Review: VENTIFACTS by Christine Hume

Review by LAURA KOCHMAN

Ventifacts moves much the way that wind does—invisibly, winding around and across the borders of various subjects, making itself known through the physical evidence left behind: questions, memories, theories, stories, sounds, figures and facts. The name alludes to the book’s form, short pieces of prose that are remnants of thought. Hume sketches out a broad understanding of wind’s movement across culture and time, in climatology, government, health issues, themes in literature, mythology, philosophy, etymology, art. This is a book whose thinking lends itself to thinking about it in long lists. I try to accumulate my feelings. I try to articulate the invisible movement behind the evidence.

—

We start here:

The sounds we don’t recognize flying out of our huge mouths: curses of the furies, songs of the sirens, the babblings of Cassandra, all those horrifying sounds burbling up from a female body. The dreadful groan of the Gorgon sisters, whose name derives from the Sanskrit garg (think gargle or gag), a guttural animal wail that issues a great wind from the back of the throat.

Because mixed into the whirlwind of nonfiction research is an exploration of what it means to be a woman and make noise, or perhaps a depiction, or an avoidance of justification. I’m a little flitting and noncommittal myself. We begin with wind described as a female sound, the expression of something that others might call horrible or nonsensical. Wind isn’t just something we can see. We can hear it unless, as Hume discusses toward the end of Ventifacts, we choose to stay indoors and shut it out, creating a nauseating “sonic deadness.” Earlier, Hume declares “to control sensation is to betray it,” and then a few ventifacts later:

Beyond the wind, Herodotus and Pliny describe, is Hyperborea where people live in complete happiness for a very long time. I imagine this place suffocating rage, uncertainty, hangdog blues—the way in which I know myself. Whole emotional lives snuffed out. In windlessness lies our last chance of self-erasing.

The book spins around Hume’s relationship with her daughter—her daughter’s fear of wind, her daughter’s insistence on that fear—but I can’t ignore Hume’s position as a woman, and I can’t imagine that she would want me to. How, as women, do we pass down rules for self-expression? Should we? Is it harmful to tell a little girl that her expression of fear is invalid, or to try and protect her from the source of that fear?

—

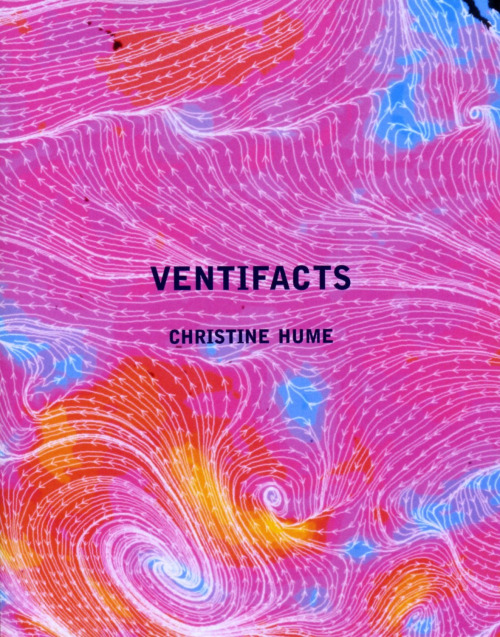

Hume doesn’t really give answers to the many questions that rove through this book, like wind, like borderless animals. In a book that deals in things we cannot necessarily articulate through the optic sense, this seems appropriate. The experience of wind is appropriate. We, readers, are appropriate. We can think about these things for ourselves. Hume resists controlling self-expression and conclusions, asking, “What do we resent more than a dependence we did not choose, one that mocks our dear individuality, our commitment to the singularity of our own stories?” The thing about wind is that it is powerful, and it sweeps us along whether or not we want to be swept along. It is a lack of control. A mysterious strong-arm from some unknown origin. It deals “its ordeal of airs, pushes on the spot, says decide amidst the shouting and thundering, skin all gooseflesh, dress billowing.” Hume suggests that wind is dangerous, wind is feral, wind is sublime, wind is feminine, wind is “sun cum,” wind is without borders. It’s difficult to pin down something without its own material existence, “to file the wind’s incarnations away neatly in the alphabet. Subject it to lists, taxonomies, archives. Try and try to house it, but wind will not be ordered or efficient. It won’t be accounted for. Not structured around human senses. Not serialized.” So the short prose pieces of Ventifacts are not ordered to fit a mapping. The cover image is a satellite map of wind, lines and arrows marking wind direction, color describing speed, and it tumbles into and out of tight spirals. It moves simultaneously, and this seems an apt image to describe the text itself. Because “to bring the sound of wind inside is to invite the eeriest waftings of vulnerability”—to admit fragility, a lack of concrete answers and linear thinking. To invite the fearsome wind is also to accept these things, to sit still and think about them until the invisible force dies down, until you can gather and examine what’s been left behind.