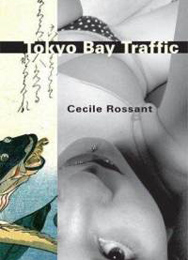

Review: TOKYO BAY TRAFFIC by Cecile Rossant

Review by MIKE WALONEN

Cecile Rossant’s Tokyo Bay Traffic (Red Hen Press, 2008) shifts kaleidoscopically in narrative focus, providing a panoramic view of a surreal, hyperreal Tokyo defined by sex, technology, and simulation. Three principal characters emerge from the alternating prose narration, dreamlike impressionistic sketches, dance choreography, and free verse poems that collectively make up the text of the novel: Kang, a bright accountant burned out with office work and his lack of opportunities to climb the proverbial corporate ladder; Livia, a dancer, the daughter of a domineering Okinawan mother and absent American GI father; and Ki-ku-ko, who goes by the name Ja-ki-O (get it?) at the sex club where she works as a “girl-girl” until, upon losing an eye, she goes into business on her own, copulating in a manner that merges and transmutes bodies and physical environments in a manner somewhat reminiscent of J.G. Ballard’s Atrocity Exhibition. There isn’t much of a story tying these characters together: their identities are established, they explore their environments, and they encounter each other and screw in poetically abstract detail that is much more cerebral than titillating.

However, the imagery in Tokyo Bay Traffic is quite vivid and symbolically rich. Rossant’s novel starts off with a juxtaposition of images of an advertisement for a sex club featuring three women’s derrieres, a butcher’s advertisement showing a diagram of different cuts of meat, and a group of furtive, dirty men drinking cheap sake on the street, the sight of whom is described as off-putting, “like seeing an opened package of sausages left out on the street to rot in the hot sun.” This series evocatively presents one of the main thematic clusters of the novel—the objectification of women through fragmentation into disparate sexually charged parts by a male desire that is represented as surreptitious and often seamy. Throughout the work this theme of fetishized segmentation is pursued with quasi-obsessive frequency, as sex club patrons are mesmerized by bare breasts, a club worker sells her leg to a man, and, in the lurid and haunting “Refuse All: Pink Rubber” chapter, a man serially over-inflates blow-up dolls, causing them to explode. Here the unbearable pressure of the excited male libido is shown to cause women to come apart; that is, not only are women fragmented by being psychically reduced to an agglomeration of unevenly valued body parts, they are also fragmented, bereft of their cohesiveness of subjectivity, by the overwhelming pressure they face as objects of desire. Attempts to put these women back together—the leg purchaser’s efforts to connect it to another leg and Kang’s attempt to piece the blow-up doll fragments back together—prove ultimately futile.

Another central theme of Tokyo Bay Traffic is the alluring but ultimately vapid nature of the superficial play of signifiers that constitutes much of our postmodern phenomenological environments. Fashion is one aspect of this, with its marshalling of visually stimulating surfaces to variously augment, conceal, and highlight parts of the body. The novel’s setting, its fictional rendering of lived conditions, is another. The Tokyo the characters of the novel inhabit is, in the parlance of Jean Baudrillard and Umberto Eco, hyperreal, a morass of mass mediated images so repeated and so densely saturated that the ultimate nature of the real is an irrevocably lost quantity. It is not only in the sex clubs of Tokyo Bay Traffic that the image forever takes the place of a bygone underlying material reality, but in the streets as well, particularly in the proxy New York “theme park” (for lack of a better term) lying across Tokyo Bay, Fresh Style New York. Much like Julian Barnes’s condensed, mock England in England, England, but without the humor, Fresh Style New York presents a reconstituted Big Apple based on an idealized view of what New York, and synecdochically America, is all about. The lack of substance of this vision, its permeability, is strikingly illustrated in a scene in which Kang finds a row of skyscrapers to be only projections upon a large screen, which he pierces through, finding only a shallow pool of water behind.

Rossant’s novel is executed in the spirit of works, like Steve Erickson’s The Sea Came in at Midnight (1999), that attempt to explore Japan as postmodernism “ground zero,” the place where the cultural trends that can be collectively described as postmodern have found their most salient and unfettered manifestation. As such, it is open to the same critique that has been levied at Roland Barthes’s Empire of the Signs: that it uses Japan as a vehicle to explore the theories of the author at the expense of representing Japan in its own historically determined cultural topographical terms. Along these same lines, in representing Japanese women in stock terms of Oriental feminine submissiveness (particularly psycho-sexually), Tokyo Bay Traffic dangerously flirts with the Orientalist representational mode, in all of its caricature and disempowerment.

All told, Tokyo Bay Traffic is often conceptually captivating, and is adventurous in its textual experiments – such as its long sections of dance instructions couched in imperative terms. Its characterization is fairly flat, but then the novelistic convention that psychology is a matter of a coherent self lying behind the facade of our bodies and actions is a large part of the narrative tradition that Tokyo Bay Traffic and works of its ilk repudiate. It makes for an amusing, intellectually engaging read for those not married as readers to conventional realist narration.