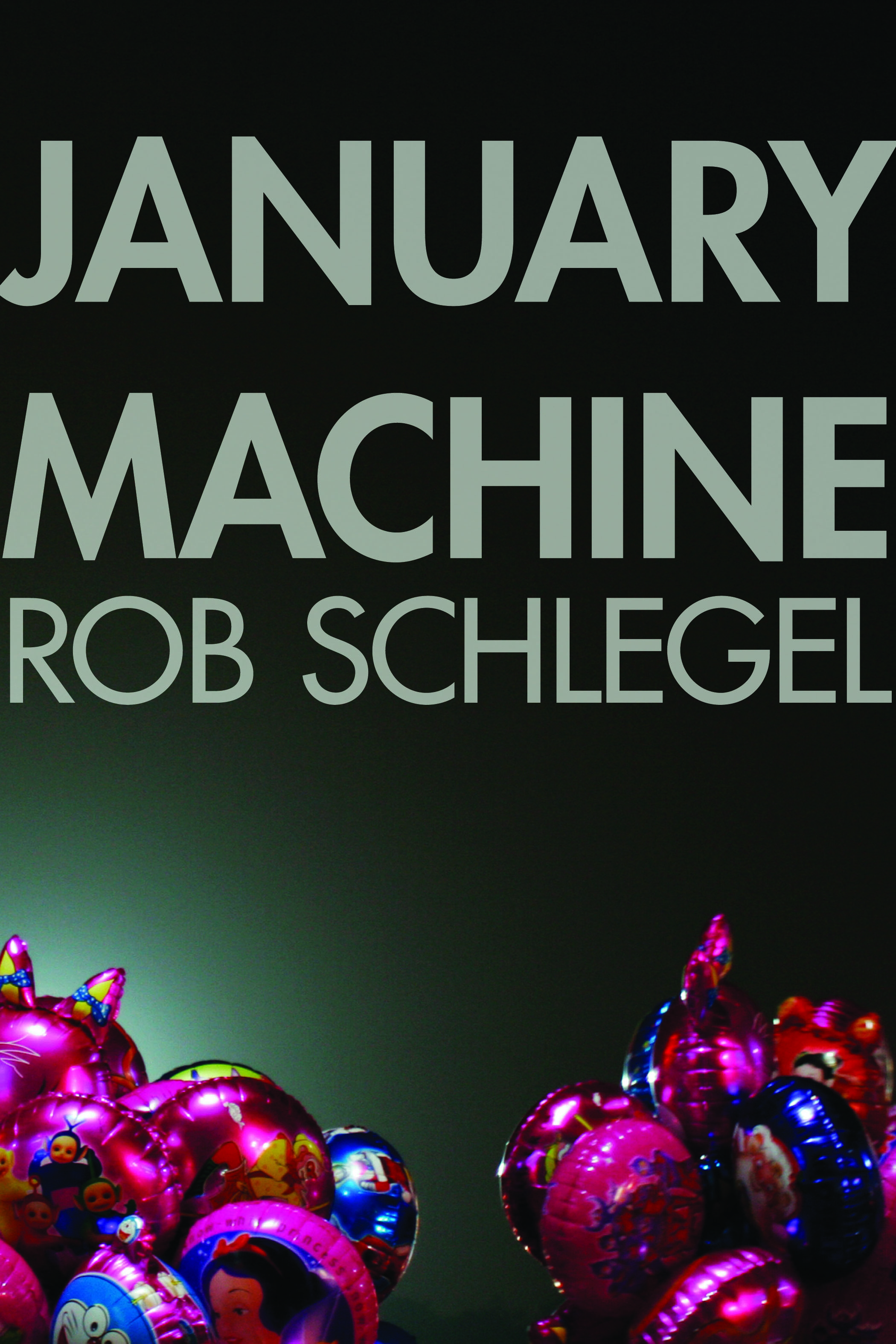

Review: JANUARY MACHINE by Rob Schlegel

Review by LAURA KOCHMAN

Rob Schlegel’s second book, January Machine, takes the form of a book-length poem, using the page as a unit of measure. Along with form, January Machine centers on its speaker, the question of the speaker-self and its role within the nation-self. With this speaker, we explore a landscape that shifts from foot to foot, poem to poem, a landscape simultaneously political and capitalist and gendered and endangered and nationalist and not. The entity called America is the landscape of this book. Schlegel’s speaker enacts American self-conflict, identifying as

Medium-sized American eyes.

