opportunity to consummate, if only in a poem, and then gone again.