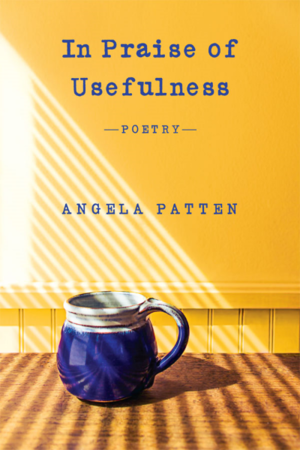

Review: IN PRAISE OF USEFULNESS by Angela Patten

Review by THEODORA ZIOLKOWSKI

In Praise of Usefulness, Angela Patten’s third collection of poetry, meditates on the boundaries between childhood and adulthood and Ireland and America. The recurring images and motifs of boundaries and maps are in constant conversation, giving us an occasion to reconsider the terrestrial, interior, and language-driven borders that have the power to both confine and free us. Through a blend of candor, warmth, and humor, the music of the voices that animates these poems reflects the collection’s seamless attention to the flexibility of language.

Patten’s poems are in pursuit of elevating our daily lives. In the collection’s title poem, the speaker begins by rendering the beauty of objects from their making — “the long spoon hammered / from a single hunk of metal;” “the bowl my neighbor culled /….from common clay;” “the four-pronged / metal fork my father fashioned / to protect our hands and faces / when we toasted bread / at the open fire for tea (1-2; 8-11; 12-16). Handcrafted objects are imbued with beauty because they carry the nature of their bearers with them. It is ritual that elevates these objects beyond their material charm.

Accordingly, the pursuit of and attraction to ritual in daily life is a source ripe with promise. Later in the poem, the speaker describes her mother’s adoration for “the utility of kitchen gadgets,” yet how “she underestimated / usefulness as if it was only / beauty’s poor relation” (17; 24-26). The speaker proposes instead “this cup that holds my sacramental / morning coffee” (33-34). Objects are thus, by the sheer dependability of their performance, containers for transcendence — from their merely physical common uses to the divine.

The opening poem in In Praise of Usefulness, “Tabula Rasa,” weaves the threads of an origin story. Through a retrospective glimpse of her introduction to Roman Catholicism, the speaker describes the church where she was christened.

That was a somber place, full of statues

of the crucified Christ

laid out in his mother’s arms

like a broken mirror.

I was given martyred saints

for nursery mates, medals

and holy pictures for protection

blood and thorns for my dreams.

(41-48)

Here, as throughout the many exquisitely wrought poems that compose In Praise of Usefulness, Patten’s voice rings like a bell.

Many of the poems chart the poet’s Irish roots and her negotiation of adulthood as a writer living in America. A vividly rendered portrait of Roman Catholicism often serves as a backdrop. In Praise of Usefulness also catalogues a series of mirrors between the past and present selves. In “Mea Culpa,” for instance, the tendency to apologize for anything and everything, a trait the speaker attributes to the Irish, is reflected in the poem’s closing lines: “Say you’re sorry, we tell our children / when we catch them acting the maggot. / Or I’ll give you something to be sorry about” (23-25).

Sometimes, Patten’s speaker adopts the voices of her Irish parentage, or embodies the vocabulary and modulation of one of these voices just at the edge of the poem’s close. In “Making Tea for My Father,” the speaker provides specific tea-making instructions with a cadence that spills into the cautionary note in the poem’s final couplet: “Now that will put the red neck on you / and a bit of hair on your chest and no mistake” (20-21). In “Things Your Mother Told You,” the concluding stanzas reciprocate a gratitude the mother of the poem is in constant pursuit of:

Suddenly you saw her as she had always been —

her generous soul and fine intelligence

under all the talking. And of course

it was too late, you were already gone

and she was still saying goodbye.

But you imagined how she would have blossomed

had they ever let her make her own decisions

had she been lucky enough to have had your life

(41-48)

In “Thanks for the Genes,” the speaker uncovers another kind of mirroring. She likens her physical attributes to her father, praising him for her own “slender body, its quick metabolism / its uncanny knack for fighting off infection” (2-3). Here, the human body is a representation of the relationship between what it means to embody the traits of the ones you love and to recall the ancestral histories that make you.

Patten’s poems buoy between past and present memories; they enact occasions for solitude, offer genially rendered notes of caution, and leave us lingering with the warmth of the speaker’s good will. It is the sound of these poems, the rhythm of speech from generations past — fueled by the rise and dip of their cadence — that make it seem only natural to feel, by the collection’s end, that we have been submerged into memory’s most explicitly rich terrain.