Medium-sized American attention.

I am an American television

pipe bomb. Medium-sized

American fear. I am an American

television commercial. I exhibit

unusual. I am an American

unusual behavior. I exhibit

an overture, local—to what—to use

and useful.

In these ten lines, we see “eyes,” “attention,” “television,” “fear,” “commercial,” “exhibit,” and “behavior”—a pathology of American experience. The speaker’s “I” gets repeated five times, drawing our attention to the rhyming “eyes” that take in the landscape (the speaker’s eyes) and that stare back at the speaker (the eyes of the body politic). The speaker thinks often about eyes and looking, the acts of both watching and being watched, which add to the anxiety that speaks in most of these poems. Even the birds in January Machine “are looking for places to glimpse / their own reflection so that when // they despair they might feel witnessed.”

There are a few individually named characters, recurring and not, but they are filtered through the speaker’s attention, part of the American kaleidoscope. To name a person seems significant on the same level as naming a month of the year—significant only in the act of forming a shape against the landscape. Schlegel calls attention to the word “I,” often starting a section with a description of the speaker, but in declarations like “Here I am sipping 36 ounces of Coke / from tiny plastic straws” the speaker only folds back into the capitalist American landscape. What speaks at the heart of this book is the fear of getting swallowed by the crowd. He admits, “I live in fear till fear becomes / that part of me / impossible to face,” forced to turn away from his own reflection, to lack a witness.

At the beginning of January Machine, Schlegel gives the reader six separate epigraphs, titled “Bellwethers,” six pieces of text that will create or influence the trends of the book-length poem. What they have in common is their sense of an unnamable trauma, a difficulty in definition. We begin here, on the unstable footing of six different voices, and that sense of instability and violence continues through the text. Reading January Machine is overwhelming and emotional, cresting through the even rhythm of Schlegel’s three- and four-line stanzas before diving down into formal interruptions like the titled “Static” sections. I got lost in the rhythm, my selfhood dissolving and becoming another reflective if fractured material in the landscape.

Halfway through the book, the speaker reaches a moment of emotional climax and surrender. The section begins “Theaters of mollusk surrender props,” a different sort of opening and language than we’d seen earlier in the text, a caution that things are about to upend. Here, the speaker gets careless with language and lengthiness, leaning into the chaos that he’s been observing all along. He effectively throws up his hands. Oddly enough, though this section feels the most reckless, it’s also Schlegel’s most straightforward portrayal of how it feels to witness the American political system:

I can hear the sea narrating rumors

from middle America

where the high grass does not mark

the edge of the beach, nor the shorebird’s

absence returned as stress between

genders in the losing half of

April when fear is a venue in states,

in cities beneath silent skies crazed

with clouds manmade by men

who resemble me listening for snow,

representing Plan B to find three

heads talking past each other

in the January machine

The speaker is simultaneously separate from this scene, hearing rumors from afar, and implicated in it (“clouds manmade by men / who resemble me”). Fear is a literal location. This is where the title of the book is drawn, and where it becomes most clear that the machine is many things: the nation, the self, the author, the text. It hums with a sense of January, which is a beginning and a definition, the endlessly repeating calendar restart. Scary, right?

The speaker is helpless in the midst of everything, and following this crescendo of helplessness, we get static. All the noise of the landscape condenses into individually-titled “Static” sections, focusing on a single image or idea. They are short, becalmed. The remainder of the book alternates between untitled sections and Sta

tic sections, perhaps having found a way to structure the self, to be silent inside the noise of the overbearing country: “I feel a near // Paralyzing anxiety to speak.” The shift in structure brings me back to thinking about the movement and prediction of trends, the bellwethers looming at the beginning of the text like oil wells, pumping that unnamable trauma in the distance.