Review: POP CORPSE! by Lena Glenum

Review by LAURENCE ROSS

Lara Glenum’s book, we are told, is a “vocal prosthesis.” Pop Corpse is written in a voice that is unabashedly a stand-in for something else, a substitute for something more natural to which we—and the narrative voices—do not have direct access. The voice(s) we receive are not natural; they are hampered with artifice, though delightfully so. Just as every open casket requires a make-up artist, there is nothing natural about this way of viewing, a body (of work) on display. The make-up/make-believe artist makes up/covers up the fact that the body is in a continual state of decay. Pop Corpse asks us to envision, to believe, in a land far far away in which we are told: “There is no land.” This book asks us not to exist in a “willing suspension of disbelief” but instead asks us, like many fairy stories, to believe in the artifice[i]—at least until we close the cover.

The world of Pop Corpse opens with a scene that is post-Disaster: yes, “floating islands of plastic garbage.” “There is no land,” nothing natural left—anything we see or hear or touch is mimetic of nature/our nature, each blurted confession like a hair extension: admittedly stylized but desperately holding on to some semblance of natural physicality. And this semblance/resemblance of natural physicality is what the characters of Pop Corpse seem to desire the most.

Pop Corpse, in many ways, places the reader in the realm of theater. We are reading a script scribbled with scenes: the Goo-Goo Lagoon, The Yumfactory, The Royal Disorder Panic Party, The Isle of Noise. Suffering is as common to the landscape of the text as a blackhead on the surface of a teenage nose, or a Tiffany’s charm around a teenage neck. “My suffering has become frivolous & ornamental”, says a narrator. Suffering, though common, is seen as separate from the self—an ornament to wear, a thing of implied grandeur. One character chants: “But we’re outrageously mod! We spiritualize consumption! We’re nothing but surface!” These characters revel in their pearled acedia yet are ravenous for fleshy façades. Their consumption is consumptive, like snakes looped into zeros and half-heartedly eating themselves bit-by-bit, bite-by-bite to nothing. “It is all so festively boring,” says the text, and yet we watch the characters “Cannibalizing themselves in2 art.”

