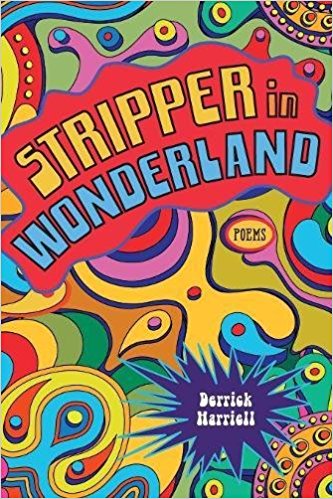

Review: STRIPPER IN WONDERLAND by Derrick Harriell

Review by DIAMOND FORDE

While Derrick Harriell describes his third collection of poems, Stripper in Wonderland, as his most autobiographical work yet, the book’s greatest success is its myth-making. Southern spaces Atlanta and Mississippi play backdrop to any number of strange phenomena. Gaia stomps. Ghosts haunt. UFOs hover over the projects. While these phenomena certainly have their thumbs on the pulse of Stripper in Wonderland’s heart, it’s Harriell’s mythologizing of the mundane inhabitants of these spaces—the strippers, the good ol’ boys, the fathers—that aggrandizes this collection to pure epic. Emboldened with music and myth, Harriell’s poems sing. In this collection, the ghetto plays the hero; its charms and harms ready for tragedy or ascension. But the most significant theme of Stripper in Wonderland is the mythologizing of the father.

In this book, the father forms a triumvirate. As one might expect from a collection called Stripper in Wonderland, it tightropes the stripper/daddy trope, especially in poems like “Bands.” But more surprising are the portrayals of Pop—the speaker’s father—and the images of the speaker entering his own call of fatherhood. As the reader carries through the collection’s three sections, the mythology of the father transforms.

As could be expected from the eponymously named first section, this chapter introduces the collection’s many mythological elements. These poems are “skunk cum” and “blooming Ruger.” At the same time, the poems are delicate enough to hold the fraying thread between father and son. In “Pop Found the Apocalypse at the Bottom of a Bourbon,” Harriell proves that a well-placed couplet can capture the awe between son and father:

notes in our funky ghetto blue who knew

greys abducted the ghetto too you knew

The space between the lines in this poem recreates splintered thought. In some places, phrases are fragmented until language nearly falls apart: “you flickered your tiny cop // flash / light the dope fiend sky”. In this example, even the tiny bonds between compound words collapse. The presence of fragmentation in the beginning pages of Stripper in Wonderland forces the reader to ask, where does the fragmentation begin?

Perhaps in death.

So many ghosts haunt these arcs. For example, in the poem “Rapping with Ghosts,” the speaker talks to a “translucent projection”. Still, it is what the speaker and the ghost do not discuss that haunts the poem:

I don’t mention what he did

to you / don’t mention the gun in my lap

for days / I would find him / I would kill him

“Rapping with Ghosts” surprises readers with two ghostly entities—the translucent projection of a loss loved one and the ghost of desired revenge.

The dead are so frequent in Stripper in Wonderland that it’s hard not to imagine this text as an underworld. Take the poem “Make It Rain,” where the dead walk in and out of the speaker’s imagination. The poem asks, “what happens // when daddy shows // in your dreams / or closet”?

Still, these ghosts make room for the development of the father triumvirate. While the second section focuses on the ghosts of Mississippi living, the Pop figure of the first section becomes a ghost himself. The second section of the book, “Astronauts in Mississippi” brings Pop and his ghost to Mississippi ground. The speaker in “Baptist Memorial” begs, “Dear Father / Hail Mary // Stay With Me”.

The second section undertakes another crucial step—bringing the collection’s most prevalent speaker to fatherhood. Here the speaker becomes father to a baby on the cusp of dying. Take these two beginning lines from “The Cowardly Obstetrician Delivers a Body”:

and he’s not breathing / not breathing

and blue / not breathing blue baby of mine / no

We close “The Cowardly Obstetrician” unsure if the baby is alive. We remain unsure until “Namesake,” the last poem of the second section. Here a ghost appears by the bassinet, and readers are uncertain who the ghost is. Harriell continues this uncertainty until the last four lines of the poem.

What’s so important about the ghost in “Namesake” is how divorced it is of any expectation of time: “I studied the outer space of his bassinet / for months for planets for comets for you”. Ghosts like this create a conflict of time that becomes the foreground in “Pimping Through Eternity,” the book’s final section. While possibly the most chaotic section in Harriell’s Stripper in Wonderland in terms of content, poems like “Fogging the Time Machine Windows” return us to the careful craft and language from Harriell’s first section. By the time Harriell’s book ends in “Ascension,” we are so lifted and luminous, how can we not be the ghosts haunting these poems all along?

Because I would be remiss without turning to the collection’s final ghost—the reader. In a DM Online interview, Harriell described this book as his most autobiographical, and it shows. As readers, we are swept up into this collection of supernatural memories. We float in and out of the speakers’ consciousness. By the end of Stripper in Wonderland, we, too, are ascending, elated by the new-formed bond with the collections’ speaker. These poems are a fantastic celebration of connections—between reader and poet, language and music, father and son.