43.1 Feature: Craft Essay by D. Allen

D. Allen (http://thebodyconnected

On Material

by D. Allen

We writers often talk about material. Remember that time you fell into the river? It would make good material. The interview went well but it didn’t give me enough material. I overheard some good material when I rode the bus on Tuesday. I’ve gathered so much material that I don’t know what to do with it all.

As a poet and an interdisciplinary artist, I want to talk about embodiment and material, the kind we must explore with all of our senses, not just our minds.

First and foremost, my own body is my material. I don’t just write about my body or from my body; my work physically alters my body, and my body gives physical form to the work. Sometimes my work involves performance or other forms of documented embodiment; I’ll alter my body by having someone affix thorns to my vertebrae with wax, for example, then take photographs or video or sound, then write and make other images based on the experience. Or I’ll ask the MRI technician not to put any music in the protective earphones while the machine is working, so I can pay attention to the sensations in my body and document them later.

My primary work-related research requires me to be awake to physical sensations and take notice of the experiences that lead to those sensations. Because I have a connective tissue disorder that causes chronic pain and injury, these sensations are often unpleasant. Chronic pain puts my nerves on high alert so that sensations other than pain, which I ordinarily wouldn’t notice, become magnified. Somehow, interpreting these sensations as research for my creative work has become a survival tool. Pain becomes material.

I think a lot about the metaphorical implications of having a connective tissue disorder. My condition means that my body can’t produce collagen abundantly or correctly, which is like a glue that holds our bodies together and supports our skin, joints, muscles, tendons, organs. Without proper collagen, the skin and skeleton become too stretchy. The body has a hard time holding itself together.

With my body as my guide, I am always in search of other materials—objects—that will give the body pleasure and elicit a somatic response. Leafing through the velvety pages of antique dictionaries gives me pleasure, so I look up words even when I think I know their definitions already. I pick up rusted objects from the sidewalk when I’m commuting on foot, because the body likes that weight in a pocket, and the red flakes left on my hands afterward. I write longhand when the joints in my hands will tolerate it and I make visual works and music/sound works alongside the words because the body likes to see evidence of its expression in several different forms at once.

I defer to the body.

In “On Needles,” my lyric essay in Issue 43.1 of BWR, I write about all kinds of needles: sewing needles, hypodermic needles, tattooing needles, acupuncture needles, pine needles, etc. I write about the relationship each kind of needle has to my body.

This piece first emerged as a set of fragments, which looked to me like needles on the page; I then began to organize them into clusters. Some of these clusters are more narrative. One tells the story of the time a friend and I embroidered into each others’ backs with sewing needles, while others describe scenes in the doctor’s office or acupuncturist’s chair.

Other clusters are more lyrical and impressionistic. I am working to understand what a needle is and what it can do for me, and trying to find a pattern across all the experiences I’ve had. I’m trying to interpret the body by looking at it in relationship to a specific set of objects. I’m trying to understand pain and pleasure, and the difference between the two when both involve intense sensations.

After I drafted the essay, I started making drawings. I limited my media to India ink and water, and used only a single sewing needle (sometimes with thread attached) as my drawing tool. I didn’t look at the essay or think about ‘illustrating’ individual text clusters while I was drawing; image-making became another way for me to explore my subject matter, to try to understand its possibilities and limits.

When I’m creating work that has both visual and verbal components, I often think about an undergraduate class I took with Mary Lum, called “Traces, Mistakes, and Leftovers.” As a college student I was obsessed with the idea of perfection; I’m a pretty messy worker when I’m in the process stage of making art, no matter the medium, and I thought for a long time that readying a piece for presentation meant scrubbing away all evidence of process, so this class was revolutionary for me. We saved remnants from other projects in other classes and used them to make new work. We considered the value of half-finished sketches, cast-offs, and armatures as standalone objects, powerful in and of themselves. My relationship to materials changed forever after that.

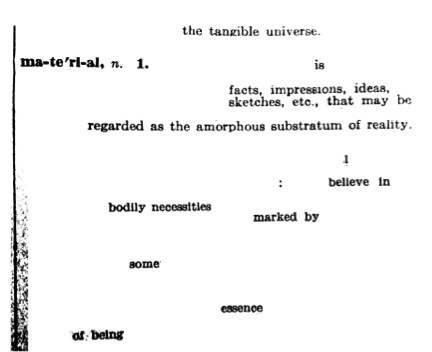

At some point while I was writing the first draft, I went to the dictionary and looked up needle. In my collection of old dictionaries, there’s one in particular—the Funk & Wagnalls Practical Standard Dictionary from 1943—that I use for everything, because its definitions for familiar words often surprise me, and it has these incredibly beautiful, sometimes strange, illustrations. So I worked with the “needle” definition as material, but instead of just weaving it into the text I photographed the page, then made an erasure poem out of it, which now heads the essay.

As a queer person with a disability, I often find myself remaking the world so I can live in it. I’m constantly shifting in my chair, putting cushions in the driver’s seat, putting my feet up, reminding people to use the name and pronouns that feel right to me, saying please touch me here and please don’t touch me here, not today. Making dictionary erasures feel like an extension of that daily experience. Just because a definition has been fixed on the page and established in our cultural lexicon doesn’t mean we can’t adapt it for our purposes.

My creative work is a way for me to investigate and repair the damage sustained by my body. Right now I’m working on a lot of projects that include mixed materials, most of which are part of a manuscript about connective tissue. I’m going back and forth between writing and making ink drawings, photographing found objects, altering photographs, layering paint and collage materials—and all of these elements are helping me think about my subject in different ways. By working in fragments and pulling all of these different materials into the same space, I’m attempting to reconnect the parts that have been physically separated, the parts that are in pain. I’m always searching for the specific materials that will remedy what ails me; that is to say, those that make me feel.