41.1 Feature: An Interview with Sarah Minor

Sarah Minor recently earned her MFA in nonfiction from the University of Arizona in Tucson, where she currently teaches and works as a visual artist and essayist. Her work has appeared online at Word Riot and in print at Conjunctions, and is forthcoming in South Look Review and Seneca Review.

Interview by CONNOR O’NEIL

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/161659587″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Listen to Sarah Minor read “Into the Limen” from 41.1.

Black Warrior Review: Could you talk a little bit about the inspiration for your piece “Into the Limen” featured in BWR’s issue 41.1?

Sarah Minor: I used to tell people that my work was made in protest of the standard US Letter page. Lately I think about this more seriously. It seems that a lot of modern writing expects to inhabit 8.5×11 or 6×9 inches like a model home, as if space did not affect or matter to text and never has. All kinds of writers let their language fall into preset rectangles to be inkjet printed on 20lb without any consideration—why?

For real though, essays for me mostly arise from the struggle to make sense of an obsession I can’t otherwise explain. In the case of this essay, the writing was fueled by the intense attachment/repulsion I still feel towards this weird family home and the spaces inside it.

BWR: “Into the Limen” works in several different modes—the reportorial, the lyric, the personal, the theoretical—what appeals to you about the multi-faceted approach?

SM: Nick Flynn talks about writing a book like traversing a mountain. He says that to develop a complete project, you have to find many paths to the top—you have to achieve various purchase on the material to understand it fully. This image helps me understand the work of poly-vocal writing, and how complex thinking is communicated through a number of voices and perspectives. Something happens in the combination of many modes attacking the same subject that is not possible through just one or two—which oddly…has to do with the emergent properties that this essay addresses.

To use an alternate image: If a lyric essayist is a performer keeping a number of plates spinning at once, and those plates are ideas, the job of every voice is to nudge each plate-idea once during its interlude into the essay to maintain the velocity of associative connections. When I come to the point where I’m stuck in a project, I try to pull in other voices or consider a new source to compliment or complicate my thinking. Then, I try to consider where the reader’s mind is along the arc of the logic and support it further. I also get bored with my own voice, and try to adopt others to jar out of this.

BWR: I really love the form of this piece, how, as you drift into lyrical memories, the lines themselves recede. Were there previous forms that the piece took in earlier drafts and how did you land on this one?

BWR: I really love the form of this piece, how, as you drift into lyrical memories, the lines themselves recede. Were there previous forms that the piece took in earlier drafts and how did you land on this one?

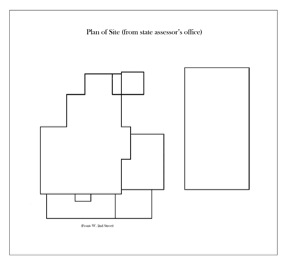

SM: Definitely—this form was hard-won from the essay it houses. At first I had the text contained in a massive blueprint of the actual house and I tried to get each section to fit into a different room. It was really a mess to read. Now I always look to the writing to announce its own structure, and to try my best to choose basic shapes. You can’t force it—or at least I can’t. So the soffit form came directly from this interview with Jim when he pointed a soffit out to me in the house. I was interested in the combination of three spaces in the soffit drawings I found later, and was also reading about emergence, and third space, so the form came together through a kind of series of bangs.

I’m trying to figure out this form-text announcement process through interviews with visual essayists on Essay Daily. Most of them are much more articulate about it than I am, but it seems to be about a particular relationship of mutual respect between each content and its form. In this essay specifically, I tried to make the thinking of each section of text fit the label of the space where it was contained in voice and structure.

BWR: This is a section of a longer work, correct? What can you tell us about the project as a whole and where “Into the Limen” fits within it?

SM: “Into the Limen” is part of a collection of visual essays united by their exploration of liminal spaces and states. This essay perhaps articulates the book’s central ideas most directly. Each piece takes on a very different form, and employs visual elements to better understand emotional and conceptual terrain in a spatial manner. Much of the writing uses concrete forms, but some essays also involve images or additional parts like fold-out pages. Every time I think the project is complete I write something else that seems to fit. I think I’m just picking at this point.

BWR: You quote Gaston Bachelard in one of the epigraphs. Are there other writers who you were reading that were helpful in working on this piece?

SM: I have a habit of going back to the same writers when I’m stuck on a project, and I remember reading both Albert Goldbarth and Anne Carson alongside Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space at that time. Research is really important for me, so I was also trying to read about squirrels and evolution and rotting wood and to get my head around emergent properties. It’s crazy what you find yourself trying to understand down a project’s rabbit hole.

I think many of us spend our time developing ideas of ourselves as unique, special creatures, so of course now that I understand myself as an artist-outlier from a family of scientists, I find most of my ideas from reading science and natural history. My favorite sources are early scientific texts that are totally poetic and bizarre and probably only exist in pairs. They’re more like folklore or passages from revelations. From a modern vantage I get this out-of-time sense that their authors are really not as sure as they sound, yet I’m amazed at how much they know almost entirely through observation. Maybe this is the tone through which we should understand all science. I think the best essays ring this way too—like a wide-eyed hypothesis.

BWR: And I have to ask, as someone so interested in spaces and their importance, where do you like to write?

SM: Yes, right. I have some problematic spatial issues but recognize that they are most often my writing brain hitting snooze. Writing in bed always works for me but makes it very difficult to sleep there afterwards. When I want to write I either sit in a bed, or put myself in a totally unfamiliar space in silence. I often work in libraries because there are so many weird options there, especially at old colleges, and because I like the company of hardcopies and all their strangeness as material. I’ll scrunch up in a study carrel or sit on the carpet between shelves of books. I think lots of writers are like this about process and beds and solitude and space, but I go for dark nooks and proximate text rather than sparseness and light. I write best when I feel like no one knows where I am.