Review: IF THE TABLOIDS ARE TRUE WHAT ARE YOU? by Matthea Harvey

Review by BETHANY STARTIN

“When I say we I mean/me in a wide wide dress,” Matthea Harvey writes in “On Intimacy,” her words illustrated by a silhouette of a woman clothed in a Georgian-era ball gown. Throughout If the Tabloids Are True What Are You? (Harvey’s fifth poetry collection) we are cast as voyeurs to the museum of weird concealed beneath that dress, each artifact kept at a distance with the mercurial nature of Harvey’s writing, which moves quickly and capriciously between the objects on display.

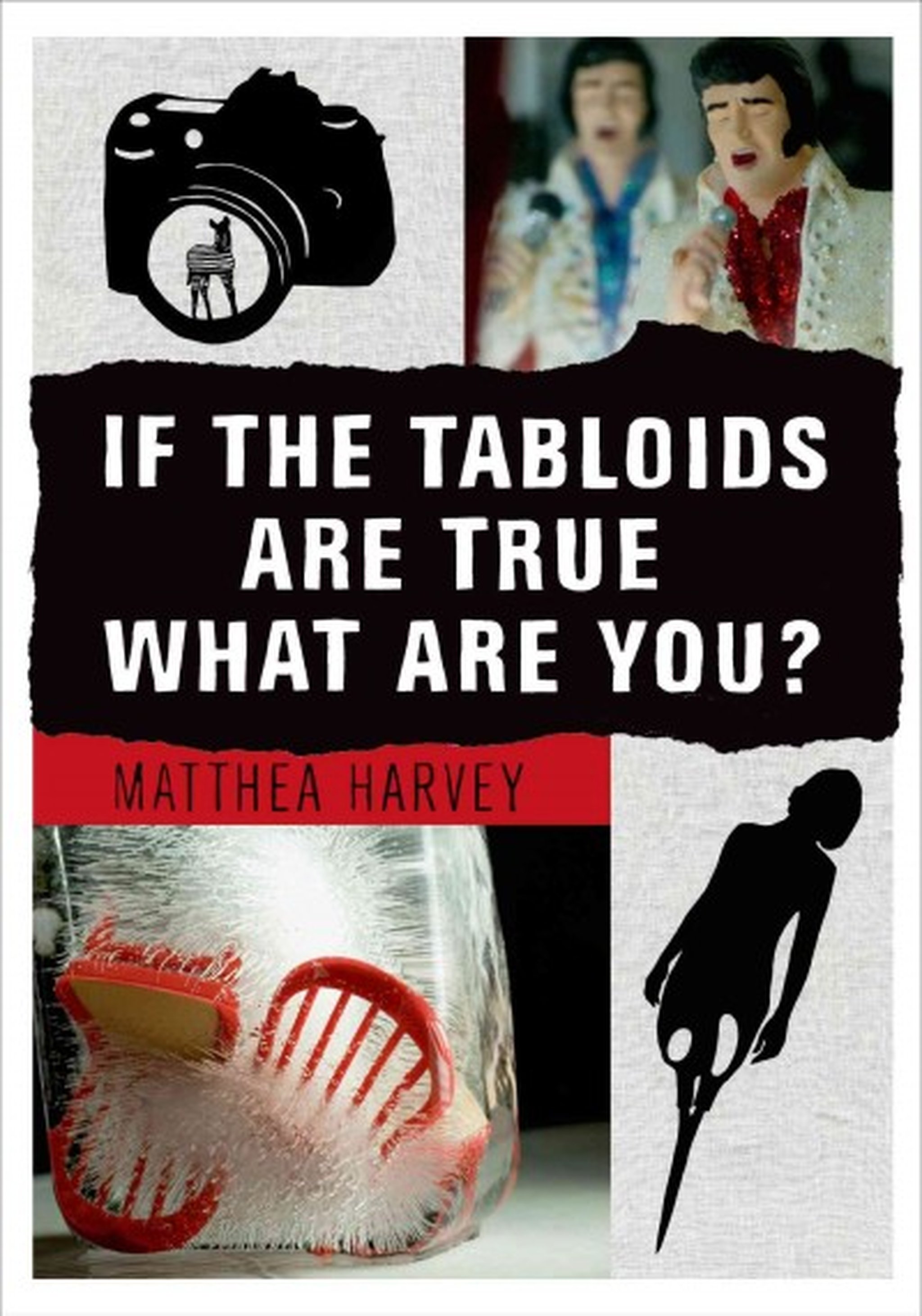

And there is a wealth of them. Harvey opens with a series of prose poems centering on the mundane problems of mermaids, one tired by the predictability of modern life, another feeling objectified due to her job as a model, a third fixated on maggots and dead things to the exclusion of the living. Later in the collection, she treats us to a starkly lovely erasure of Ray Bradbury’s “R is for Rocket,” and offers a glimpse of what modern-day constellations might be said to resemble. (The “No More Suicide Fox” constellation is particularly charming). Harvey’s original art couples well with her poems. Her artwork matches the richness of her lines and moves from silhouette cutouts of mermaids — sporting common house tools in place of their tails — to photographs of ice cubes with dolls and chairs frozen at their center, and finally even to sewn images of prototype telephones. Most of these, like the silhouettes mentioned above, serve only to deepen the engagement with the poetry; it is difficult to look at a mermaid sporting a pistol for a tail and not be drawn into morbid thoughts. But occasionally, I found myself less enthralled – as with the images for ‘INSIDE THE GLASS FACTORY,’ which all depict a variety of colored glass bottles. For a poem that does so much work within the collection, I wanted to see more of that work reflected in the accompanying artwork.

