45.2 Feature: Craft Essay by Ava Hofmann

Originally from Oxford, Ohio, Ava Hofmann is a writer currently living and working as an MFA student in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. She has poems published in or forthcoming from Black Warrior Review, Fence, Anomaly, Best American Experimental Writing 2020, Datableed, and Peachmag. Her poetry deals with trans/queer identity, Marxism, and the frustrated desire inherent to encounters with the archive. Her website can be found at www.nothnx.com; she also overuses her twitter account, @st_somatic.

Writing, History, and Frustration: On “three charms for the revelation of secrets”

The archive is a frustrating place.

The encounter with the past is defined by that which cannot be encountered, the reality of the lives and experiences which will never return. Queer people have existed forever, but any evidence of them in the archive is precious, because so often our histories were destroyed, or simply could not be preserved in a culture that was defined by its homophobia and transphobia. Think, for example, of the Nazis’ public burning of the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft’s archives, the intentional destruction of some of the earliest research into and advocacy for the experiences of gay and trans people. This archival spottiness is why some queer people often imagine histories for themselves—at least, I know that I can be prone to speculation on historical figures’ queerness, trying to find trans representation in the cipher of historical texts.

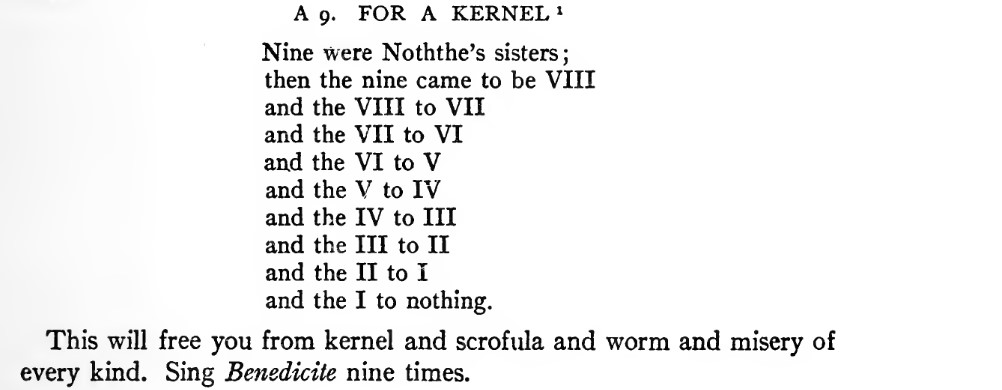

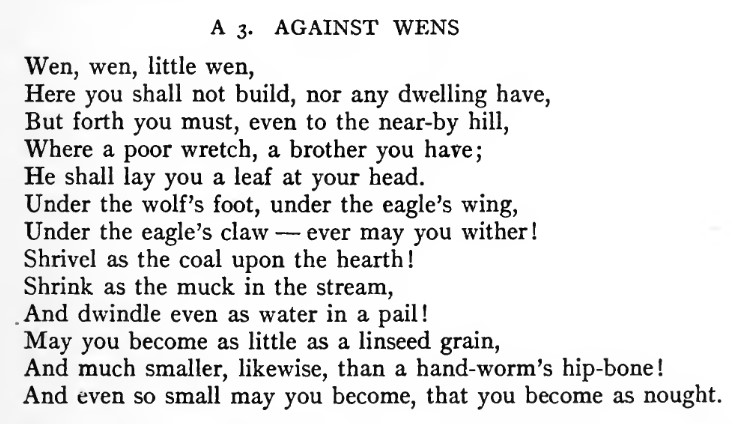

The spring before I came out, I was reading poems from Felix Grendon’s 1909 translation of the Anglo-Saxon charms. The Anglo-Saxon charms are magical healing spells written in the form of poems trying to invoke transformation in the world or in one’s body. The way these Old English poems instrumentalized poetry reminded me so much of things which I valued in the current literary moment—the implication of the reader into the space of the poem, a commitment to strangeness, the possibility of transformation:

But I also found these poems deeply frustrating. They offered strangeness and transformation, but not the strangeness and transformation I needed. Why did it have to be that reducing nine sisters to nothing produced healing? Why couldn’t these texts be part of an embodiment that was more like mine? Or, better yet, why couldn’t these poems tell me what my experience of embodiment actually was? The research began to stand in for my own desires, the gender dysphoria I had repressed for years.

This frustrated research incited in me the need to write my own poems in the style of the Anglo-Saxon charms, to re-imagine and re-write history so that I could survive for just a little while longer, maintain the façade just a little while longer. But what I had buried for so long surfaced in the poems: images of crossdressing, gender transformation, the possibilities I had kept myself from out of fear and a misguided desire to deny myself of the things I needed.

In the summer of 2017, in large part due to the incredible kindness and acceptance of my community of friends and writers, I came out to myself, and then the world. About a month later, I wrote the first draft of “three charms for the revelation of secrets.” Finally, I could use the form which had been frustrating something in me to articulate the transformation I needed, the threshold I needed to cross. What was basically an academic exercise became deeply personal; the abstraction of a magical glyph hinged open into the space of being a symbol of my own desires. I think all this taught me something I really value and desire in poetry and in life: the capacity for forms to be altered, the capacity for poems and queer people to rot genres and forms and symbols from the inside—and thereby create new possibilities.