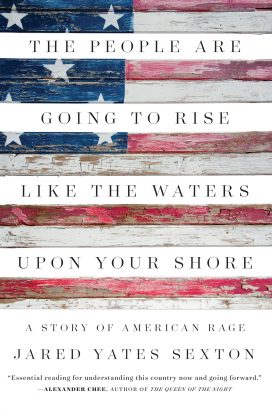

Review: THE PEOPLE ARE GOING TO RISE LIKE THE WATERS UPON YOUR SHORE: A STORY OF AMERICAN RAGE by Jared Yates Sexton

The People Are Going To Rise Like the Waters Upon Your Shore: A Story of American Rage

Jared Yates Sexton

2017

320 pages

Review by CONNOR TOWNE O’NEILL

On June 14, 2016, Jared Yates Sexton drove the five hours from his home in southeast Georgia to attend a Donald Trump rally at the Greensboro Coliseum in North Carolina. Trump had recently become the presumptive Republican nominee, the crowd was stirred, and Sexton, uncredentialed, live-tweeted the event from among the faithful. Here’s a partial, but revealing, list of things Sexton heard from the crowd, broken down by topic.

On the recent shooting at Orlando’s Pulse nightclub: “The gays had it coming.”

On Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton: “a bitch.”

On journalists: “kill them all.”

On immigrants (this one a parent to their child): “Immigrants aren’t people, honey.”

By the time he reached his car that evening, Sexton’s reporting was trending nationally.

The crowd in Greensboro was “simmering with anger and pent-up rage,” sentiments that Sexton explores at length in his new book about the 2016 presidential campaign The People Are Going to Rise Like the Waters Upon Your Shore: A Story of American Rage (Counterpoint). A fiction writer by trade, Sexton had been covering the campaigns for over a year by that point for the Atticus Review, an online literary journal. Sexton’s reporting from the scrum brought Twitter followers by the thousands, commissions from The New Republic and the New York Times, and death threats from the alt-right (apparently the new sign you’ve made it in American political writing). Explaining his new role as a political correspondent, Yates cites novel procrastination and a desire “to get back in the thick of it.” But just what exactly “it” was didn’t reveal itself in full until that day in Greensboro in June.

The People Are Going to Rise is a comprehensive chronicle of the 2016 campaign from the margins. Sexton reports from the cheap seats (and the barstools), and the book is composed of the many and often bracing things to which Sexton bore witness: the under-the-breath (and not-so-under-the-breath) mutterings at rallys, the off-site seig heils at the Republican convention, the elbow drops to car windshields at the inauguration.

And Sexton makes the lack of access a feature, not a flaw, of the book. His theory of the case of Trump’s victory is that “Trump wasn’t the cause; he was the disease personified,” a yammering id following the “zeitgeist of the White and Angry.” So where better to be than general admission? The story was out here all along. And this is what makes Sexton’s reporting such a revelation. Sexton writes that “before [he] went into the crowds and reported, there was very little in the way of eyewitness accounts as to just what was brewing among Trump supporters.” The press in Greensboro, Sexton explains, was cordoned off from the crowd, and journalists “tapped out their reports on laptops while, a few feet away, supporters in the scrum by the stage were busy venting their anger and spewing racist and misogynist slurs.”

The Greensboro rally is just one of many whistle-stops covered in the book. The first section toggles between the two parties’ primary battles, tracking discontent across the political divide. (The book’s title comes from a cardboard sign abandoned by a “Bernie-or-Bust” protester at the Democratic convention.) And while the reporting feels tentative at first — early chapters are framed by a quick bit of scene-setting at a town hall, colored in with broad-strokes summary before ending back in scene — Sexton has the observational chops to keep things lively. In one memorable moment, he describes Bernie Sanders as “a wild-haired prophet come to deliver unglad tidings” who grips the lectern “like it might leave him.” On Trump’s manner of answering debate questions, he writes: “He happily manipulated every single question into a piece of fleshy red meat for his base and marbled it with extra fat.”

The fly-on-the-wall approach does leave the book feeling depopulated at times. Sexton reminds us time and again that he hails from a blue collar Hoosier family, but they are never heard from. The book might have found even more texture and intimacy had Sexton let us hear more from them. Instead, their grievances, fears, and desires — along with their individual voices — are set aside in favor of Sexton’s broader observations of the election of our discontent. The same holds true for his reporting on the right and the left.

But when Sexton sets off on a road trip with Dave, a young Republican in a polo shirt “the National Guard couldn’t untuck” to attend a Clinton rally in Ohio, the book hits a deeper register. The buddy-comedy approach might feel like a schtick except that it’s a welcome change of pace to spend some extended time getting to know a character. As they schlep up and down I-75, disagreeing about everything from peanut butter to the role of the federal government in ending Jim Crow-era segregation, Sexton is able to convey a more textured sense of how we come to our beliefs and how we come to be cordoned off from those with whom we disagree. It’s a welcome counterweight to the anonymity of his usual reporting style. To be fair, Sexton is not trying to model a way of dialoguing across our political divide. If, as he writes, the bitterness felt among lower-class white people in flyover states is a cancer that can quickly metastasize into the racial resentment of bottom-rung avoidance, Sexton sees his role as more public health researcher than attending oncologist.

Sexton is more cogent when offering a media critique that he threads through the book, laying out a right-wing moebius strip of audience, message, and medium. Trump is simultaneously the extension of his base but also “the walking, talking embodiment of the cable news show” he loves so well. In Sexton’s view, the reality TV president rides a feedback loop with as much static as signal — infotainment imitating life imitating infotainment, all of it slouching toward the oval office. This formulation, coupled with a scathing post-mortem (or, as he terms it, an anatomy of a car crash) of the Clinton campaign, functions as an interconnected, incisive ending to the book — as depressing as it is enlightening.

Even with the fresh-hell fatigue of following the resulting administration, and with that campaign still in recent memory, revisiting it with Sexton lets you see the horror anew, with a deeper sense of its consequences. And as the water level rises higher on the shore, Sexton continues to be a dutiful correspondent. He recently exposed the anti-Semitic history of the Twitter account whose doctored Wrestlemania GIF President Trump retweeted amidst his feud with CNN. Just writing that sentence requires Dramamine, but Sexton’s work remains ballast in the pitch and yaw.