Both poems and artwork knowingly flirt with kitsch. There are photos of brightly-colored plastic toy televisions interrupting poetry about cloning your very own mini-Elvis: “My friend, who’s strangely loyal/to the Original Elvis timeline, maintains hers/nicely, smoothes baby oil onto his black hair.” There is no apparent desire here to have us look too closely at what is on offer; the kitschiness solicits smiles rather than deep contemplation. And while I often reread and pondered certain poems in the collection, for the most part I found myself enjoying the sensation of pure voyeurism, of having the images wash over me without requesting constant feedback.

Elsewhere in the book, Harvey offers us a longer narrative poem titled “Inside the Glass Factory.” In the poem, a group of flesh-and-blood girls trapped in a lifeless glass building, constantly watching the outside world and yet unable to touch it, create a ‘girl made out of glass’ as an attempt at articulating the natural images that they see. Three pages into the poem, Harvey describes the yearning desire of these girls to make their glass creation as real as possible:

Not one finger here has ever felt fur,

seen veins or bones except under

the cover of skin, but they bypass

all that with the force of their dreaming—

how best to make her glass hair seem to

stream down her back, whose forefinger

they should choose to dent in her dimples.

The fierce and finely-wrought desires of these girls is one of the absolute highlights of the collection, and emphasizes the sense of entrapment her speakers suffer. In the voices of the girls, we discover the shared desire for escape:“They used to/run their fingers along the walls,/searching for a way out, but that only/smeared the sky.” The struggle for escape, both interior and exterior, returns again when Harvey gives us a Michelin Man possessed by Shakespeare, declaiming that “It’s very hard to breathe.” This sense of claustrophobia is only enhanced by the photos of dolls trapped in ice and images trapped on TV screens. The tension that stems from this desire for escape keeps us taut and expectant, waiting for the wistful figures in these poems to break out of the lines that constrain them.

There is a preoccupation with invention throughout If the Tabloids Are True What Are You?, and particularly with reinvention. “There’s a String Attached to Everything” tells the story of a “puppet snob” who “remembers gluing pebbles to the hooves of her horse marionette so it could properly clomp across the stage.” Later, in “One Way,” we see the impact of the arrow on a society that had never before conceived of them: “Arrows led to purchases./Arrows led to adieus. A simple shape/had turned us all from cars into ambulances,/keening with intent.” Harvey manipulates these inventions beautifully, like a puppeteer who succeeds so well that we don’t even look for the strings. All of these inventions feed into the greater artifice of the book, creating for the reader a sense of perpetual movement and innovation.

Most notably, though, this preoccupation with invention appears in the chapbook “Telettrofono,” which concludes the collection. The chapbook, a play in half verse, half prose, is based around the life of Antonio Meucci, the inventor of the precursor to the telephone — later eclipsed by Alexander Graham Bell, and bankrupted by debtors — and that of his wife Esterre, a costume designer. Narrated in various ‘modes’ (the ‘Verifiable Fact Mode’, ‘Fairy Tale Mode’, and so on) the chapbook almost runs the risk of feeling exhausting. What prevents this exhaustion is the conceit of Esterre as not human, but mermaid, narrating sections of the chapbook via—of course—the ‘Mermaid Monologue Mode’:

Humans, do you not all breathe the same

air? Yet you curtsey to that one, kick

the other. Some feet are slippered in pink satin

and carried over puddles, others bare.

When we arrived, they gave us a man to serve us,

as if he were a pebble. The theater is full of

invisible rules. White ladies may eat ice cream

on the right side of the patio.

This conceit is a delicious one, especially mirrored as it is in the other modes of narrative present. The mermaid chorus in the ‘Marine Telephone Mode’ takes the mermaid’s conceit and reflects it back at Esterre, with lines like, “Humans are lucky to make it to/eighty and then with awful turtle-wrinkles.”

In this last invention, Harvey’s collection comes full circle. The mermaids who open the book are landlocked and worse off for it, their tails no longer tails and their problems entirely mundane (the Backyard Mermaid, for one, has an ongoing rivalry with the family cat). Esterre’s mermaid is at first landlocked like the others, but when the curtains close, she returns to her natural habitat. So too do the girls in the glass factory, having explored the outdoors and decided it wasn’t for them: they return to their factory, ‘sliding barefoot/between kiln, conveyor belt, workshop.’ When the collection is over, Harvey’s inventions revert almost without exception to their picture-framed (or TV-mounted) surroundings, unable to fully breathe.

After “Telettrofono” ends, one remembers the earlier pages of the book, where the silhouetted figures still remain on the verge of motion, holding their potential within their stark, unreal frames. Although these initial poems work best in capturing the artificial dramas of Harvey’s created landscapes, “Telettrofono” offers its own charms, weaving the real and the impossible through the lens of its half-forgotten inventor protagonist. As Harvey herself puts it in an interview, “Poems are impractical telephones, prone to mishearing, distortion, but perhaps indirectly a means to the truth.” In the distortions on offer here, through the many modes of speaking that Harvey variously inhabits, there is much to return to over and over, an accumulation of tiny and fascinating truths.