“…time as a kind of language … allows me to organize the logic of a story.”: An Interview with Shastri Akella, author of “Reva Speaks a New Dialect”

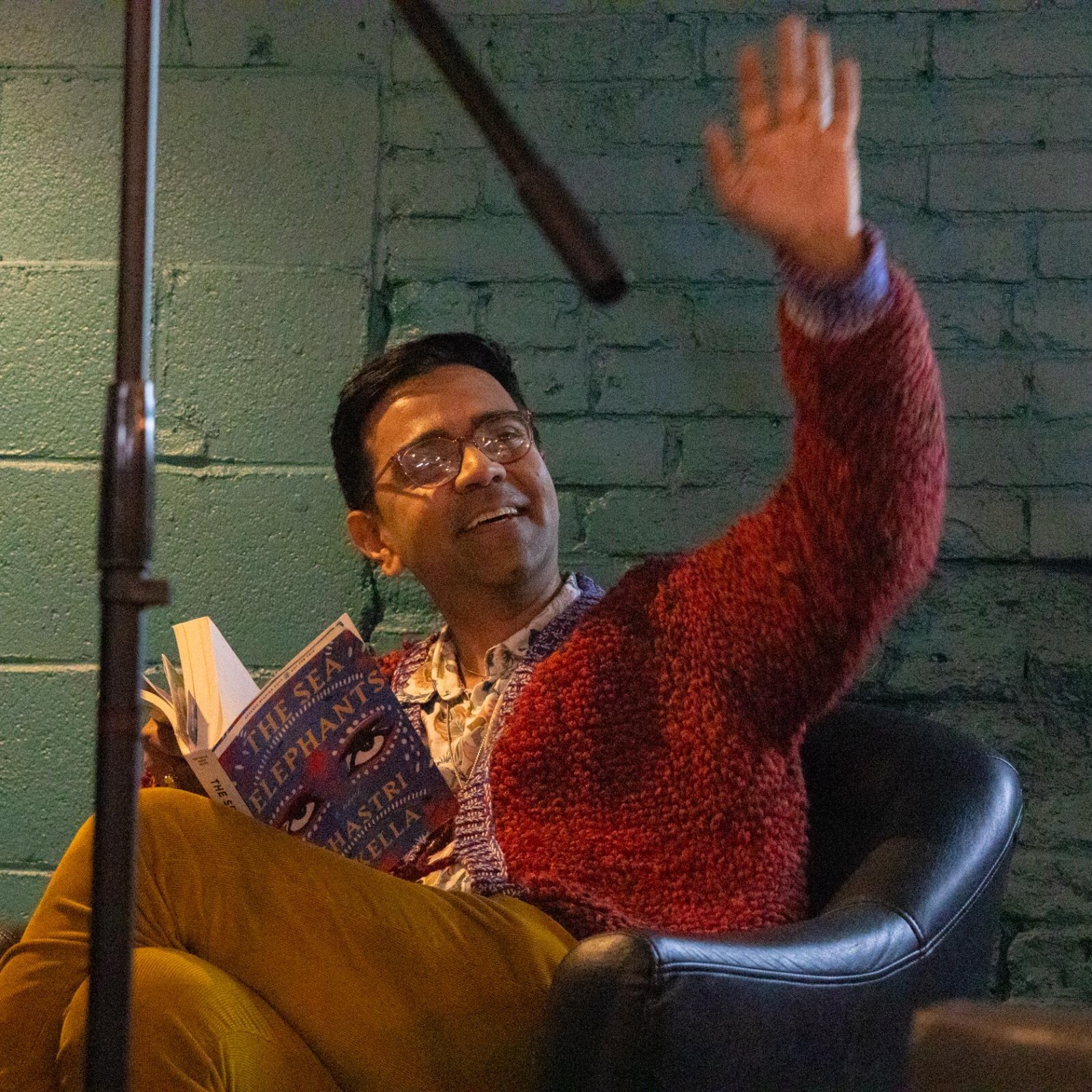

Chinaecherem Obor, Editor-in-Chief at Black Warrior Review, interviews Shastri Akella, author of “Reva Speaks a New Dialect,” runner-up in the 2024 BWR Fiction Contest.

Chinaecherem Obor: In the time since your story “Reva Speaks a New Dialect” was named runner-up by Chigozie Obioma in the 2024 Black Warrior Review Fiction Contest, another story of yours, “What Trevor Saw” has made it into the 3-story shortlist for Galley Beggar Press’s Short Fiction Contest. Congratulations on both honors! In the titles of both stories, there are namings. However, while Reva speaks, suggesting agency, the second title puts emphasis on an unnamed thing that Trevor saw. When you decide on titles for your fiction, what are some of the effects you want them to achieve in your reader? How much influence do you think a story’s title has on the expectations a reader has going into a piece of fiction?

Shastri Akella: Thank you very much! They are both contests that I deeply respect, and that I’ve been submitting my work to for around six years now, so I am grateful to see that my stories have resonated with astute readers like yourself and Eloise, the editor at Galley Beggar Press.

My goal with titles is to come up with something crisp that (a) is intriguing and (b) captures something essential of the story: a narrative emotion or a transformative moment for a character. In it’s capacity to create intrigue, the title invites the reader into the narrative world, and during or after their engagement with the story, readers will notice that the title resonates that moment or emotion it is emblematic of, and that noticing, it is my hope, will amplify the story’s affect.

Chinaecherem: Also, is it too nosey to ask what it was Trevor saw? Should I just chill and wait for when the story is out?