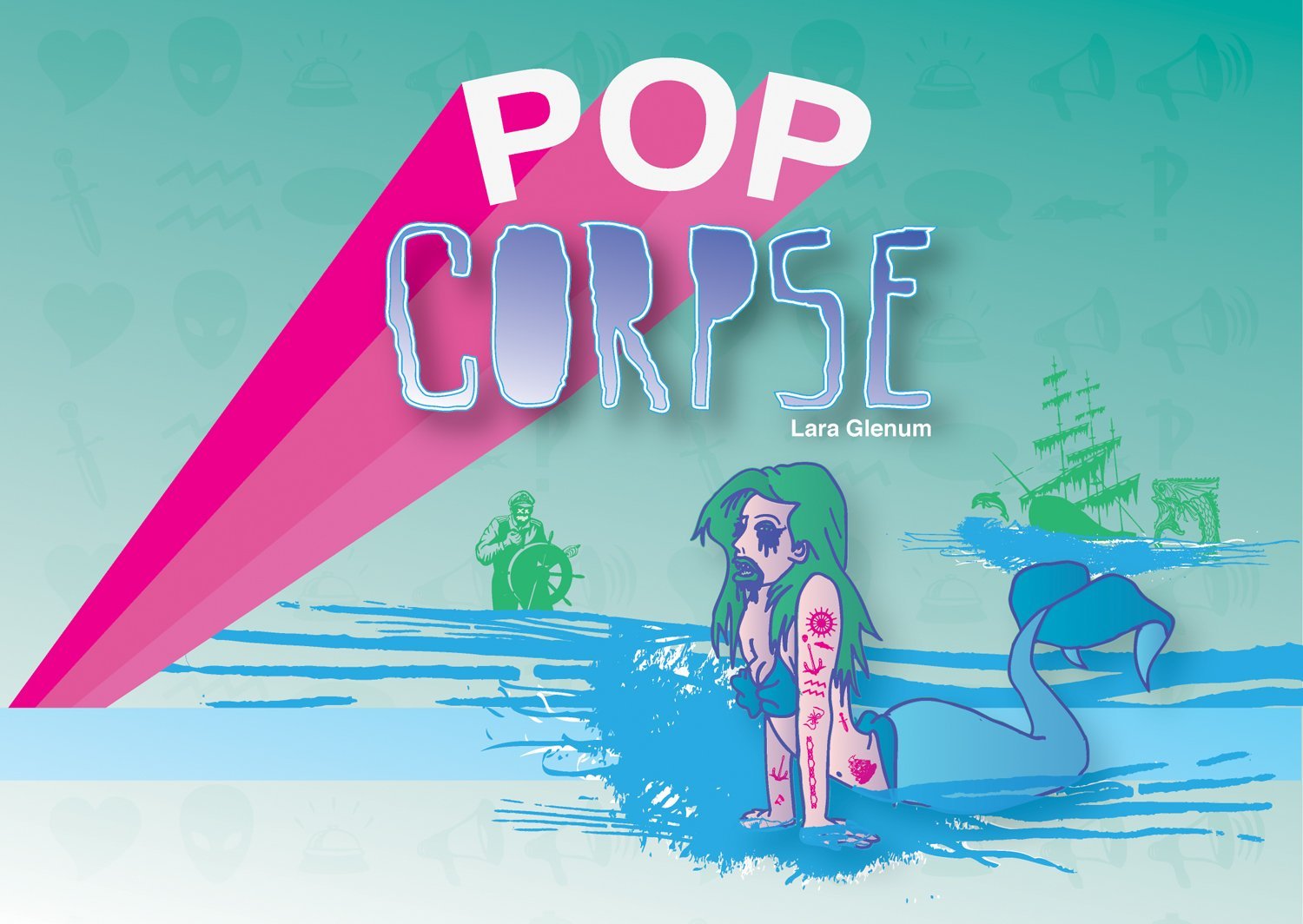

Horny mermaids that populate the text have hormones firing as fast as fingertips on a cellphone. What we read/see/hear is the voice of impatience and sexual frustration: “2 spectacles of ornament and excrement.” The voice is also one of mixed metaphor where there seems to be no viable alternative. (“The ha ha albino sky / rotting like meat in my throat”.) The hybrid image, like the mermaids themselves, is the (un)reality and the reader is left to make sense of it or not. To ask, as the text does: “Is this some avant-turd jank off”?

With lines like “Ensorcel yrself / 4-evah / in loaves of hottie blubber” we are immersed—whether we asked for it or not—in the “candied decay” of cultural rot. (Though I would posit, as the text does, that this rot is simultaneously a type of rapture: if this is the end of the world as we know it, people are clamoring for a front row seat and trying not to drop their 3D glasses along the way.) Pop Corpse seems in direct dialogue with Harmony Korine’s recent film Spring Breakers—each work a sensory bingeing—and I almost expect to see James Franco, right around the corner, in dreadlocks and a grill, Alien but still a recognizable figure.

When we read the title of what I will call a “chapter” (“LITTLE MERDE-MAID & HER SHITSTAIN OF A STORY”), we can wonder who it is that is speaking in this abrasive voice. This voice is a patina of teenage shock-value, of coarse language and crude gestures, bedazzling a critique of the bind in which the teenager might find himself/herself/themselves: here is a hyper-sexualized universe that I am not properly equipped to handle. The mermaids lack the physical equipment to fill/be filled/be fulfilled with desire. The solution? A razor blade and a webcam: a sex organ-less mermaid who needs a Sea Witch or an X-acto knife to make any headway.

The mermaids of Pop Corpse have only one opening—their mouth/voice. And what we see/hear in the text may look/sound like textual/verbal vomit, but, as there is no other outlet, we are asked to understand. As readers, we are told: “Please, Air-Breather, those ain’t women. They got no holes. Not even a single shithole. They have to take shits out of their mouths. And believe me, they take atomic dumbs.”

There is no other form of release for those trapped in bodies or worlds that will not accommodate basic needs, that only foster a (self-) alienating suffering. And so we are given this book of poetry, it’s form: the clippings of a screen play, of graphic language and a language of graphics, of lineated prose, of staged directions, of dialogue passing between characters like ships in the phosphorescent night. By the end, by the time we reach The Royal Theater and its operetta presented by The Orphaned Nihilist Society, what we read seems the only plausible form for Pop Corpse’s contents: a form that is ever-malleable; a form that is plastic.

“Real? Lolz! Now that IS a retro term! … We’re post-gender, and that’s awesome. But we can’t fuck. And that sucks seahorse butt.” The voices and sex organs in Pop Corpse may be prosthetic, but in that world (and, in many ways, this one), blunt and blatant artifice is the only way in which we connect, our single-surfaced opportunity for intimacy. This book is a post-apocalyptic version of MTV’s Laguna Beach, where every pimple, blink, and brow-raise that was captured by those cameras has been turned into a hormone-addled text-quip. The sex-drive in our pop culture-cramped bodies, if bottled and capped, must eventually be secreted and Pop Corpse is that wet-dream-scape. These mermaids are the Real Housewives/Houseflies of the new world. Don’t be tardy for the party—“If I’m not cockgobbling by half past a lunar rabbit / Let the pageant begin”. Embrace the language, the culture, or be left out, alone, to rot.

[i] J. R. R. Tolkien writes with much more nuance about the suspension of disbelief and what he terms “Secondary Belief” in his essay “On Fairy-Stories.”