Shastri: Trevor, a British expat, traveling through India and photographing its people, crosses paths with Gagan, a twelve-year-old Dalit child who assumes Trevor is a friend. The illusion is shelled-open when, years later, Gagan sees Trevor release a book of his photographs (titled ‘what Trevor saw’), and this includes images from a disturbing moment in Gagan’s life that he didn’t realize were photographed—and now they’re up for public consumption. In leaning into the child’s point-of-view, I bring humor into the narrative for reasons I expand on in answer to the next question.

Chinaecherem: One of my favorite things about “Reva Speaks a New Dialect” is the humor. For a piece that is contextualized within the politics of a caste system, the atmosphere is wry and dry, sometimes straight absurd. All without losing any of the emotional heft of the story. Do you go into the writing of certain subjects with the intention of creating some humor out of it, or do you think some subjects more than others lend themselves to absurdity?

There is a striking moment in the film The Florida Project where the eight-year-old Moonie, raised by a single mom in extreme poverty on the outskirts of Disney, brings her friend to a wild pasture where cows are gazing against the backdrop of foreclosed houses in ruins. And she says, “Look, this is our own private safari.” They have created for the duration of their game an experience they cannot afford. And in doing so they have stripped this thing, that is out of their reach, of its power to make them feel left out.

As someone who grew up in a working-class neighborhood, humor similarly allowed me to create a brief cushioning between myself and reality, so when I re-entered the real, the things I had no control over could no longer hurt me, even if it harmed me.

In stories, when characters make room for humor in situations that are inherently grave, it becomes a way to ascribe agency to them, to expand them, and to make them larger than the very realities that want to make them feel small.

Chinaecherem: There was a line from “Reva Speaks a New Dialect” that struck me. After a younger Reva admitted to being hurt by some lore about her birth shared by Amma, the latter had a rejoinder: “I’ll tell you every night…. One day it’ll stop hurting.” Do the telling and retelling of painful stories really take the sting away from them? Or do they simply re-open scars? Do stories give us more than they take, or is the reverse the case? Are there stories you find yourself coming back to again and again, either for comfort or to tame the power they have on you?

Shastri: There is, on the one hand, Story: narratives from mythology and folklore are a prime example of it. Re-experiencing or re-telling, in such cases, does not tire its emotion and it can in fact be a way for us to, in the safety of a familiar cocoon, bring our emotions into the open, and in affording us such an opportunity, Story is deeply giving.

And then there are stories that are inflected on us: the ones that are told by those in power, meant to keep us small, and the ones that are passed down in families, the beating heart of intergenerational trauma. Looking such stories in the eye with patience and courage can, I believe, snuff out the power they hold over us. And that is the gift Ganga gives Reva.

The story I return to every year for solace is The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy. It is my birthday gift to myself, one that is a powerful refresher on how stories can simultaneously carry the effervescence of a childlike wonder and the power of wish-granting demigod.

Chinaecherem: I do find it interesting that the story does keep returning to the secondary timeline set in the past, the one where Reva is young and hurting from Amma’s stories, but “[o]vertime, Amma’s stories stopped hurting.” How does time function in your writing? Many non-Western interpretations of time are non-linear, and events have ramifications beyond their chronological timing. Do you think setting a story in the past versus the future—or vice versa—has any bearing in how the narrative tension builds up?

Shastri: ‘Reva Speaks a New Dialect’ had precisely that intention of breaking the chronological experience of time. Reva is sixteen when she has to, by way of marriage, leave a familiar world and start to cohabit, essentially, with strangers. The one thing she knows—the one solid ground—is her relationship with her mother, something she returns to—and that returns to her—as she sees the present, considers what she wants from it, and ascribes meaning to it accordingly.

As a writer I see time as a kind of language, one that allows me to organize the logic of a story in a way that allows readers to humanize characters they are meant to care for (Reva in this case), even as it shows the past not as a place we leave behind but a landscape that we hold within us, however far we go. I truly think the prejudice we hold for a community we know nothing about can be uprooted through Story which allows us to experience the many times of an individual in that community, the sheer mythology of their personal.

Chinaecherem: Your debut novel, The Sea Elephants, was described by Ellie Eberlee writing for The Massachusetts Review as “embrac[ing] multiplicity—of plurality and plenitude across an interminable spectrum of sexuality and gender.” What writers and texts were your literary companions during the writing of The Sea Elephants? Were there noteworthy influences that helped you shape the thematic and craft leanings of the novel?

Shastri: The main character, Shagun, is a street performer, who enacts stories from Hindu mythology, particularly the ones that have been, over the course of translations, been censored or deleted: Chitrangada, for instance, an important transgender character in The Mahabharata, one of the founding epics in Hinduism, is absent from nearly all translations of the text into regional languages. So I revisited mythology in the original language (Sanskrit) and in folktales, particularly as told by those of the Dalit caste and the trans community, because the censored and forgotten characters found life and preservation in their narratives. The myth of Iravat, the six-tusked elephant surfaces several times in the narrative. In this case, I took the source material and brought my own spin to it so it becomes an allegory for intergenerational trauma.

In terms of more contemporary fiction, along with Roy’s novel that I mentioned, Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay was a key influence: the way it uses comics as a framing device taught me how to use myth within my novel.

Chinaecherem: What are you currently reading?

Shastri: My second novel that I am currently working on is a work of fantasy, so I have returned to Ursula Le Guin, and I am doing a close-reading of her Earthsea Quartet. One of my favorite contemporary writers is Mariana Enriquez and I am mesmerized by her recent collection, A Sunny Place for Shady People.

Chinaecherem: Thank you so much for your brilliant responses. And congratulations once again on placing as runner-up in the 2024 Black Warrior Review Fiction Contest.